Story

“Once a Savage, Always a Savage” - Indigenous Mascots in Small Communities

Flipping through the old yearbooks from rural Colorado reveals a harrowing history of misrepresentation and appropriation, but also an underlying current of small towns fighting to create a shared identity.

Editor's note: This article was adapted by the author for The Colorado Magazine from an essay submitted to the Emerging Historians Contest.

As the wooden floor trembled, two enemy groups paced back and forth, sneering at their opponents. One group sported all-purple attire, while the other wore scarlet, blending in with the raucous sea of onlookers surrounding them. An irrepressible storm of stomps, claps, and shouts ricocheted across the room. Overlooking it all was a wall bearing a single phrase: “The Pit.” Once the mob’s excitement reached a fever pitch, three men in stripes emerged onto the court and blew into their whistles. The high-school basketball game between the Sedgwick County Cougars and the Yuma Indians had begun.

Before 2021, this was not only a recurring experience in Yuma, Colorado, but a key thread in the agrarian community’s social fabric. The town championed a caricatured Indigenous mascot for decades, plastering Yuma Indian imagery on apparel, car bumpers, and local businesses—and they were not alone. Almost two thousand school districts across the United States used Native-themed mascots in 2021, including other Colorado schools such as Lamar and Arickaree. These caricatures, and the ways communities identify with them, influence how countless Coloradans view the history of their communities, and of American violence against Plains Natives. And although eastern Colorado’s howling winds buried yesteryear’s arrowheads and bullet casings, these histories and how people interact with them continue to resonate strongly in both Native and non-Native communities. After all, the graves of Beecher Island, a battlefield where the US Army engaged the Cheyenne and Arapaho in the aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre, lie only thirty miles from The Pit at Yuma High School.

Indigenous mascots have been a topic of debate for many decades, and in recent years the issue has escalated to national prominence. The former Cleveland Indians and the Washington Redskins have changed their mascots (to the Guardians and the Commanders, respectively). Here in Colorado, Strasburg and Arapahoe High Schools negotiated with Wind River’s Northern Arapaho, becoming the only Colorado districts with ongoing tribal agreements to maintain their Native mascots.

The story is different for small towns like Yuma, Lamar, and Arickaree. All three of these communities had Indigenous mascots in the recent past, and each benefited socially from the tight-knit bonds of loyalty facilitated by their Indigenous-themed high-school teams. This is epitomized by banners in Lamar reading “Once a Savage, Always a Savage,” and rowdy games at The Pit, which were not just a spectacle but also a means of uniting the community. Indigenous school mascots not only contributed to building these social bonds, they also played a role in conditioning the remembrance of historical violence against the peoples they erroneously depicted. These caricatured mascots distorted the history of the Eastern Plains and their gradual removal continues to impact the communities that sported them.

The Yuma Indians of Yuma County

The town of Yuma curiously shares a name with the Yuma or Quechan, an Indigenous people whose homeland lies a thousand miles away in Arizona and California. It’s unknown how the name came to be in Colorado, but in 1935 Harold Andersen (at the time an amateur archaeologist, though he would later earn a doctorate) led the charge for Yuma High to adopt the “Indians” as a mascot. He created a new logo which depicted an Indigenous man in a headdress triumphantly gazing upward on a “Yuma Point.”

Dr. Andersen’s original 1935 Yuma Indians logo, complete with a Yuma Point.

Like many other contemporary sports icons, this new logo was reductive. Its highlight of headdresses and weapons emphasized a “warlike” depiction of Indigenous peoples as a shorthand for a sports team’s pursuit of victory. Some time later the logo was changed again. A red Y (for Yuma) replaced the arrowhead, leaving only a generalized Indigenous likeness indistinguishable from thousands of others.

The history of interactions between Anglo-American settlers and the Indigenous peoples of Yuma County extends far beyond the projectiles locals found scattered throughout the sandhills. The town of Yuma lies near the sites of a series of retaliatory raids carried out by the Cheyenne and Arapaho following the Sand Creek Massacre. Violence in the region reached a climax in 1868 when white volunteer scouts mobilized an offensive against Cheyenne and Arapaho in present-day Yuma County. The tribes pinned the unit along an Arickaree River sandbar where the scouts repelled numerous assaults before the Cheyenne and Arapaho withdrew.

