Story

Aurelio M. Espinosa, Colorado's First Folklorist and Linguist

Born just a few years after Colorado statehood, Espinosa’s studies helped preserve some of the cultural traditions that predate our state.

Editor’s note: this is an excerpt from “New Perspectives on the Traditional Literary Folklore, Music, and Dance of the Río Grande del Norte,” the author's extensive introduction to the recent book Hilos Culturales: Cultural Threads of the San Luis Valley. Available at the History Colorado Center and online on the History Colorado Shop.

Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa was a pioneering linguist and folklorist. He was born in 1880 in El Carnero (The Ram), one of the villages at the northwest edge of the San Luis Valley, when the Spanish-speaking population was estimated at about three thousand.

His grandfather José Julián Espinosa and his family were typical of many Hispanos Nuevomexicanos with their eye on the northern horizon for new opportunities to prosper in the high desert lands of the Río Grande del Norte and its tributaries. Aurelio’s great-grandfather Juan Antonio chose the beautiful valley of El Rito to settle with crops and flocks, but, as its name implies, it was only a little stream and could support just a few dozen families.

An enterprising trader and rancher, José Julián mustered the resources to take his large family, including his fourteen-year-old son, Celso, to the San Luis Valley in 1856. It must have been an inspiring sight after life in the smaller mountain valleys of New Mexico. They settled in the village of El Carnero below the Saguache Range, where there was ample room for their ganado (livestock), and upon which they built their ganancia (wealth).

That wealth included a family library. Celso tended his flocks, but he was also a dreamer who realized that education was the only treasure that could not be lost or confiscated by powerful strangers. In the little school at El Carnero he taught his children to read and write both Spanish and English.

As a young boy, Aurelio spent his summers in the mountains with his uncle tending the family flocks. He was naturally curious about all the songs and stories the shepherds knew to pass the time. Celso decided to relocate his family to Del Norte so his children could attend the high school there; Aurelio graduated in 1898. The family pulled up stakes again to go to Boulder to support the children who decided to attend university. There, Aurelio developed his passion for language and culture. Studying the literature of Europe and the Americas, he was amazed by the consistency and global reach of Castellano, a regional dialect of central Spain that became a world language.

He studied the Romanceros, the great collections of Medieval and Renaissance romances, the millennial ballads named for the language in which they were recited, sung, and written—the earliest form of Castilian, on its journey from Latin to “Spanish.” He was astounded to hear many of them still on the lips of the people of the Upper Río Grande. They had learned them not from books but from the oral tradition. Similar discoveries were being made simultaneously in Spain and later in Mexico, in Chile, and in the Caribbean and the rest of the Hispanic (Spanish-speaking) world.

Little Bear Peak in the Sangre de Cristo Range, photographed from the San Luis Valley in October 1940.

Los Cuentos

As a young scholar, Aurelio Espinosa was compelled, even obsessed, with writing down everything he heard in great phonological detail, especially his huge collection of traditional cuentos (folk stories) that comprised the corpus of his dialectological studies. There are hundreds of stories about courtly intrigues and romances of kings and princesses and commoners. These themes are quite popular in ballads, as we shall see. For some of them, he analyzed and reconstructed their dissemination over the globe. One of don Aurelio’s favorites was the muñeco de trementina (piñón sap doll) stories, so similar to the sticky “Tar Baby” stories from the African American South. True to the Finnish Historical Geographical method in vogue in his day, he collected as many versions as he could find and compared them worldwide to conclude that this particular family of stories began in ancient India and then traveled to Spain and Africa independently. Later a system of tale types was organized. Today folklorists pay much more attention to performance and contextual features.

Espinosa and all his students collected many versions of the following cuentos. These summaries are my own as I heard and learned the cuentos directly from storytellers. In full presentation mode, cuentos are not recited but performed interactively—retold every time as the teller monitors the reactions and backgrounds of the audience. Many, many more stories have animal characters with their deep roots in Aesop’s Fables and more recent roots in the Bible. Here is one about dogs that isn’t in the holy book:

On the sixth day of Genesis, God decided that humans could use a faithful companion, so he created dogs. At first they all looked the same, medium sized and gray. They are so intelligent that they asked God for more. More sizes and shapes and colors. God obliged them. They looked at each other and immediately became jealous of each other. So a big fight broke out. God commanded them to stop and punished them by switching their tails around. Dogs spend their entire lives looking for their own tails, which is why they sniff each other’s tails when they meet.

