Story

Stolen Votes and Silenced Voices

More than 100 years ago, an unflattering political cartoon in The Rocky Mountain News tested the limits of the First Amendment and Americans' confidence in their elections.

Men working with type on rollers in the printing room of the Rocky Mountain News, 1900s-1910s.

Like many Coloradans in the aftermath of disputed elections in 1904, Thomas Patterson was thoroughly fed up with the state’s political system. While there wasn’t much he could do about it, he was the publisher of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News and could at least make his voice heard. So, on June 25, 1905, he printed a remarkably biting cartoon on the front page of his newspaper.

The cartoon was captioned “The Great Judicial Slaughter House and Mausoleum,” and it depicted five justices on the Colorado Supreme Court beheading Democratic officials. In a particularly personal touch, it singled out Chief Justice William Gabbert as “The Lord High Executioner” because of his role in enabling Republicans to throw out election returns. Just in case the message wasn’t obvious, the News ran a banner headline across the top of page one, proclaiming, “If the Republican Party has overlooked anything from the Supreme Court it will now please proceed to ask for it.”

Colorado Supreme Court justices were outraged by the front page of the Denver Rocky Mountain News on June 25, 1905, which among other inflammatory content featured this political cartoon depicting them as a board of executioners.

The cartoon, along with a parade of articles over the following few days assailing the state’s highest court, launched one of the more significant free speech cases in US history. Patterson knew he could face prosecution because the First Amendment at the time failed to protect publishers and editors who criticized judges. But the publisher—a pugnacious Democrat who was also serving a term in the US Senate—believed newspapers had the right to take on those in power as long as they printed the truth.

The ensuing case, Patterson v. Colorado, would eventually wind up in the US Supreme Court. It would have national ramifications the following decade, influencing legal battles over free speech that erupted when the federal government cracked down on civil liberties during World War I.

A Disputed Election

Patterson’s outrage at Colorado’s political leaders stemmed from the election for governor in 1904. It was a time of widespread violence in the state’s gold and coal mines, and Republican incumbent Governor James A. Peabody drew support from corporate leaders because he repeatedly invoked martial law to crush union activity. The initial ballot count, however, seemed to show that the pro-labor Democratic challenger, Alva Adams, won by about 10,000 votes. Democrats across the state were ecstatic. “Colorado repudiates Peabodyism and Militarism,” blared an all-caps headline in Boulder’s Daily Camera on the day after the election.

Rocky Mountain News employees at work in the newspaper's art office, January 1902.

But the celebrations proved premature. Reports of widespread election fraud soon circulated. As disputes broke out over how to tally the votes, Peabody and his business allies held two ace cards: a sympathetic Colorado Supreme Court and a Republican-dominated State Board of Canvassers. Both produced critical rulings in the weeks after Election Day that overturned apparent Democratic victories in state legislative races and handed complete control of the Colorado General Assembly to Republicans. Patterson fumed. The Rocky Mountain News assailed Republicans for engaging in a blatant attempt to steal the election, alleging that “step by step the conspirators have boldly and ruthlessly pressed toward their goal until nothing remains but the actual consummation of the crime.”

Undeterred, the General Assembly launched an investigation into allegations of ballot tampering. After uncovering evidence of substantial fraud by both parties, state legislators decided that neither Peabody nor Adams could be declared the victor. Instead, they unexpectedly tapped the Republican lieutenant governor, Jesse McDonald, to be governor. (The high-stakes negotiations gave Colorado the distinction of technically having three governors in one day: Adams, Peabody, and McDonald.)

Thomas Patterson, publisher of the Denver Rocky Mountain News, was cited for contempt for criticizing the Colorado Supreme Court.

Democrats got more bad news when the Colorado Supreme Court subsequently threw out the results of local elections in Denver. This enabled Republicans to take over political offices that had been occupied by Democrats, all of which proved too much for Patterson. The Rocky Mountain News as well as Patterson’s other newspaper, the Denver Times, ran one article after another lambasting the justices and suggesting they were under the thumb of corporate interests, including utilities that wanted to extend lucrative franchise agreements with Denver, as well as railroads and mining operations trying to win legal battles against their labor opponents.

When two competing Denver newspapers editorialized that Patterson should be fined or imprisoned for his attacks on the judiciary, the publisher responded with a ringing defense of press freedom. Essentially daring the justices to come after him, Patterson proclaimed in a Denver Times column that the newspaper “can as well be edited with its editor behind the bars.”