For well over a century, Yuma County has hosted an annual Battle of Beecher Island celebration canonizing the volunteers as victimized champions of an idealized American West. The 1905 celebration opened with remarks from Rev. C.A. Brooks, who reiterated the necessity of violence against “cruel savages, who knew no mercy, and fairly reveled in their rapine and butchery.” At the 1930 celebration, event organizers distributed the Beecher Island Annual, which noted that locals “keep alive the memory of a noble band of scouts and frontiersmen” and maligned the “aboriginal savage,” whom frontiersmen fended off in a “heroic struggle against overwhelming odds.”

Since the late 1970s Yuma middle schoolers have gone on field trips to Beecher Island. A 1985 Yuma Pioneer piece suggested the excursion fit into a “study of Early Peoples of the Americas,” implicitly marking the Cheyenne and Arapaho as identities of the past, not still-living communities. On these trips, students scanned deserted locations like the offensively named “Squaw Hill Monument” and reconstructed regional maps devoid of Indigenous voices.

It is impossible to untether Indigenous history from Yuma. Even the town’s name speaks to how white settlers of the region perceived Native Americans. The “Yuma Indians,” and their logo, have roots in a reductive representation of Plains peoples, and speak to a lack of awareness of Indigenous history both past and present, and a failure to involve the descendants of the original inhabitants of Yuma County in local education and culture.

A 2016 student banner demonstrating Lamar’s commitment to their Savage identity.

The Lamar Savages of Prowers County

In an old yearbook photo, nine high school seniors posed for both the camera and posterity. The mullets, Los Angeles Raiders shirt, and Aqua Net are all dead giveaways that this was taken in 1987. But behind the students is a seemingly more anachronistic sight: a painting of unoccupied tipis scattered along the sandbanks of a winding creek. While observers at the time admired the “autumn Indian village” depicted by these seniors as “Savage Art” to show their school pride, those perusing the ’87 Chieftain today cannot ignore the painting’s dissonance with local history.

About an hour’s drive from Lamar lies the site of the Sand Creek Massacre, where a peaceful encampment of Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho was attacked by the Third Colorado Cavalry in late autumn, 1864. More than 200 unarmed civilians, the majority of whom were women and children, were indiscriminately butchered even as their leaders waved American flags and attempted to surrender. Did these Prowers County seniors contemplate this episode of their history while creating their “Savage Art,” which so eerily resembles the site of Sand Creek?

1987 Lamar seniors pose with their shared painting of a river, invoking memories of Sand Creek.

With this tragedy so relevant, the adoption of the “Savage” as the mascot of Lamar High School takes on an even more troubling nature than other Indigenous mascots. Coloradans who defend the Sand Creek Massacre have a history of referring to Sand Creek victims as “savages,” including Governor John Evans, who in 1864 guaranteed safety for the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho before ordering the attack. The imagery of the “Lamar Savage” does nothing to address any of this. Instead, it is another caricature of an Indigenous man, almost indistinguishable from Yuma’s mascot.

This insensitive and even dismissive attitude towards Indigenous history can be found across old issues of Savage Chieftain, Lamar High’s student newspaper. The 1948 edition portrayed a sketch of a tipi unfurling to reveal a photograph of Lamar High titled “The Big Tepee.” A graduating senior’s poem follows:

Heap big doings in Savage Nation,

All tribes gather in Big Tepee.

Many scalps won! Big celebration!

Heap big Pow-wow, fine to see.

Great Medicine Men got heap big mess,

Teach young braves to follow trail,

Seniors blaze through wilderness.