Espinosa trained several generations of his students (notably Juan B. Rael), his own son Juan Manuel, Rubén Cobos, and many other men and women to continue the task of collecting all the versions of all the stories that people were telling in the Upper Río Grande to compile linguistic data and to analyze their diffusion and origins.

Capilla de San Acacio is the oldest chapel in Colorado. It was built between 1850 and 1860 in the village of the same name; the pitched roof and belfry were added in the 1920s.

With his growing corpus in hand, the young Aurelio amplified and published his dissertation as “The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colorado,” which caught the attention of anthropologists and philologists in the United States, in Spanish America, and in Spain. He became part of an international community of scholars with converging interests. Soon they would found a new academic discipline. From wherever his academic career led him—Albuquerque, Chicago, Palo Alto—Espinosa returned every summer he could to the Upper Río Grande.

His “Romancero Nuevomexicano” immediately attracted the attention and friendship of Ramón Menéndez Pidal, who was simultaneously compiling his own Romancero and language studies in Spain. Pidal’s generation was motivated by a catastrophe: the fall from grace of Spain as a global empire in 1898. After the long wars of independence in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, the United States claimed victory after participating in just the last three months.

The “Generación del ’98” arose from the ashes of the tarnished era of militarism, colonialism, slavery, and its ill-gotten wealth. A new generation of thinkers, artists, writers, and teachers asserted that the true wealth of Spain is not its imperial project but the language, culture, literature, and arts of its peoples, in the peninsula as well as the former colonies. At the universities a new discipline was born and christened “Hispanismo/ Hispanism,” which centered and clustered these interests and not the promotion of the imagined glories of Spain. In the United States, new academic units simply called “Spanish departments” emerged, and Espinosa founded Stanford University’s in 1910. He proudly authored a career total of twenty-two textbooks for use in primary, secondary, and post-secondary education. Many were filled with the folklore of his homeland that students read as they learned grammar, speaking, and writing.

As they established themselves in southern Colorado, settlers like the Cisneros family in the lower Cucharas River Valley (east of the Spanish Peaks) depended on subsistence ranching and farming, enduring privation in exchange for land ownership. Several daughters and nieces got an education and became teachers. Note the tools, sheepdogs, and single-plank walkway.

Espinosa was deeply rooted in his patria chica, or homeland, the center place of his interest and research. He was born four years after the partition of the New Mexico Territory when Colorado became a state in 1876. New Mexico waited more than three decades longer before its statehood in 1912. In Santa Fe, impatient Anglo political leaders conspired with Hispano elites to promote a new Hispanophile discourse, which exaggerated and privileged Spanish cultural influence to disassociate the state and its people with Mexico. Some contemporary scholars see Espinosa’s work as overly complicit in promoting the agenda of this political process and have criticized an invented “Spanish fantasy heritage.” To the contrary, others have pointed out that his dedication to Hispanismo was not about identity formation or politics; it was about language and culture. Don Aurelio’s support for the nationalist cause in the Spanish Civil War decades later intensified the critique. He was ostracized by the American academy, and four decades of solid fieldwork was erased from the canon of US folklore studies, but not from linguistics.

El Romancero

Espinosa was immersed in the issues of his own times, but a few more contemporary indita (Indian maiden) ballads also surface in his collections, and Native characters appear in the stories he heard. Narratives of captivity and mixed ancestry were part of the world of his ancestors but were buffered by silence.

The most famous indita is the legendary "La cautiva Marcelina,"about the woman who witnessed the murder of her entire village and family and was taken away by her captors.

La cautiva Marcelina

cuando llegó a los cerritos,

volteó la cara llorando,

-Mataron a mis hijitos.The captive Marcelina

when she got to the little hills,

she turned back her face crying,

"They killed my little children."-Por eso ya no puedo

en el mundo más amar,

de mi querida patria

me van a retirar."That is why I can never

in this world love again,

from my beloved homeland

they are taking me away."

