Story

You Should Have Seen It: Colorado Mineral Palace

In the Old Historic Northside of Pueblo, Colorado, there’s a park. It’s no longer the biggest park in the city—that ended thanks to interstate construction in the 1950s—but it has a strange mystique, a stately air reminiscent of a bygone era. This may confuse visitors, transplants, and even younger residents, but there are many in the city and beyond who still remember why Mineral Palace Park has its name.

In the late 1800s, the Gilded Age was in full swing, and Colorado was one of the gems of the nation. Beginning with the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, the state’s mines had produced vast fortunes in metals, minerals, and gemstones. Denver became a center of American high society, and mining magnates went from a few lucky claim-stakers to the nation’s nouveau riche. They were millionaires with riches to rival Rockefeller back east, and they were eager to show it off.

After all, it wasn’t called the Gilded Age for nothing.

The result was the Colorado Mineral Palace—a grand building a short walk north of downtown Pueblo, designed to show off Colorado’s mineral wealth as ostentatiously as possible. Multiple major figures of Colorado society became involved in its construction and operation, including former and future state governor Alva Adams, engineer and railroad magnate William Palmer, businessman and political activist William Hope Harvey, and others.

The Colorado Mineral Palace Company was founded to oversee financing and construction, which began in 1889. “The Colorado Mineral Palace at Pueblo, when completed, will be a dazzling object lesson to all the world of the ore-wealth of the Rocky Mountain region,” crowed the National Magazine that year. “The citizens of this prosperous, and in many ways remarkable city, are entitled to great credit for conception and execution.”

The company and its investors secured twenty-seven acres from the city for the project, for both the palace itself and expansive grounds. Local laborers and experts from around the country came together to dig a large lake, plant dozens of trees, install expansive flower gardens, construct a public bath house, and even built a small zoo—the second in Colorado.

The Mineral Palace Gardens included Lake Clara, which was named for Clara Latshaw who served on the first Park District Board of Commissioners and was instrumental in acquiring land for the park. The lake still exists, though it has been significantly reduced in size.

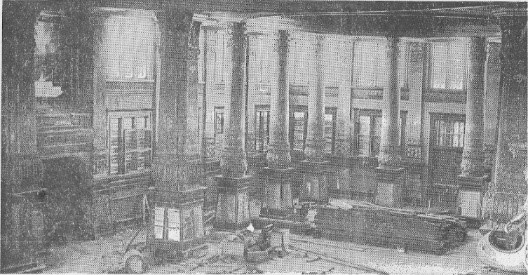

Swedish immigrant Otto Bulow designed the palace in a style inspired by the ancient Egyptians, with huge columns, towering statues, and twenty-one domes, the highest being over 70 feet above the floor of the main hall. The decor in the building was constructed from materials mined or quarried in Colorado, from the sandstone of the columns to the gold leaf and encrusted rubies lining the domes.

The building was at once museum and community center. At the foot of eight immense interior pillars were displays of every type of mineral imaginable, from gold ore and precious stones to more mundane sandstone, granite, and basalt, all mined in the Rocky Mountains. It even included some fossils that had been unearthed in the mines of Colorado. The city later added additional displays as well—for years, a section of the Old Monarch, a large tree that once soared over Pueblo’s Union street, was prominently displayed alongside the collected minerals.

But for most visitors, both from within the city and beyond, the main draw of the Palace was social. The building and its gardens were open to the public during the day, and many enjoyed strolls through the park, a swim in the lake, or reading a book in the cool of the massive stone building. For such a grandiose and even gaudy project, this was unprecedented.

Public celebrations were held frequently at the palace, which could accommodate over three thousand guests. This fourth of July celebration was held in or around 1910 and had a significant turnout.

“Aside from its attractiveness from an architectural point of view, Pueblo’s Mineral Palace commands attention from the beneficent purpose to which it is dedicated,” praised the Great Divide, a newspaper based in Denver. “Instead of being the glittering home of some papered favorite of fortune, or the fortified keep of some warlike noble, it [is] the abiding place of progress and the palace of industrious peace.”

At night, the palace was available for rent. For three decades, city residents held many of their grandest parties beneath its domes.

The main hall also featured a grand stage with a backdrop designed to resemble a grotto, inspired by the Cave of the Winds. The palace hosted many of the city’s performances, and the hall could accommodate an audience of over three thousand.

Flanking the stage were two statues who reigned over this strange and glittering domain. King Coal was donated by the coal mining companies of Trinidad, and constructed to look as if he was carved of coal. His consort and co-ruler was the Silver Queen, donated by the city of Aspen and its silver magnates. She was shimmering silver and decorated with crystals and gemstones, and made a visit to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

In its heyday, the stage at the Mineral Palace was flanked by King Coal and the Silver Queen. The fate of both statues is unknown, but they were likely dismantled and sold to cover the palace’s upkeep debts.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the grandiosity of the building and the ambition of its developers, from the very beginning it faced financial troubles.