This poem is astonishingly discriminatory by modern standards, and typecasts Plains Natives as fanatical scalpers in order to mirror Lamar’s enthusiasm for high school sports. However, being a Lamar Savage incorporated not only athletic excellence but the entire educational experience. Another page sketched a “Freshmen Papoose” as an Indigenous infant with a single feather and “Senior Warriors” as headdress-wearing adults. Progressing through Lamar High’s ranks meant roleplaying a cartoonish and reductive portrayal of Indigenous peoples. These attitudes were still present fifty-three years later in 2001, when Lamar freshmen underwent an initiation ceremony which offensively required girls to dress as “Indian braves” and boys as “Indian squaws.” The Chieftain preserves alumni’s Savage days by fastening nostalgic memories to a caricatured representation of the peoples whose lands the Lamar Savages occupy.

Sketches in the 1948 Chieftain detail Lamar students’ progression using stereotyped Indigenous social positions.

For generations, Lamar students personified a “Savage Spirit” that the 1989 yearbook declared “never dies.”

In yearbooks from the 1960s, male athletes are consistently referred to as “Savages” and female students as “Savagettes,” cheerleaders who generated “support, loyalty, and enthusiasm.” One 1975 Yuma Pioneer article had similarly identified female athletes by the slur “squaws,” since “we all carry the mascot of ‘Indians,’ no one said it was just for boys!”

Over the years, the Chieftain also highlighted objects such as the school totem pole (a cultural construction associated with the Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest, over a thousand miles from Lamar), and a “Savage Siege” parade float with a limp coachman aboard a ransacked wagon, stereotyping Plains peoples as pillagers and bandits.

