Story

The Palace in Miniature

The Mineral Palace is long gone, but something of it remains—a glittering little reminder of the hopes and dreams of Pueblo.

A beloved local artifact returned to El Pueblo History Museum for a short time for the Mineral Palace exhibit which opened there in 2022. It’s humble in scale—about the same size as an old-fashioned hatbox—but it glitters in the light, and enchants the eye and the mind. Made of metals both common and precious, and studded with Colorado gemstones, its pillars and tiny windows hint at something larger than itself. Not just the original it’s modeled after, but a shared dream. A vision of the past and a hope for the future, crystallized into physical form.

It's a miniature of a building now long gone, one of the few remnants that proved it ever existed. And on the front, it reads in big bejeweled letters: “Pueblo, Colorado, Mineral Palace.”

The Mineral Palace and its miniature are, respectively, Pueblo’s history writ large and writ small. They captured an entire era, all of its hopes and dreams as well as its insanities. They embodied not just one but several periods of transition for Pueblo, as the city found its place in Colorado and the larger world. It may not have been everything Puebloans of the 1880s dared to dream, but it has its place in the sun—and, just like the jeweled miniature still on display today, it gleams all the more for it.

The tale of this entrancing object can be traced back over 130 years of Colorado history. It stands as a silent testament to a long bygone era, when Pueblo’s dreams ran wild, and free.

It began in the winter of 1890, when the energy in the Pueblo air was palpable. The whole town was abuzz. The newspapers had been crowing for weeks, reprinting a rallying cry being shouted across the country: the World’s Fair was coming to America.

Most of the major American cities were already competing for the honor of hosting the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Pueblo was not one of them, but even in Southern Colorado, the mood was electric. Everyone from politicians to shop sweepers had an opinion, a dream of what an American World’s Fair should look like. Most of Colorado was pulling for Chicago to host, as the youngest and most Western candidate.

And then, Pueblo’s Colorado Daily Chieftain reprinted a telegram one frigid February morning that was able to cut through the noise and make waves across the state, if only for its sheer audacity:

“The very mountains leap for Joy! Pueblo, the gateway to the mineral wealth of the Rocky Mountains, will redeem the promise made last December to duplicate the Colorado Mineral Palace […] in all its brilliancy and magnificent grandeur in Chicago in 1892!”

The Mineral Palace was a beautiful, incredible thing, of such grandeur and scale that it’s hard to imagine it was built in Pueblo. But it’s important to remember that at the time, in the 1880s and 1890s, Pueblo was an up-and-comer. It wasn’t that far behind Denver in terms of population, economics, and influence. As a railroad hub at a time when trains were the go-to method of travel for many Americans, countless people from all corners of the nation passed through town on a regular basis.

Pueblo was a new city. A bustling city. And its citizens were full of aspiration, ambition, and no little amount of determination.

Puebloans were already tired of living in Denver’s shadow, and eager to show their city’s worth. They had a shared dream of their city establishing itself as the premier population center in Colorado. This was part of the reason for Southern Colorado pulling so aggressively for Chicago to win the World’s Fair. Pueblo newspapers were already, by 1890, touting themselves as the “Chicago of Colorado.” They saw a future for themselves as the beating industrial heart of the Front Range, destined to eventually and entirely outgrow Denver just as Chicago had outshone Illinois’ own state capital of Springfield.

The Mineral Palace was by no means the only scheme intended to bring attention to Pueblo and make manifest its destined greatness, but it was undeniably the grandest.

“Grand” is, perhaps, not a strong enough word. “Dreamlike” might be better; it captures the ethereal beauty the architect and interior designer had put to page—and also the fever-dream of madcap scheming and manic flailing being done to get the thing built in the first place.

The Palace had been pitched in 1888 as a massive exhibition center, 300 feet long and over seven stories tall. The original plan was to construct it entirely of Colorado minerals, and to decorate it extensively with displays of the state’s mineral wealth, including gemstones encrusting the very walls and gold leaf coating the interior of the building’s twenty-one soaring domes. It was to have soaring columns, a shining marble facade, an indoor fountain, a full-size stage and seating space for thousands, electric lights, and the largest mineral collection in the world. The boldness and ambition of the project caught the attention, and the investments, of people all across the state. It was billed as a monument to the economic might and industrial future of Colorado, and it quickly captured the minds of thousands as a new and exciting symbol for the young state.