The ballad is devastating in its pathos and hopelessness and is sung in solitary or ritual settings. In some communities the chorus of "La cautiva Marcelina, ya se va, ya se la llevan" – there she goes, there they take her – could be heard chanted by girls jumping rope. Tragedy is sometimes recalled or sublimated in play.

Gerineldo doing his duty in service to the princess. Illustrations like these can be found in manuscript and printed Romancero collections popular in the courts and privatelibraries.

Sometimes serious, sometimes satirical, the older romances are narrative ballads dating back to Medieval and Renaissance Spain. Favorite themes include history and its heroes as well as courtly love, incest, religion, and pastoral themes. These ballads are often on the lips of children, but, in the Hispanic world, women are their primary keepers and singers. Their main mnemonic device is the sixteen-syllable line with assonance or vowel rhyming in the last two syllables. (When broken in half for easier reading, the assonance is in the second and fourth lines.)

Of the dozens of ballads in the Espinosa “Romancero Nuevomexicano,” several are of abiding interest. One of the oldest is “Gerineldo,” a Carolingian ballad from the court of Carlo Magno (Charlemagne), 748–814 CE. The king personally raised his beloved page, but the princess is also enamored of him and orders him into personal service for only three hours (in her bed).

-Gerineldo, Gerineldo, mi camarero aguerrido,

¡quien te pescara esta noche tres horas en mi servicio!“Gerineldo, Gerineldo, my valiant steward,

if I could snare your service for three hours tonight!”

That morning the king arises early and finds them asleep together. He is obliged by honor to punish them with death, but can’t bear the thought as he asks himself:

-Si mato a mi Gerineldo, que es él que se crió conmigo,

si mato a mi hija la infanta, queda mi reino perdido.-“If I kill Gerineldo he is the one whom I have raised,

if I kill my daughter, the princess, my kingdom will be lost.”

Instead of taking just revenge, he leaves his sword between them in bed. The beloved page is pardoned, marries the princess, and joins the nobility. A rare story indeed, an old favorite among the Sephardim, the Jews of Spain. The Nuevo Mexicano versions are exceptionally complete.