A Publisher in Contempt

Less than a week after Patterson’s newspapers began aiming their fire at the justices, Colorado Attorney General Nathan Miller filed a motion with the court asking that it find the publisher in contempt. Miller argued that the cartoon and articles, which he inserted into his motion, threatened to “impede and corrupt the due administration of justice.”

Patterson deftly retaliated by publishing Miller’s motion in the Rocky Mountain News, thereby reprinting the very materials that Miller found objectionable. But the justices were not amused. Within hours of receiving the attorney general’s motion, they served Patterson with a citation and scheduled a hearing to determine whether the publisher should be held in contempt.

Patterson was a lawyer, and he knew he faced long odds. The Colorado Supreme Court had repeatedly charged newspaper publishers and editors with contempt for criticizing judicial proceedings on the ground that such press coverage could interfere with the administration of justice. Less than a decade prior to Patterson’s case, the court had upheld a prison sentence against a newspaper publisher for writing a series of articles attacking a local judge. In a case against another publisher, the justices declared, “It is a public wrong—a crime against the state—to undertake by libel or slander to impair confidence in the administration of justice.”

Nevertheless, Patterson’s lawyers argued that the Colorado Constitution gave newspapers full license to criticize government officials as long as they printed the truth. And the publisher’s brief, like a good investigative article, also exposed the underhanded and corrupt efforts to overturn the gubernatorial election and the elections of local Denver officials.