A lithograph, prepared for newspapers, based upon the original 1889 sketch of the Mineral Palace by architect Otto Bulow.

However, the Mineral Palace Company—which had been formed by prominent Coloradans to construct and manage the Palace—quickly realized it had bitten off more than it could chew. The Mineral Palace Company was overpromising and underfunded, and they knew it. The Palace was estimated to cost $150 thousand to build, and was expected to open by the end of 1889. But by February of 1890, when that daring telegram was reprinted in papers across the state, groundwork had barely begun.

The project was kept solvent by prayers and wishes and little else. At this time when the Company was proposing to build a whole second, duplicate Mineral Palace at Chicago, the original was still only a skeleton of lumber and scaffolding half a mile north of Pueblo’s downtown, and despite corner-cutting efforts at every turn it was already running over budget.

But despite these setbacks, the Company was led by a gaggle of ambitious schemers. In this new, national dream of a shining white city along the banks of Lake Michigan, they saw the perfect opportunity to boost the Mineral Palace and bring not just the nation, but the whole of the world, to Pueblo’s doorstep.

After Chicago was finally selected as the host of the World’s Fair in April 1890, the western states practically did leap for joy. Chicago was seen as a “Western” city at the time, one of the young and vibrant “us” aligned alongside Colorado against the big, greedy, old-money East Coast “them.”

A crowd crossing a bridge in front of the Administration Building at the World's Columbian Exposition, more popularly known as the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

For the next two years while the World’s Fair was being planned, the whole country was in an uproar. Ambitious, even insane, ideas were flung back and forth: towers literally miles high, a 700-mile toboggan run, moving sidewalks, captive hot air balloons, reconstructed Viking longships, imported structures from all over the world. Some thrived in the wildfire the country had become; others were burnt to a crisp by unfortunate realities like “budgets” and “impracticality” and “the laws of physics.”

So maybe it’s not so surprising at all that Colorado got caught up in this whirlwind of big, glittering, Gilded Age dreams.

When building a second Mineral Palace was proposed, it immediately caught the attention of Coloradans. Once news came from Pueblo that it had been pitched, newspapers in Aspen, Denver, Ouray, Leadville, and more began promoting it. For months, it was the end-all be-all idea for how to represent Colorado at the Fair.

It was perfect. Not only would it show the wealth of Colorado’s mines with its massive mineral exhibit, it would show the worthiness of Colorado’s cities. That such a grand structure could be built in Colorado—not in New York or Philadelphia or the District of Columbia, but in the fourteen-year-old frontier state—would show that Colorado not only stood on par with the other states of the Union, but in some ways had surpassed them. It would make all of Colorado’s greatest wishes come true, and the wealth would always and forever flow from the rich Rocky Mountain country!

An early photo of the Mineral Palace, likely taken before it opened.

That was the dream, at least, and it only continued to grow. Another idea which had sprouted wings was building an artificial mineshaft through which the World’s Fair visitors could walk and gain a sense of what it was like to see Colorado’s mineral wealth “in the wild.”

So why not combine the two? Newspapers began to boost the idea of a Chicago Mineral Palace with its grand hall and geology exhibit above ground, and the basement leading into a quarter-mile-deep artificial cave with real native gold ore glittering in the stone walls.

Never mind that the fairgrounds were on the shores of Lake Michigan, in a city so wet the water table is practically a foot above ground.

None of these ideas ever came to fruition. The ideas flooding into Chicago captured the imaginations of their home states, but not of the Fair organizers. The Fair had to operate within a tight budget (and also within the realm of reality) and its organizers were highly selective. But to accommodate the tide of pitches it was announced that each state would have a plot of land in the fairgrounds to construct a building to represent itself. But there was a catch: that state, not the World’s Fair board, would foot the bill.

Of course, many Coloradans’ first thought continued to be a Mineral Palace… until they looked seriously at how much it would cost. The state declined to pay for it, and few investors could be found.