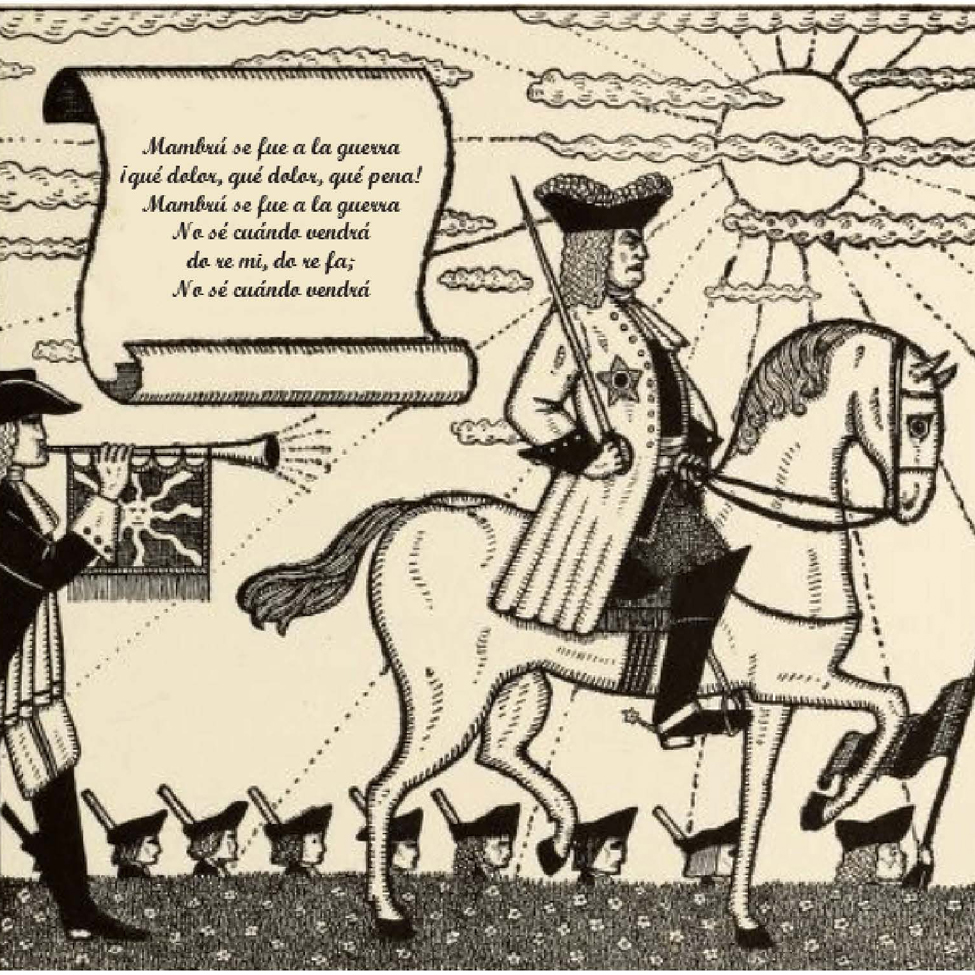

“Membruz,” the Duke of Marlborough, rides valiantly and foolishly to his bloody battlefield. From a Mexican children’s song book.

As with the English Mother Goose rhymes and songs, political romances become satirical when children sing them. This fierce little ballad mocks the downfall of the British Duke of Lord Marlborough, a name difficult to pronounce. Spanish-speaking children the world over perform “Membruz” in singsong style, often while marching around or playing with toy soldiers.

Membruz se fue a la guerra, no sé cuándo vendrá,

si vendrá por la Pascua o por la Navidad.Membruz went to war, I don’t know when he’ll return,

if he’ll come for Easter or for Christmas.Y veo venir un paje, miren, Dominus, ustedes (¡qué salvaje!).

Ya veo venir un paje, ¿qué noticia traerá?I see a page coming, look, Good God, you all (what a savage!).

I see a page coming, what news will he bring?La noticia que traigo, miren, Dominus, ustedes (¡qué me caigo!).

La noticia que traigo, Membruz es muerto ya.The news I bring, look, Good God, you all (now I’m falling down!).

The news I bring, Membruz is finally dead.

In 1709 Marlborough led 75,000 French troops against an alliance of 86,000 English and Spanish troops at Malplaquet, near Belgium, in the bloodiest battle of the bloodiest war in history up to that point. Twenty thousand soldiers died. The world was so horrified that the War of the Spanish Succession was settled by diplomacy, and Bourbons replaced the Hapsburg royals.

Sometimes called relaciones, other romances for children use the antics and crazy vocabulary of animal characters to brighten the world. An entire menagerie of beasts large and small—insects, spiders, and mammals—gather for “La trejaria del piojo y la liendre” (The Wedding of the Louse and the Nit). The setting is San Luis, Colorado, with singer Abade Martínez. There is no priest for the unlikely ceremony, but the godparents are there and the banquet is legendary. The cow takes the bread, the calf provides money, a coyote brings meat, a bedbug offers to cook, and a cricket makes the music. A mouse and a spider agree to be the godparents:

Responde un ratón de su ratonal,

-Amarren los gatos y yo iré a padrinear.-

Tirla, dirla, dirla, dirla dirla...

Responde una araña desde su arañal,

-Síganse las bodas, yo iré a madrinear.-A mouse answers from his mouse nest,

“Tie up the cats and I’ll do the godfathering.”

Dee-da-la, dee-da-la, dee-da-la, dee-da-la…

A spider answers from her spidery realm,

“Let the wedding go on, I’ll do the godmothering."

The monkeys show up to dance, the wine flows, the cats get out and chew on the godfather, the dogs raise hell, and the lice end the fray by shooting their guns at dawn. ¡Ay, ay, ay!

El Cancionero

Your canción favorita, or favorite song, is an everyday usage. But “canción” is also a genre of folk music, the great lyric tradition. There are many hundreds of canciones, old and new, in every region of the Hispanic world, and some are known everywhere. They are beloved because they express every aspect of love and the end of love and life. Since early modern times, singers compiled Cancioneros, or collections of songs, as they did with the Romanceros. Scribes carefully wrote them down, and with the onset of printing they became available as single pages, pamphlets, and books to anyone who could afford them, from the courts to the streets. Narrative stories are much less important in songs than in ballads.