The Colorado Mineral Palace Company raised over $100,000 for its construction, but in the end the project took a year longer than expected and went $50,000 over budget—an astronomical sum at the time, resulting in a total cost equivalent to $4.3 million in 2020. Shortly after construction was complete, the company filed for bankruptcy and was forced to turn over the property to the city of Pueblo.

Then came the Panic of 1893, a serious economic depression followed shortly by the crash of the silver market. Colorado’s mining economy suffered greatly, including all the mining magnates who’d financed the Mineral Palace.

Even in the palace’s heyday the city struggled to maintain it. Repairs were both frequent and expensive, and the building had no heating at all—a cost-saving measure that made it almost unusable for half the year due to cold or windy weather.

And then, barely three decades after the Palace's grand opening, the Great Depression came.

This scale model of the Colorado Mineral Palace was created from minerals and gemstones by the Charles Otero Jewelry Company in Pueblo for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, where it was displayed along with Aspen's Silver Queen. This beloved artifact is on temporary loan from El Pueblo History Museum to the exhibit Zoom In: The Centennial State in 100 Objects at the History Colorado Center in Denver. One day soon it will return to its home at the museum in Pueblo.

The building and gardens quickly went from costly to impossible to maintain. The park’s lake was almost impossible to keep filled, and eventually the city was forced to drain it entirely in order to coat the bottoms and sides with rock and concrete to prevent future leaks. This alone was an enormous expense and was only possible because of the generosity of two local stone quarries and assistance from Depression-era federal work programs.

While funds were raised to tend the grounds, the Mineral Palace itself lay almost untouched and increasingly decrepit. It finally closed to the public in 1935, and the city made much-needed repairs. The palace reopened in 1938, but only for a year or less. By the summer of 1939 the building was closed again.

For years the fate of the palace was uncertain, and world events quickly disrupted any possible plans. With the outbreak of World War II at the end of the decade funds were redirected away from leisure towards more important functions. And when the United States joined the war effort in 1941, the focus of Pueblo was not on the Mineral Palace—it was on the steel mill and the army depot.

And so, the Mineral Palace continued to crumble until, finally, by 1943 city leaders announced that everything within the building would be sold off to contribute to the war effort, and the structure would be demolished.

There’s a bit of mystery surrounding the final years of Mineral Palace. It’s unclear how much remained of its riches by this point, but the city sold off whatever was left—including King Coal and the Silver Queen. And only a short while later, the building itself was torn down.

Maybe the moral of this story is cautious spending, or humility. Such an enormous expense, all for showing off the wealth of Colorado’s mines to the world, would be hard to justify today. But that’s not really the legacy of the Colorado Mineral Palace in Pueblo.

Over the years, the park shrank as large swaths were paved over by the interstate. But remnants of the Mineral Palace remain—in the lake and its pavilion, in the crooked sandstone walkways and the great iron arch over Main Street, in the flower beds and the pine trees. But most of all, it lives on in the memories of Puebloans, many of whom still recall stories from their grandparents who saw the palace in its heyday, who walked and danced beneath its soaring domes and glittering pillars.

One of the earliest known photos of the palace, taken by famed photographer William Henry Jackson between July and September, 1891. Notice the gilded columns with mineral displays at the base, and the people freely socializing at benches and tables. The Colorado Mineral Palace stood for only 52 years.

Sources

Fredrick, Larry. “The Aspen Silver Queen Story.” Aspen Historical Society, 2019.

Letts, C. A. “Pueblo’s Parks.” Official Souvenir Book. Denver: Press of the Rocky Mountain Bank Note Company, 1910.

Manchester, D. W. “The Colorado Mineral Palace at Pueblo.” The National Magazine, November 1889.

Ochs, Milton B. The Heart of the Rockies: Illustrated, as Reached by the Pike’s Peak Route. Cincinnati: The A. H. Pugh Printing Company, 1890.

Talbot, Ray H. “Municipal Stone Quarries Aid City Parks.” American City, July 1939.

More from The Colorado Magazine

1904: The Most Corrupt Election in Colorado History Between stuffed ballot boxes, election clerks hopping off trains, and three governors in a day, Devin Flores might just have a point.

Historic Hardware May Help Fight COVID-19 As a preservationist working from home in a 1930s Art Deco apartment building, I have often lamented the fact that so much historic door hardware has been painted over, forever dulling the lovely details that add character and art to our everyday lives. I don’t consider myself an artistic person, so my interest in these seemingly basic details relates to my appreciation of what seems like unattainable creativity on my part.

Trinidad’s Temple Aaron Looks to the Past to Secure Its Future In the spirit of renewal and perseverance, the people of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico have joined together to ensure a future for Trinidad’s Temple Aaron.