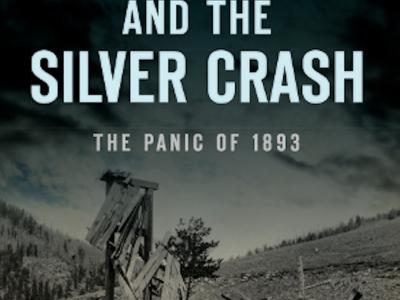

The sobering reality of Colorado’s economic state was echoed in the original Mineral Palace, which opened in Pueblo on July 4th, 1891 to great fanfare and much excitement. However, it was obviously not what had originally been envisioned. It was only two-thirds the size of the original design, both in length and height. There was no gold leaf on the domes, only copper, and no gemstones studding the walls. The marble facade never materialized, having been replaced with scrolled wood panels over brick walls. Inside the building was still almost a dream, an immense hall filled with all the splendor and beauty money could buy—but it was not carved of minerals. The effect was accomplished by humble paints and glazes.

Detail of the interior domes of the Mineral Palace, colorized, showing the intricacy of the interior design work, which was predominantly paint and sculpted wood instead of the planned precious metals and gemstones.

For a while the idea was floated to recreate this much humbler Palace in Chicago on an even smaller scale—half-size, suggested the Chieftain, and others even suggested quarter-sized. But even that was too extravagant for a state economy on the precipice of a silver market crash, just two years away.

Enter Luna Thatcher, Charles Otero, and the Board of Lady Managers.

The idea for a Women’s Building had been a part of the World’s Fair proposal since the very beginning. Many of the early lobbyists for hosting the fair in Chicago had been women—suffragists, artists, business women, and more—and their rallying cry was to have at the Fair an official place for women, not only in its planning, but in its execution. Two things came of that: the Board of Lady Managers, who would ensure that women’s contributions to American industry and culture would not be overlooked, and the Women’s Building, which would be dedicated entirely to the works of women in the sciences and the arts.

Notable women from around the country were invited to sit on the Board of Lady Managers. Among them was Pueblo’s own Luna Thatcher, wife of prominent Colorado banker Mahlon Thatcher. Thatcher was an enterprising woman and well-known in the state. When she heard that the Palace could not be replicated at the World’s Fair, she reached out to her fellow Lady Managers in Chicago with a proposal to kill two birds with one mineral.

The Board was planning a grand opening ceremony for the Women’s Building: Bertha Palmer, President of the Board, was to hammer in the final, golden nail with a solid gold hammer. In this ceremony Thatcher saw an opportunity.

She proposed that the receptacle to bring the nail and hammer to the ceremony would be no simple box, but something wondrous. Something glittering and beautiful, which would in and of itself be an artifact worthy of display. A work of art, encrusted with Colorado gemstones, depicting what was, at the time, Colorado’s newborn pride and joy: the Mineral Palace, in miniature.

The addition to the ceremony was approved, and Thatcher quickly set about making her plan a reality. She used her connections to raise the funds—entirely from donations by Colorado women—and hired a Pueblo jeweler named Charles Otero to design and construct the glittering Mineral Palace model.

Otero was at the time probably the premier jeweler and watchmaker in Pueblo, if not all of southern Colorado. He was also a man of many talents. He was a founding member of the Pueblo Baseball Association; he made eyeglasses and magnifying lenses as a side business; and he was an accomplished musician who played tuba for the Dodge City Cowboy Band.

With all this and more on his resume, he was more than equipped to bring Luna Thatcher’s glittering dream into reality.

In the end, the women of Colorado raised over $5 thousand (well over $160 thousand in 2022 dollars), and their money was well spent. Otero’s miniature was a work of art.

The facade of the Palace was almost perfectly represented on the miniature, from the dozens of pillars to the shining golden globes at each corner. And more, the lid lifted, revealing a fully decorated interior, with all twenty-one domes represented and the whole of it encrusted with gems. It even came complete with a tiny stage with a little clockwork mechanism showing a model donkey scaling Pike’s Peak—a miniscule copy of a much larger automaton featured in the real Palace.