The most common poetic device of the canción is the language surrounding “tú y yo,” simply “you and I,” so we can easily identify with them. The basic building block is the copla, the easy-to-compose four-line couplet. Spanish features vowel rhyming, which is less imposing than the rhyme schemes of English. Our selection of songs was consolidated in the nineteenth century, under the influence of literary romanticism. Bel canto, “beautiful song,” is a fully voiced singing style borrowed from operas of the same era. Music teacher Alex Chávez projected this style when he sang most of these canciones he grew up with in the San Luis Valley.

The canciones Aurelio Espinosa was most interested in were about cultural change, whether the changes in taste between generations or the growing influence of Anglo American society. The earliest were bitter and resentful, but humor eventually took over. Everyone in the Spanish-speaking world has heard of don Simón, the elderly gentleman with his worries and complaints about social and cultural change. His barometer is the dress, hairstyles, and comportment of young women, presumably because their styles change faster. He is a character from a series of nineteenth-century zarzuelas, or Spanish light operas, that were popular in all the major cities of Spain and Latin America. In 1941 in Mexico, filmmaker Julio Bracho directed a movie about don Simón.

In the Upper Río Grande, versions of don Simón’s canción can be dated by women’s styles. In his own time, women were properly and modestly dressed, with long dresses. The old gentleman is scandalized with the outgoing behavior, short skirts, and “rat-tail” spit curls of the “flapper” style of the 1920s.

Don Simón, los sesenta y cumplidos,

bueno y sano doy gracias a Dios.

Que me siento tan fuerte y fornido

que me puedo casar con la flor.Don Simón, sixty years complete,

healthy and happy, thanks to God.

I feel so strong and robust

that I can wed the youngest flower.En mis tiempos toda señorita

se vestía con moderación,

sus vestidos prendían desde el cuello

y sus naguas al mero tacón.In my times all the young women

dressed with moderation,

their dresses hung from the collar

and their skirts down to the heel.En mis tiempos las damas usaban

su rosario en la procesión

y sus ojos humildes mostraban

que rezaban con gran devoción.In my times young women used

their rosaries in the procession,

and their eyes were so humble

that they prayed with great devotion.Hoy las vemos todas encueradas

y con pelo de estilo rabón,

trote y trote atrás de los muchachos,

¡ay, qué tiempos, señor Don Simón!Today we see them with skin showing,

and with their stylish hair all bobbed,

trotting, trotting behind the guys,

oh, what times are these, Don Simón!

Especially alarming to many was the infiltration of English, the second language that became our first language over time—although Spanish maintains its place right next to our heart. From all accounts, this “Cancioncita del inglés” (Little English Song) was used in schools across the region as the language of instruction shifted from Spanish to English. Bilingual humor was key in getting students used to studying English, and making fun of their mistakes. But shaming, punishments, and linguistic trauma were also on the fringes of the curriculum. The first lessons include “yes,” numbers, and greetings, and where there is bilingualism, code switching is always an in-group strategy. Since Spanish syntax is so flexible, both English and Spanish learners often comment that speakers of the other language “talk backwards.”

Bilingual love songs like “Me casé con una pocha” (I Got Married to a Pocha) were a common setting for language shift. English influence began in earnest with the opening of American commerce on the Santa Fe Trail in 1821 and new trade with California on the “Old Spanish Trail,” with its braided routes across southern Colorado. Again, the first new word is always “yes.” Mexicans south of the border were both fascinated and disturbed to witness the assimilation of their cousins across the border. “Pocho” is a word derived from Náhuatl that means pale. In vernacular Spanish it becomes a derogatory nickname for Mexican Americans. The Pochas of California already prefer white bread and butter to tortillas. What is the world coming to?

Tradiciones Espirituales

Any discussion of religious culture must begin with querencia, that notion of tierra sagrada, or sacred space, and the center space of beloved homeland. Historically, the San Luis Valley was a valle de lágrimas, but through a cultural transformation it was sanctified by a system of place naming, ritual celebration, and processions. In Iberian culture, landscapes and nature itself are wild and profane, just the opposite of the worldviews of Indigenous cultures. The ambition of sixteenth-century settlers of the kingdom of Nueva México was to become hidalgos, literally hijos de algo—heirs of land and wealth—at almost any cost.