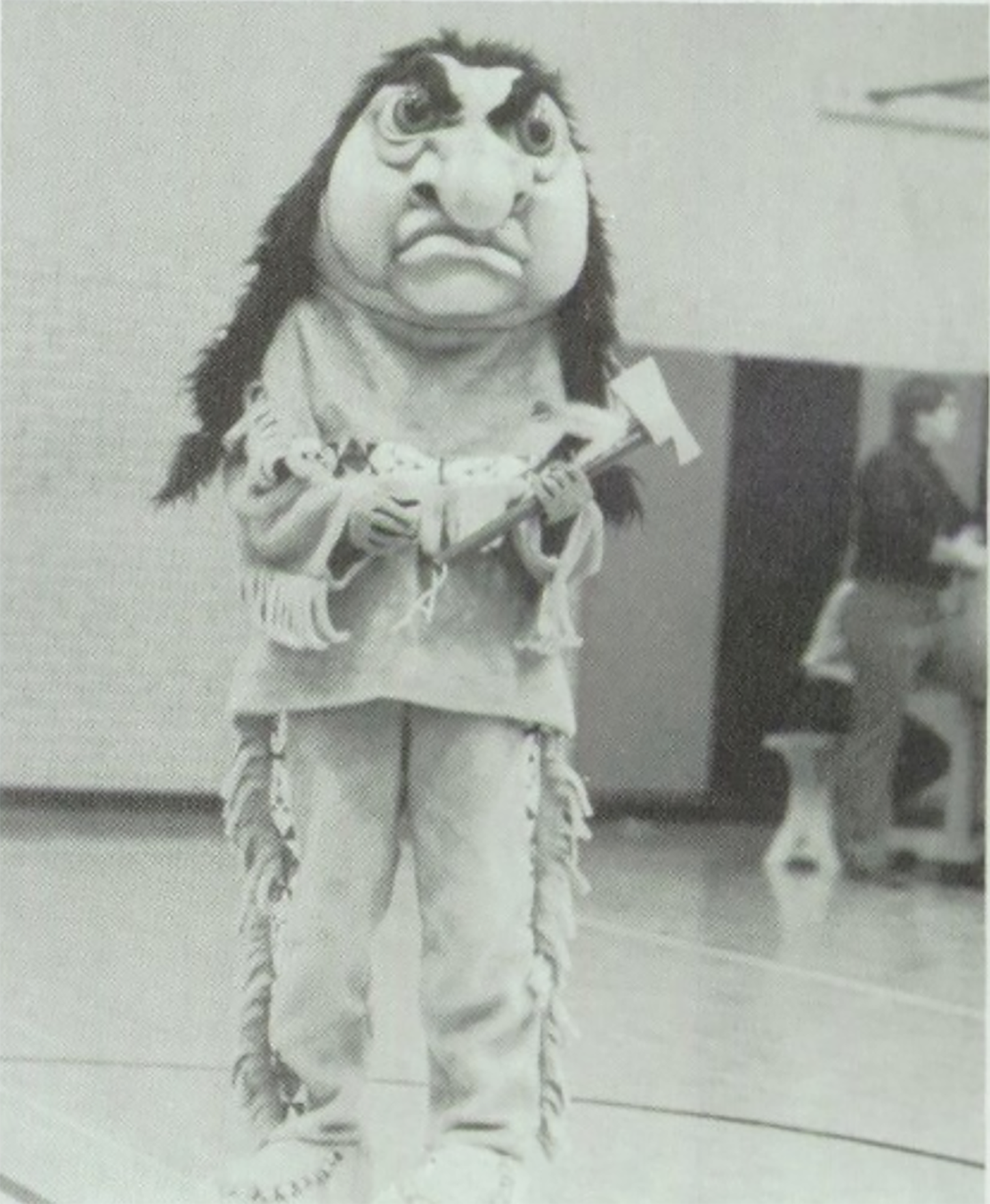

A 1986 initiative to “revive Lamar High School spirit” introduced a new costumed mascot: a wide-eyed, bulbous-nosed, tomahawk-wielding Indigenous caricature named “Chief Ugh-Lee.” At games across the state, Chief Ugh-Lee applauded opponent misses and cursed their scored baskets, providing an interactive exchange with a costumed embodiment of Lamar’s “Savage Spirit.”

While it can be haunting to flip through pictures of Chief Ugh-Lee mimicking a scalping, students of the time generally saw their “Savage Pride” as a means of strengthening community bonds. The 1989 Chieftain honored two Kiowa freshmen with their own page, documenting their bi-weekly commute to prepare their “beautiful costumes” for performances at Otero Junior College in nearby La Junta. The yearbook’s staff sent a photographer fifty miles to enshrine the performances in a page that notably omitted the term “savage.” The 1960 yearbook included a portrait of an Indigenous man in a roach headdress gazing skyward alongside a paragraph demonstrating the prestige of personifying Lamar’s Savage identity: “I will never graduate… I am the undying SPIRIT of Lamar High School.”

Chief Ugh-Lee prowling Lamar’s sidelines, tomahawk in hand, in 1986.

Alumni interact with yearbooks as conduits of remembrance. However, The Chieftain’s aging pages are also brimming with opportunities to educate Colorado. They trace the history of Lamar’s fervent identity and reflect student desires to fasten unifying community bonds using the “Savage” identity.

Yet that word is absent from Lamar High today. Yuma Indians imagery is similarly missing from The Pit. Just in 2022, revised state laws required ten schools across the state to remove offensive mascots. Moving forward, Lamar’s yearbook will capture the future memories of Lamar Thunder.

The Arickaree Indians of Washington County

After exiting Highway 36 southwest of Yuma, five miles of dirt roads await visitors before they reach pavement again on the way to Arickaree School District. The “Bison Pride” chalk drawing decorating the asphalt is the first reminder of a radical and recent change to the school’s former identity as the Arickaree Indians. The sixty-year-old K-12 building once taught more than 300 children. Nowadays, 100 students from Anton, Cope, and the surrounding countryside comprise Arickaree’s student body, a tenth the size of Yuma High’s and about the size of Lamar’s average graduating class. Despite size differences, the history of Arickaree parallels Yuma and Lamar.

Arickaree’s small alumni base ensures that its yearbook (The Arrow) is much less accessible than Lamar’s. Yet The Arrow reveals a by-now familiar story: a small plains community using caricatured Indigenous imagery to capture a sense of community identity and school spirit. The ‘68 Arrow showcased Superintendent Jones wearing a war bonnet and patterned blanket, while the 1980 edition captured a teacher “dressed as an Indian'' in a fringed gown, and the 1979 girls’ basketball page featured “Determined Squaws” as its headline.

In 2015, Colorado created the Commission to Study American Indian Representations in Public Schools to “facilitate discussion around the use of American Indian imagery and names used by institutions of public education.” From the beginning, the inevitable outcome of this commission was clear to many school districts around the state: an end to Indigenous mascots.