This glittering little box was shipped to Chicago without much delay, and not long after its arrival the day came to inaugurate the Women’s Building.

This scale model of the Colorado Mineral Palace was created from minerals and gemstones by the Charles Otero Jewelry Company in Pueblo for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, where it was displayed along with Aspen's Silver Queen. This beloved artifact is on temporary loan from El Pueblo History Museum to the exhibit Zoom In: The Centennial State in 100 Objects at the History Colorado Center in Denver. One day soon it will return to its home at the museum in Pueblo.

The golden nail, donated by the women of Montana, and the golden hammer, donated by the women of Nebraska, were completely outshone in front of thousands of audience members by the box they arrived in: Pueblo’s Mineral Palace in miniature, provided by the women of Colorado.

After the final nail was driven home, the miniature was carefully placed in the halls of the Women’s Building, among all the other amazing works of art there. It was located on the second floor, on a balcony overlooking the main hall, and was viewed by hundreds of thousands of attendees at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, one of the most well-attended events in human history.

Every dream ends with a rude awakening. The glittering fantasyland of the World’s Fair and its White City came to an end in October of 1893. While it had left an outsized impact on American culture and brought the country into the limelight on an international stage, it had also barely broken even financially.

This was a sign of the times. The same year the World’s Fair opened was marred by the Panic of ’93, the worst economic depression in American history to that point. Stocks plummeted, prices skyrocketed, banks collapsed, and worst of all for Colorado, the silver market crumpled.

The state’s mining economy was devastated, and never truly recovered. The boomtown era, when seemingly anyone could strike it rich as a miner or entrepreneur, came crashing down around everyone’s ears. Visitors to the World’s Fair trudged home in an uneasy mood, to jobs they may not even have any more. So it’s no wonder that when Luna Thatcher’s glittering miniature was shipped back to its home state, it didn’t arrive to any fanfare.

For a while, it sat in a dark corner of the state capitol building’s basement, apparently forgotten. It took some rabble-rousing in Pueblo, headed by local newspapers like the Chieftain and the Star, to even arrange for its return.

The miniature fell back into Thatcher’s custody. Not even she seemed sure what to do with this expensive little thing. It was briefly offered up as a permanent exhibition at a proposed Women’s Museum in Chicago, but that museum was never built. Like many other projects of the time, it died on the vine, envisioned by Gilded Age minds but snuffed out by a new, harsher reality.

The time for childlike dreaming was over. Pueblo, along with the rest of Colorado and even the nation, had grown a little weary of ambitious projects and grand designs. Instead, most people tightened their belts and, in a much more practical mindset, returned to work.

The original Mineral Palace never attracted the attention or throngs of tourists its planners hoped for, but it remained an important piece of Colorado culture. It was saved from demolition in 1896 when it was purchased by the City of Pueblo, and was soon transformed into the centerpiece of a park. Separated from the overly ambitious dreamers who built it, the Palace became something much more practical.

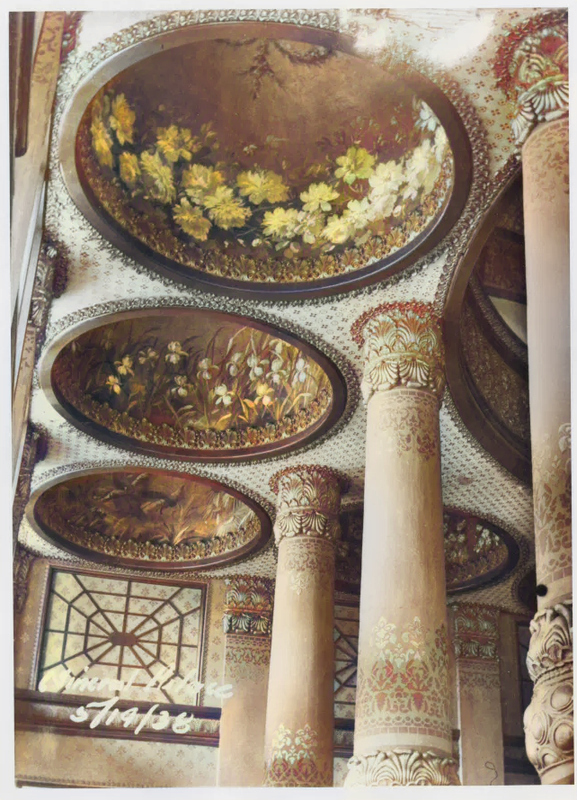

It was used as a gathering place, equal parts enormous museum and opulent community center. Its grand hall hosted countless civic events, political rallies, union meetings, private parties, and more. The Palace entered the twentieth century humbled, but still honored.