The price of arrogance was paid in blood in 1680 when the Río Grande Pueblos arose and reclaimed their heritage. In the space of a few mestizo generations, the newcomers who sought title to the land were instead possessed by the land after they returned. As they became indigenous to this place, the narrow boundaries of their Campo Santo, the Sacred Ground, spread past churchyards and the bones of the dead towards valleys, plains, and the mountains beyond. Crosses were erected at sacred sites, and every settlement set up its own nearby calvario to commemorate the Crucifixion of Jesús. Some snowy crosses already graced great mountains such as Blanca Peak, a perpetual sign of hope. Villages were dedicated to saints such as Santiago, San Acacio, San Antonio, the archangel San Rafael, and the Virgen de Guadalupe, which automatically placed them in the sacred calendar. Feast-day processions to honor the santos were always celebrated with processions to bless and re-sacralize the landscape every year. The San Luis Valley is so vast that many became cabalgatas, or equestrian processions, sometimes with hundreds of horses. These traveling devotions feature descansos, or places of rest, where people pause, pray, and sing at sacred spots like the camposanto (graveyard), a chapel, a spring or acequia (irrigation canal), or a place where someone has met their death.

The religious poetry and stories of the people of the Río Grande del Norte abound with holy and ordinary persons in Biblical and local settings, since Bibles were so scarce. Woodcutters in the forest or shepherds in a meadow might encounter or even share their lunch with Jesus or Mary. Children hopelessly lost in a snowstorm were taken to safety by another child, who grateful parents realized was Santo Niño, the Child Jesús, by the description of his clothes. Saints were called upon and thanked for special favors. The beloved San Antonio had a talent for helping find things as small as a watch or as important as a spouse. He could also be punished and his face turned to the wall if he did not deliver his favors soon enough.

Los alabados

Ancestral prayers and prayer poems to be sung had a special place in the memory, the hearts, and the notebooks of the people. A deep and culturally complex spirituality thrives in New Mexico and can be heard in its many-layered religious romances. The ancient alabados (songs of praise) echo Medieval plainchant, sounding stark and spiritual because they are based on modal scales (like Gregorian chants). Alabados are antiphonal when sung in groups, and the people sing the chorus or first verse between all the subsequent ones. Alabados are often sung solo as well. They are not bound by time signature and also feature melisma, where a singer lingers on a note by wavering both above and below it, an ornament common to Jewish and Muslim sacred music and of course to flamenco. Alabados were originally communal, participatory devotions that could be heard in households, chapels, plazas, and at the calvario each community had for outdoor services. The faithful keepers of the alabados are the brothers and families of the Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, or Brotherhood of Our Father Jesus the Nazarene, whose moradas, or sacred dwelling places, grace the landscapes of the Upper Río Grande. Some Easter-season services retreated into private spaces with mounting pressures of tourism and religious intolerance. But they were never secretive, as some would believe. Alabados are heard most often during the Lenten season, and they narrate the Passion of the Christ and the anguish of his mother, María.