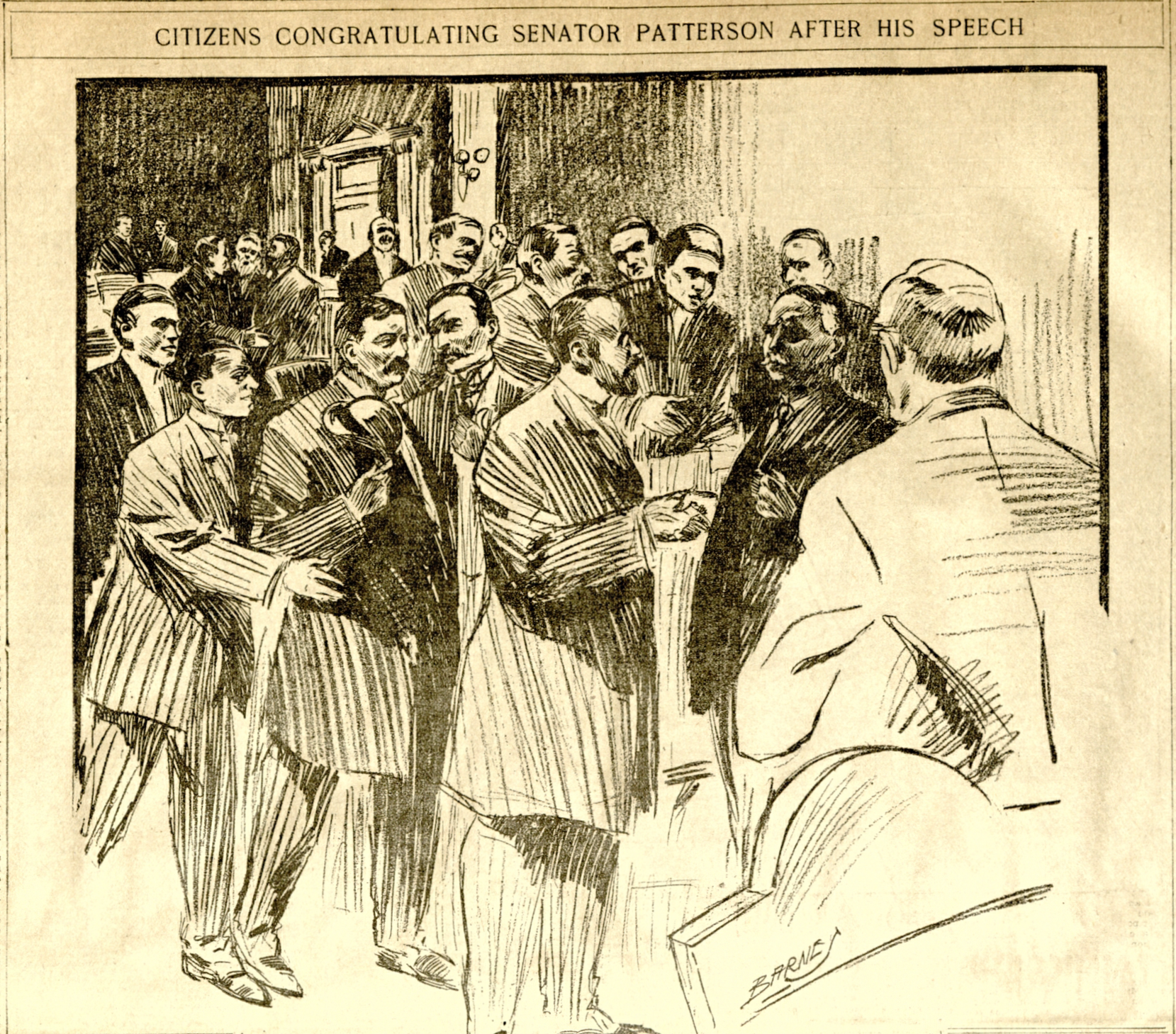

Spectators congratulated Thomas Patterson after he defended himself before the Colorado Supreme Court.

The brief alleged that corporate agents had funneled hundreds of thousands of dollars to Peabody’s campaign. The agents had also set up secret negotiations between Colorado Supreme Court justices and Peabody over nominating two new justices to the court right before the governor left office. Railroad representatives went so far as to take a carriage after midnight to the house of one of the nominees and confer with him for about two hours before signing off on legislative confirmation. As for the court’s decision to overturn the Denver elections, Patterson’s brief warned that it would potentially undercut home rule in Denver and block voters from deciding whether to renew the franchises of local utilities.

Patterson’s newspapers, in the view of his lawyers, had done nothing more than to print the facts. “To state the truth,” the brief concluded, “is not and cannot be a criminal contempt of this honorable court.”

On the morning of November 28, 1905, the Colorado Supreme Court held a hearing into the matter, giving each side one hour to argue its case. The courtroom was so packed with state and local political officials, business executives, and labor leaders that many spectators had to stand even after bailiffs brought in extra chairs. Despite the drama, the justices needed little time to reach a decision. On the following afternoon, Chief Justice Gabbert announced that Patterson was guilty of criminal contempt. He fined the publisher $1,000—no small sum at a time when an average worker’s weekly earnings amounted to little more than $11.

Far from being chastened, however, Patterson told the court that he had an obligation to print the truth. He pledged to appeal his case to the US Supreme Court. When the justices filed out, the publisher found himself receiving effusive praise in the courtroom, with many spectators—including politicians in both parties, as well as the reporters covering the hearing—lining up to shake his hand. Coloradans and residents of other states wrote Patterson by the hundreds to laud his stand against the court, with their letters quoted prominently in the Rocky Mountain News. “It is a hopeful sign that there are still men of influence and ability who are willing to risk imprisonment and other humiliation in exposure of official Infamy,” wrote one resident of Cripple Creek.

Despite such enthusiasm, Patterson’s odds before the US Supreme Court seemed no better than in the state court. The nation’s highest tribunal had rarely weighed in on First Amendment cases and never directly addressed the question of whether a newspaper could be penalized for factual content. But the justices had made it clear that they favored restrictions on harmful speech. Just a few years before the Patterson case, the Court had upheld the deportation of an English-born anarchist who planned a series of speeches calling for a general strike. The government, Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote in that case, had the right to exercise its “power of self-preservation.”

Patterson appeared before the US Supreme Court in March 1907 to argue his case in person. He contended that no one could be punished in the United States for telling the truth, and he warned that a republican form of government could not exist if newspapers were prohibited from publishing the facts. Two representatives from the Colorado Attorney General’s office focused on a single argument: the case was purely a state matter and not one in which the federal courts had jurisdiction.