The miniature’s fate, meanwhile, remained in flux. For many years it remained with the Thatchers, only occasionally brought out for public display. Sometimes it was shown in Otero’s jewelry shop, sometimes at City Hall, and sometimes within the Mineral Palace itself—and what vertigo that must have caused. Imagine what it was like to lift the miniature’s gilded lid and gaze down into a tiny copy of the huge, glittering hall you were standing in, maybe even half-expecting to see a little doppelganger of yourself gazing back.

Eventually—it’s not clear when—the miniature fell into the custody of the city, which had already been the owner of the Mineral Palace since 1896. By the 1920s it was being displayed in City Hall, and it moved permanently to the Mineral Palace in 1927 as part of a reorganization by a new curator. And there the miniature stayed for several years, until the time came for it all to come crashing down.

Only fifty years after the Palace’s construction, its builders would have had a hard time recognizing Pueblo. The once-bustling, ambitious city had been struck hard over the last two decades.

First came the Great Flood in 1921, which destroyed much of the city center and left the city $30 million in debt. Then came the Great Depression. Pueblo was left reeling, struggling to make ends meet at every level, and there was simply no money for the upkeep of a huge, opulent, but ultimately unnecessary, Palace.

The Mineral Palace closed its doors to the public for the first time in 1935. While there were efforts to clean it up and even fundraisers to finance repairs, it was too little and too late. Despite opening for one last season in 1938, the Palace was closed again the following year and was demolished in 1942.

During this time period, much of the collection inside was seemingly lost. In truth very little remained, the rest was sold off for scrap. But the miniature was still in good shape, and, as far as many Puebloans at the time knew, it had simply vanished into thin air. It took some time for the full story of what happened to come out, and it was more the result of miscommunication than anything nefarious.

A professor from the Colorado School of Mines was the curator for the Mineral Palace in the 1930s. He oversaw the transfer of many of the minerals to the Mining Bureau, and had been present for the initial stages of demolition. And, under his oversight, the miniature had found its way to the collection of the School of Mines.

Examination of the Mineral Palace's many display cases, c. 1935-1938. When it opened, the Mineral Palace housed the largest and most complete collection of mineral samples in the world. Over time, many of the samples were given away or sold to cover costs of repairs.

The final days of the Mineral Palace were chaotic. Most likely, the miniature was transferred to the care of the School of Mines for safekeeping, away from vandals and workers looking for souvenirs. And, somewhere along the way, the people involved simply forgot to alert the public.

So the School of Mines knew they had the miniature, and assumed Pueblo knew as well. But in fact, almost nobody did. It wasn’t displayed, just kept in storage. It was available for viewing by request, but only if you knew to request it. Which, almost no one did. The end result was almost a decade of baffled Puebloans wondering what happened to Luna Thatcher’s marvelous miniature, until someone finally put two and two together and traveled up to Mines in 1953 to ask around.

Pueblo newspapers were filled with cheery surprise once word spread that the miniature was not only safe, but in near perfect condition and in very good hands. But they didn’t just want the satisfaction of knowing it was still around—they wanted it back.

At that time in 1954, El Pueblo History Museum had just opened across from the State Fairgrounds, and it was quickly deemed the perfect destination for the miniature. And so it returned to Pueblo, given over from the Mining Bureau to the State Historical Society and put on display at El Pueblo.

The rest is more or less history. The miniature was on display at El Pueblo History Museum from 1954 until 2017, when it was moved to the History Colorado Center in Denver. It had been on display there ever since as part of the exhibit Zoom In, until it recently returned to El Pueblo for the new exhibit on the Mineral Palace.