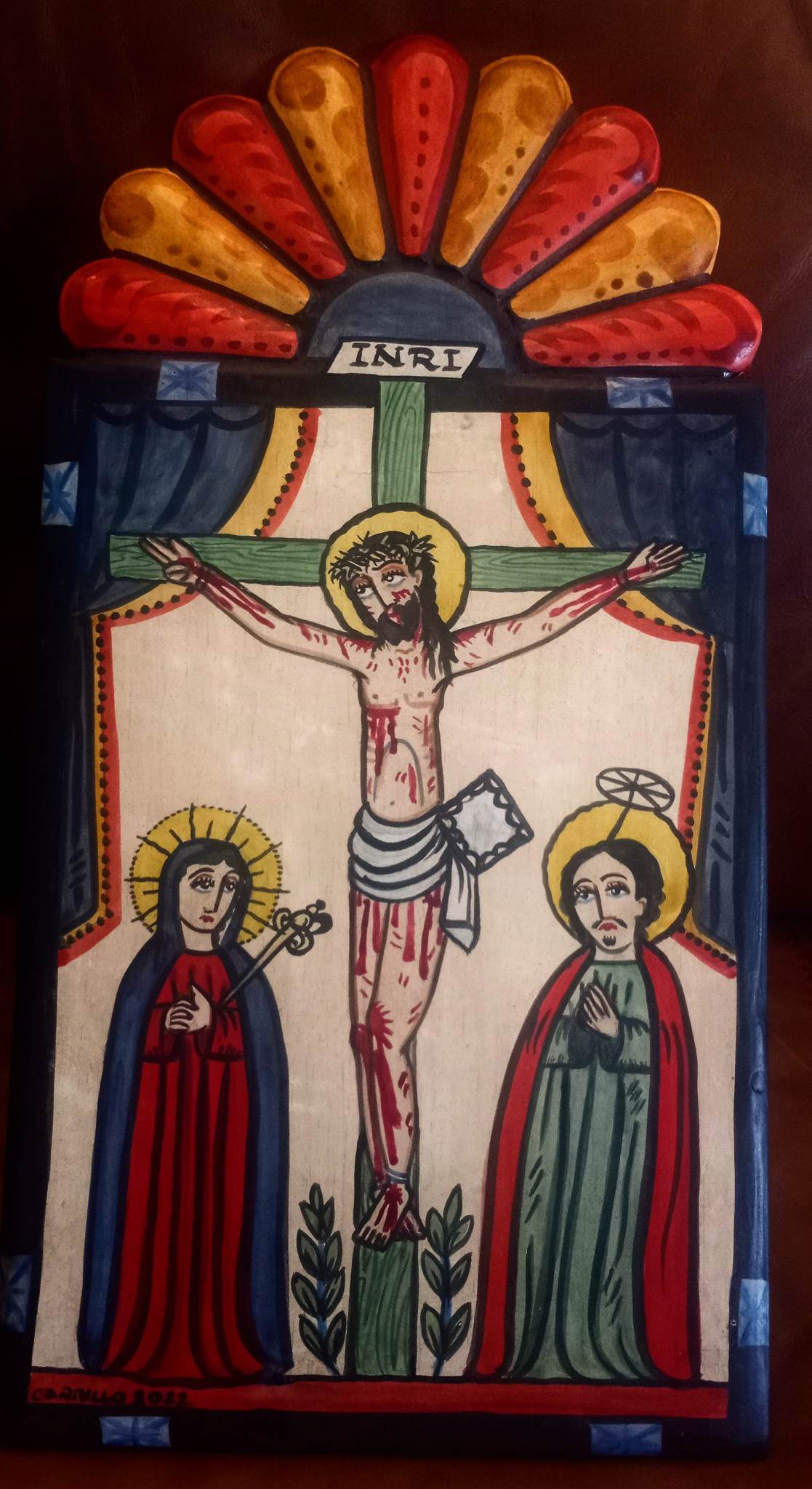

A hand-painted icon depicting Cristo crucificado, "Christ Crucified." Icons such as this are common among Hispano communities in the United States, and across the Spanish-speaking world.

Aurelio Espinosa identified “Por el rastro de la cruz,” or “Along the Trail of the Cross,” as one of the oldest and most widely distributed alabados in the entire Spanish-speaking world. As Jesus proceeds on the Via Crucis (the Way of the Cross), he leaves a trail of blood behind him. The bells of Belén (Bethlehem) are tolling for the dawn, and his Mother is desperately looking for him. She does not meet Jesus directly as she does in the Fourth Station of the Cross. Here, she meets her nephew San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist) outside Jerusalem and faints when he tells her what is happening. Then they proceed to the Crucifixion. This is a sign that not only priests composed alabados, since they knew that only John the Evangelist was present that morning. John the Baptist had already been executed by King Herod.

In “Considera, alma perdida” (“Consider, Lost Soul”), the singer appeals to the skeptical listener, the “lost soul” who is invited to explore the “mysteries of the Cross.” The chorus of this alabado can be heard as a sung refrain between the Estaciones de la Cruz, the fourteen Stations of the Cross, which are recited and intoned with prayers:

Considera alma perdida,

que en aqueste paso fuerte,

dieron sentencia de muerte

y al Redentor de la vida.Consider, lost soul,

that in that fateful step,

they gave sentence of death

to the Redeemer of life.Él que a los cielo creó

y a la tierra le dio el ser

por tu amor quiso caer

al tercer paso que dio.He who created the heavens

and gave being to the earth,

for your love he did fall

on the third, the third step he took.Considera cual sería

en tan respiroso amor,

la pena del Salvador

y el martirio de María.Consider how it would be,

amidst such spiritual love,

the agony of the Savior

and torment, the torment of Mary.Los clavos, ¡qué compasión,

y espinas que le quitaron,

segunda vez traspasaron

de María el corazón!The nails, what compassion,

and spines they removed,

the second piercing

of Mary’s heart!Llegó al ocaso la luz,

entre Cristiano y sin tosa

en el sepulcro reposa

los misterios de la cruz.The light approached darkness,

between Christians and without

in the sepulcher rest

the mysteries of the cross.