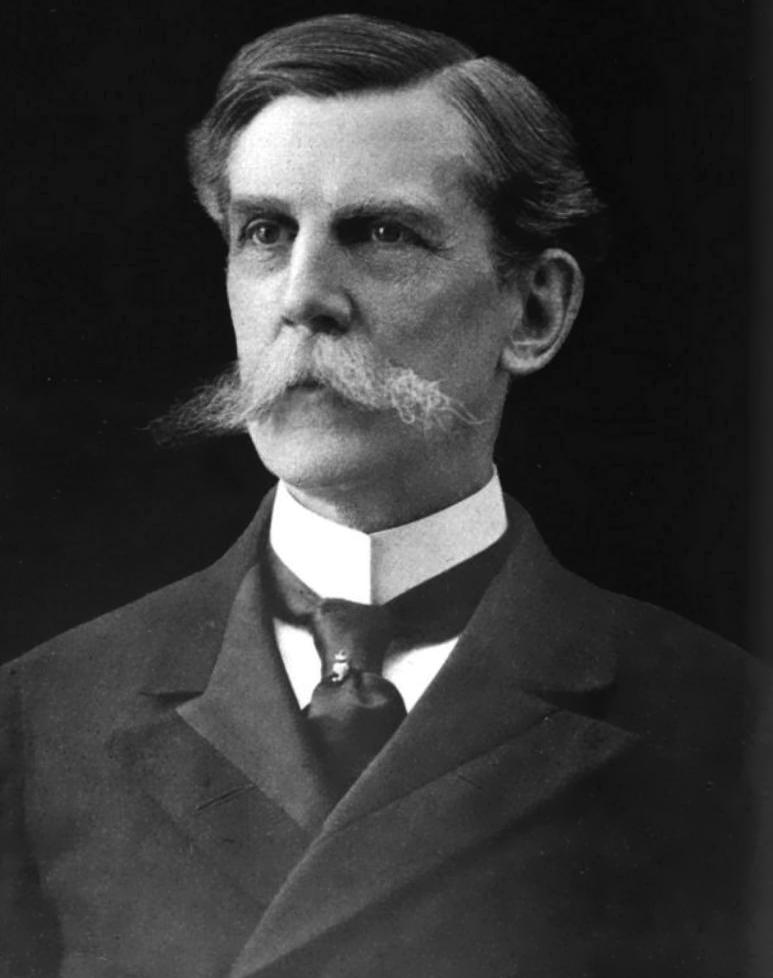

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote the majority opinion in Patterson v. Colorado. 1902.

The court readily disposed of Patterson v. Colorado, issuing its seven-to-two ruling a little more than a month after it had heard the argument. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., in an opinion that ran to fewer than a dozen paragraphs, agreed with the Colorado Attorney General’s office that this was a state matter and not one for the federal courts to decide. This wasn’t surprising—according to legal thinkers of the time, the First Amendment protected citizens from sanctions by the federal government. It wasn’t for several more years that the Supreme Court began ruling that it applied also to state and local governments. But Justice Holmes went one step further, taking issue with Patterson’s claim that he had the right to publish the truth. Drawing on legal precedents from eighteenth century England, Holmes concluded that constitutional press protections primarily meant that the government could not stop a newspaper before it went to press. Once an article was published, however, the government could punish the newspaper for printing material deemed contrary to the public welfare.

For Patterson, the ruling marked the end of his legal journey. He lobbed one final broadside in the Rocky Mountain News, writing, “I am not now and never will be ashamed of printing only the truth about public officials, whether they be judges or governors or legislatures. The truth only offends those whom it hurts.” He then paid his $1,000 fine, plus another $424.40 in court costs, stepped back from the legal fray, and died less than a decade later. But the Supreme Court ruling had established a precedent for weak press protections and the case of Patterson v. Colorado would help enable a historic crackdown on free speech.