The commission accepted invitations to meet from four communities east of the Rocky Mountains: Loveland, Eaton, Strasburg, and Lamar. While alumni from each district expressed concerns, Lamar had the most reservations about changing its mascot. One former educator welcomed the commission into “Savage Country,” while a current student noted the mascot’s significance among alumni and asked the commission whether “any tribe was ever called the Savages?”

Five years later and with the support of the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute—two of Colorado’s remaining resident Tribes—Senate Bill 21-116 prohibited Colorado schools from employing American Indian mascots without ongoing tribal agreements. It forced districts to rebrand their educational identities in eleven months and mandated the removal of any symbols or traditions associated with Native caricatures. Suddenly the La Veta Redskins, Lamar Savages, and Arickaree Indians were outlawed.

The social fabric of many schools required a reinvention. Fresh coats of paint covered student murals, uniforms received redesigns, and statues were torn down. Old uniforms, logos, and school apparel were evidence of noncompliance that could subject the district to monthly fines of $25,000. Rural Eastern Plains districts, lacking substantial financial support but abundant in agrarian school pride, felt these restrictions more acutely than more affluent communities. The Arickaree School District had to scrounge together finances to replace a depiction of an “Indian chief” on the gym floor, and as the legislation did not offer funding for schools that had to make these changes, Arickaree was forced to rely on donations from alumni to stay afloat.

With the removal of symbols that alumni once rallied behind, Arickaree, and many other communities were left with the task of establishing a new identity. Longtime Arickaree school district business manager Sara Walkinshaw acknowledged that current students adjusted to their new Bison identity “much better than people who’ve graduated.” She went on to explain that school activities are the nucleus of social life in Eastern Plains’ districts like Arickaree, as there are “not a lot of big events where you would meet people except for school and church.” School activities are often the only chance for alumni to reconnect with family, strengthen business ties, and share a unifying experience with their community. As a result, allegiance to the school’s mascot runs deep in the community.

Arickaree’s caricatured mascot resembled others on the Eastern Plains, and the district’s small size accentuates the difficulties of challenging the status quo. Arickaree continues to mourn the loss of its school identity. “Indians” keepsakes still adorn Walkinshaw’s personal office. “Change is hard,” she explained.

The Future

Compared with The Pit in Yuma County, the History Colorado Center is much more tranquil. In its new exhibit, The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever, Cheyenne and Arapaho voices narrate the permanent trauma of Sand Creek and the larger conquest that dispossessed them of their lands. As the exhibit concludes, something unusual confronts guests: three football helmets. Two are from Arapahoe High and Strasburg High, and they demonstrate an ongoing partnership between the Northern Arapaho and Colorado schools. The helmets’ label states that the Northern Arapaho “are proud of the respectful relationship” with each school and the “Indigenous issues” curricula that both districts maintain. Well before SB 21-116, both schools sought Indigenous support for their mascots, resulting in a collaboration that opened up new educational opportunities regarding the violent theft of Indigenous land. The third helmet belongs to Wyoming Indian High School. Its label reads, “Our schools are the anchors of our communities on the Wind River Reservation. Like a lot of other communities, the opportunities high school sports provide are points of pride for our people.”

This spirit of collaboration differentiates these helmets from those belonging to Yuma, Lamar, and Arickaree. Misinformative Beecher Island field trips and Lamar’s harrowing material culture show that non-Natives in Eastern Colorado constructed their agrarian identity without Indigenous voices, fabricating simplified caricatures of Indigenous peoples as bloodthirsty warriors of the past. Yet the old logos, no matter how distorted and caricatured, served an important function in the social fabric of these small communities. New state legislation may have removed misrepresentative caricatures, but it also left behind an unanswered opportunity to bridge this gap.

This story remains unfinished. Is it possible to bridge this divide, and bring tribal support and Indigenous voices to the curricula of rural Colorado schools? As the Wyoming Indian High School helmet symbolizes, even direct descendants of Sand Creek victims can agree with the prideful alumni of Lamar High about one thing: schools are central to identity and remembrance.