Neo-Mexicano and Chicano Renaissance: Visions for a New Future

By the 1890s Hispanos had realized the truth of the ancient adage and ideal of “espada y pluma”—that the pen was as strong as the sword. The sword holds sway over conflict in the moment, but the pen can carry truth into the future.

Before public schooling was available in Colorado and New Mexico, Hispanos embraced the written word, and they learned to read around kitchen tables and in one-room village schools. By the turn of the century, all along the Río Grande corridor from El Paso to southern Colorado, dozens of Spanish-language newspapers were available in cities and towns. Besides news, editorials, letters, advertisements, and legal notices, they offered farming and veterinary advice.

They were brimming with folklore and literature, too, and they offered a space in which oral traditions could be documented. They featured commemorative poems, songs, stories, aphorisms, riddles, stories, classics, and novels in serialized editions. A new generation of progressive journalists began to call themselves “Neo-Mexicanos” to project their voices into a new future. They believed the written word could change society, combat assaults on Hispano Mexicano culture, protect civil and property rights, and promote education and political participation. All over Latin America, newspapers created new virtual communities through print, one of the foundations of emerging nations. In the Upper Río Grande, neomexicanos were imagining a nation within a nation, with its own version of history, its own national heroes, its own literature. From the pages of newspapers emerged a cohort of creative writers, historians, and editors who forged their own intellectual tradition, with surprising similarities to El Movimiento, the Mexican American and Chicano cultural activism that emerged in the second half of the century.

A useful way to finalize our tour of traditional Hispano-Mexicano-Chicano culture is to ensure that we do not get sidetracked into fruitless and endless debates on “cultural authenticity,” since it is often dictated to us by outside authorities who benefit from dividing us and privileging some of us. Anthropologist John Bodine called it the “Tri-Ethnic Trap” in his studies of Taos and the ways Hispanos are relegated to the lowest rung of the ladder of cultural prestige there. In his ethnography of the community meetings that led to the formation of the Río Grande del Norte National Heritage Area, Thomas Guthrie offers a most useful concept of “hegemonic multiculturalism” after noticing who defines the cultural framing and controls that critical process. Of what use is our cultural authenticity if it is policed and assigned to us by others?

We could labor endlessly to construct cultural inventories of Hispano culture: How did our ancestors survive and thrive? What were the elements of their tangible and intangible culture? They were subsistence farmers, ranchers, and traders in a barter economy. They spoke Spanish, they practiced folk Catholicism, they maintained their own values and customs. Transportation was difficult, the frontier was dangerous, but they survived. How many items from that mid-nineteenth-century inventory do we share today when our dominant language is English, when we are part of a global economy, and when we benefit from modern transportation and communication networks?

Some basic values have survived. The importance of family is still paramount. Foodways are much more than nutrition as they form part of our cultural identity. We practice both old and new customs. We are people of faith, but now we live in an increasingly secularized world. We believe in education because it has economically and socially redeems our families—without forgetting who we are, hopefully. The decline of the Spanish language ironically elevates it to iconic status, even though we have lost our fluency and deep knowledge of it and labor diligently to recover it as Spanish Heritage Language in Hispanic Studies—also known as Spanish departments and their international and regional exchange programs and field schools.

What abides is a strong sense of ourselves and our new ethnic status in a dominant society. Fredrick Barth offers us the concept of “ethnic boundaries.” We still have a strong sense of who we are even though our cultural inventory only remotely resembles the inventory of our ancestors. Those boundaries are totally permeable and we receive cultural influences from everyone and everything that surrounds us. We get to choose our cultural influences and adopt musical and dance and literary traditions from other parts of the world. We get to define ourselves.