Story

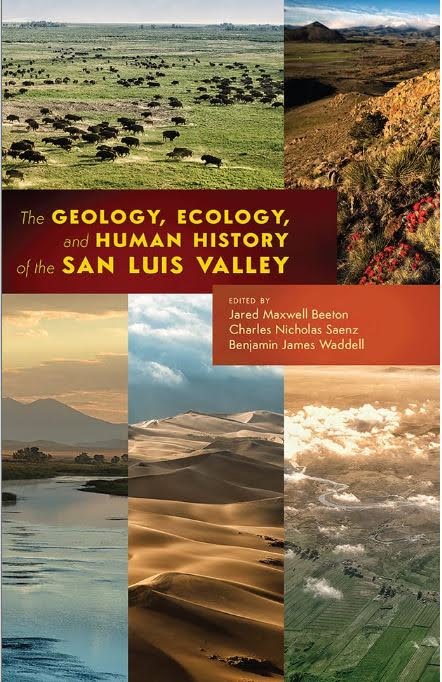

The Geology, Ecology, and Human History of the San Luis Valley

A review of Jared Maxwell Beeton, Charles Nicholas Saenz, and Benjamin James Waddel's 2020 book, The Geology, Ecology, and Human History of the San Luis Valley.

In the Foreword to this absorbing publication, Ken Salazar writes, “Life was simple in the San Luis Valley.…each day, like magic, the sun rose and opened our eyes to one of the most majestic valleys on earth” (p. ix). Salazar, prior senator, US secretary of the interior, and raised in the Valley, aptly defines the sentiments of those intimately familiar with this geological, historic, and spectacular landscape in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

The Geology, Ecology, and Human History of the San Luis Valley is a collection of essays written by knowledgeable scholars that offers a mix of scientific and historical facts, stories, colored maps, graphs, and photographs resulting in a detailed study of the San Luis Valley. As they clarify, the Rio Grande, which in part today separates the United States from Mexico, begins its meandering path on the western edge of the Valley high in the San Juan Mountains. The Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve hug the northeastern boundary, and to the south, the state of Colorado meets New Mexico, each sharing a part of this vast and historically significant valley. In between these edges and boundaries is a “zone of contrasts and transition…exceptional for its diversity in geological, ecological, and human terms.” (pp. 3–4). As the title emphasizes, this is a study not limited to human history or to geologic and ecological history. To adequately appreciate the San Luis Valley, attention to all three topics is essential.

Beginning with the Precambrian geologic period, the book discusses landforms, rivers, glaciers, alluvial fans, and wetlands. How the Great Sand Dunes evolved as the tallest dunes in North America adds a fascinating narrative, followed by how they are currently managed, protected, and preserved. From an economic perspective, chapters on mining include data on methods, types of ore deposits, and names and locations of multiple historic mines in the Valley.

From the chapters devoted to water, readers will become acquainted with the Valley’s aquifers and the naturally occurring groundwater recharge and discharge systems. John Wesley Powell’s 1879 statement is fittingly quoted: “Water in the West is everything” (p. 270). In the San Luis Valley, the Rio Grande and other surface stream tributaries flow but “lose much of their flow by downward leakage into the aquifers” (p. 187). Early residents constructed reservoirs that today are managed and restricted to meet obligations to other downstream states. Land conservation is equally detailed in the book, with the value of conservation defined simply by the statement, “If you take care of the land, it will take care of you” (p. 272).

The book then turns to the topic of mammals and wildlife with accounts about such things as the evening flights of bats that may be viewed from the Orient Mine between late May and early October (p, 211). Carnivores, rodents, and birds are identified, tempting readers to take up birding with sensory expressions like, “If you’ve ever heard the flute-like song of a Hermit thrush…or the warbled song of a Townsend’s solitaire on a spring day, you have experienced some of nature’s most wonderful sounds” (p. 218). An extensive list of various birds is included as well as a list of fish commonly found in the Valley’s rivers and streams. These early chapters serve as background for particulars on the ecosystems and ecology of the San Luis Valley, from grasslands, shrublands, and wetlands to the foothills, montane forests, and alpine ecologies. Ethnobotanical plants are described, complementing brief histories of the Utes, Jicarilla Apaches, Pueblos, and Navajo people who sustained lifeways in this ever-changing environment as they traversed the Valley prior to the arrival of Hispanic culture.

The chapter “Colorado’s Hispanic Frontier” gives a glimpse into early Hispanic settlements that predate the Colorado Gold Rush. Spanish exploration is part of this story, but after Mexico gained independence from Spain, as editor and author Saenz describes, “a flurry of settlement was initiated during the early 1840s…with the intent of expanding Hispanic presence in the region” (p. 342). With the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the settlement flurry subsided and the Valley settled into the vast American West.

Final chapters relate to railroads, Japanese American settlement, issues of political and economic discrimination, and the distinct Spanish language still spoken in the Valley today. Travel itineraries for fly fishing and rock climbing conclude this informative volume. Chapters may be read chronologically or randomly depending on the reader’s interest.

To quote Ken Salazar again from the Foreword, “I believe the natural and human story of the San Luis Valley needs to reach the wider world” (p. xi). This professionally written and comprehensive publication should be shared with readers worldwide as they become acquainted, if not already, with the San Luis Valley.