Prosecution of Anti-War Dissidents

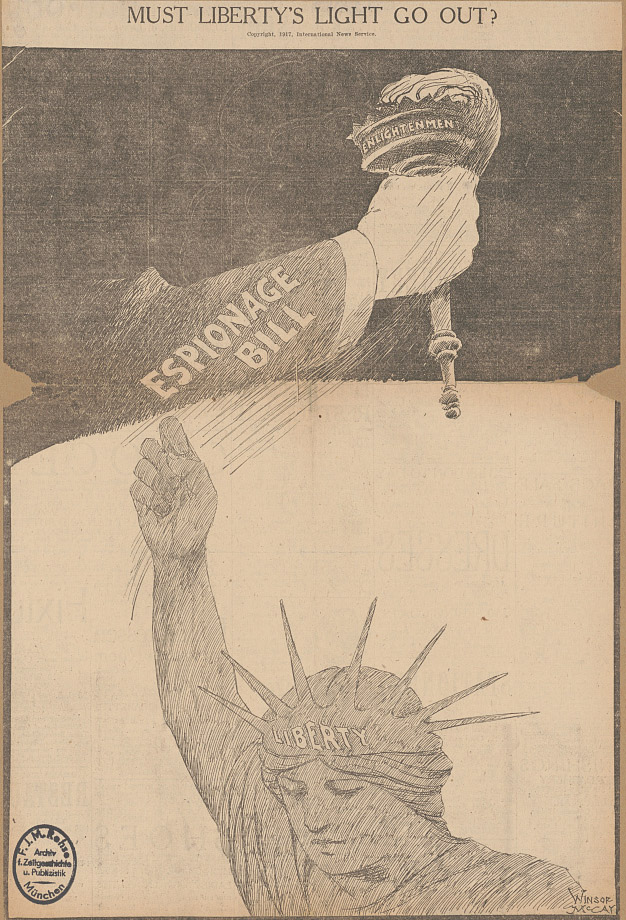

The early years of the twentieth century represent a low point in First Amendment protections, and Patterson v. Colorado was one of many court cases that, from our modern point of view, produced alarming rulings limiting Americans’ right to free speech. A decade after Patterson argued his case before the Supreme Court, the United States entered World War I in 1917, and President Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act making it illegal to denounce the war effort. Among the many people ensnared by that law was a Denver resident, Perley Doe, who had moved from Boston to get treatment for tuberculosis. But instead of regaining his health, he became the first person in Colorado to be prosecuted for speaking out against the nation’s involvement in World War I. His crime: mailing letters to professors, ministers, and officials in Washington, DC, that questioned whether the war was justified.

The Committee for Public Information worked to whip up support for World War I with propaganda pieces such as this pro-war poster.

Doe was convicted in Denver’s federal court in February 1918 and sentenced to fifteen months in prison. After the clerk of the court read the guilty verdicts, the ailing man tottered out of the courtroom, supported by his wife, and fainted just outside the courtroom door. A number of spectators, including members of the jury that had just convicted him, rushed to his aid. When Doe regained consciousness, he became hysterical. “How can twelve men agree on such a verdict?” he asked.

Doe was one of more than 2,000 people who faced prosecution for opposing the war. They included such public figures as Eugene V. Debs, a socialist who had run for president four times, as well as a number of lesser-known people who merely happened to voice impolitic opinions. In one particularly infamous case, prosecutors won a ten-year prison sentence against a Hollywood producer, Robert Goldstein, whose only crime was promoting a movie about the American Revolution that portrayed British Redcoats in an unflattering light. This, prosecutors contended, was illegal when the current-day British were important World War I allies.

The wartime fervor became so intense that it cut short the career of one of Patterson's proteges. Edward Keating had worked as managing editor of the Rocky Mountain News before winning election to Congress. But when he voted against declaring war on Germany, his Colorado constituents voted him out of office.

But another former News editor, George Creel, saw his career take off during World War I. He headed up the Committee on Public Information, a national propaganda office created by Wilson to rally Americans behind the war. The office dispatched tens of thousands of “four-minute men” to movie theaters, churches, schools, and labor halls to give four-minute speeches promoting the war effort while launching incendiary attacks on anyone who questioned the war.

The 1917 Espionage Act raised concerns about a crackdown on basic liberties, as shown in this political cartoon.

In such a charged atmosphere, federal judges and juries found it virtually impossible to acquit those charged with disloyalty. Several judges cited Patterson v. Colorado among other precedents in upholding the Wilson administration’s restrictions on free speech. When the first Espionage Act cases reached the US Supreme Court in early 1919, Holmes wrote a trio of opinions that sided with prosecutors. Although his legal reasoning began to edge away from his ruling in the Patterson case, Holmes maintained his view that the First Amendment offered only limited protection to those speaking out against government policies.

But in late 1919, a year after the end of the war, Holmes had a notable change of heart. In a case involving four Russian-Jewish immigrants who opposed Wilson’s policies, the justice mounted a ringing defense of the importance of freedom of speech. He likened free expression to a marketplace in which it was essential to allow ideas to compete for acceptance. “We should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe” unless they present an imminent threat to the country, he wrote.

Holmes failed to persuade a majority of his brethren, who upheld the Espionage Act convictions. Over time, however, his expansive view of the First Amendment would gain wide acceptance, leading to our modern understanding of free speech. The Supreme Court eventually determined that newspapers could criticize the courts and enjoy broad protection against reprisal. The justices even gave constitutional protection to the most objectionable and hateful speech.

In recent years, Colorado has again found itself on the front lines of the nation’s free speech battles—though the disputes, involving gay marriage, would be unrecognizable to Patterson. The US Supreme Court in 2018, in a controversial ruling, sided with a Lakewood baker who cited the First Amendment in refusing to create a custom wedding cake celebrating the marriage of a gay couple. Earlier this year, the justices again took an expansive view of the First Amendment, backing a Denver-area graphic designer who claimed that freedom of speech gave her the right to refuse to create websites for a same-sex couple.

Patterson v. Colorado has long been superseded by more forward-looking interpretations of free speech. But as demonstrated by the latest cases involving same-sex couples, the legal appeals by Colorado residents continue to shape the nation’s understanding of the First Amendment.