Story

Bold Brushwork

The early 1920s were a time of creativity and innovation in Colorado. Artist Gwen Meux and her fellow painters were at the heart of a movement working to capture the meaning and spirit of the American West.

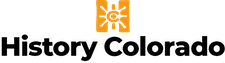

I was captivated when I first set eyes on this painting, freshly unwrapped from its protective coverings in our storage facility: a luminous pink sky, pierced by two upright craggy outcroppings. A single, narrow tree stands between them, providing company to a small human figure moving like a shadow toward the rocks. A full moon hangs rather low in the sky. I was immediately struck by the confident and hospitable color palette, swept up in the movement of the painting and the inquisitiveness of the people painted into the foreground. And then I realized that what I wanted was an invitation to the outing.

Even long-time supporters of History Colorado are often surprised to learn that, alongside pieces of furniture and textiles, photographs and books, our collection also includes pieces of fine art including oil paintings like this one, each with its own unique provenance or place in Colorado history. So aside from my being smitten with this striking depiction of Colorado lifestyle, what tale does it have to tell about what was going on in Colorado in 1923?

For one thing, while the first issue of The Colorado Magazine was rolling off of the printing presses and being delivered into mailboxes, a new modernist art movement was taking shape in the American West, encouraged by vast landscapes and liberties newfound to those who sought them. This Regionalism movement reflected a romanticized vision of the West, depicting optimistic revelations about western life in a time of regional reinvention.

Steak Fry in the Moonlight, by Gwendolyn Meux Waldrop. Oil on Canvas. About 1923–1973.

Gwendolyn Meux found success in the art world at a relatively young age. Born in Newfoundland, Canada in 1893, she began studying art in New Brunswick. She spent the early 1920s firmly establishing herself in the art world, showing her work in two Montreal exhibitions, and studying with Charles Hawthorne in Massachusetts and Kimon Nicolaides at the Art Students’ League in New York. She held two positions as professor of art in New Brunswick and then at the University of Oklahoma. And in the summer of 1923, she studied with artists Józef Bakoś and Frank Applegate, helping to organize the first circuit show of the influential Los Cinco Pintores collective, the renowned modernist group in Santa Fe whose work challenged traditional expectations around landscape presentation. Around this time Meux attended a summer art camp at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where she met A. Gayle Waldrop, then a professor of journalism at the school. She moved to Colorado, where the two were married in 1925.

Meux’s journey may seem like nothing terribly remarkable to young women today, but in the early 1900s most American women were quite new to independently exploring their freedoms of movement and suffrage. Wyoming was the first territory to expand suffrage to women in 1869, and many women in Colorado were granted voting rights thanks to a public referendum in 1893. The Nineteenth Amendment establishing the constitutional right to vote wasn’t ratified until August 18, 1920, so voters in the American West were ahead of the curve, even if discriminatory attitudes kept those rights from manifesting for all women—especially women of color. But those freedoms that had indeed been cemented led to opportunities for independence, career choices, and travel for young women like Meux in 1920s America.

It was a kinetic time in the art world, as Cubism and European influences inspired new artistic movements and the artists who dabbled in them. The Modern Art movement was growing rapidly, and provided opportunities for innovation. Expansion to western states offered a fresh canvas, and artist guilds and collectives blossomed: The Broadmoor Art Academy was founded in Colorado Springs in 1919 by Julie and Spencer Penrose, Wyoming’s Casper Artists' Guild started in 1924, and the influential Denver Artists Guild was founded in 1928, to name just a few.

Breathtaking scenery and fresh air were not the only reasons to venture west, but they were certainly powerful catalysts. Chautauqua centers such as the one in Boulder attracted visitors, especially women, in search of freedom of movement, personal enrichment, and a connection to nature. Women in art schools and communities found inspiration in these elements as well, like members of the Blue Bird Club—young Chicago women, many of them artists and teachers, who visited Boulder and the mountains of Colorado each summer to rejuvenate mind and body. The cultural landscape was changing, and women in the 1920s were embracing the power to decide their own fates.

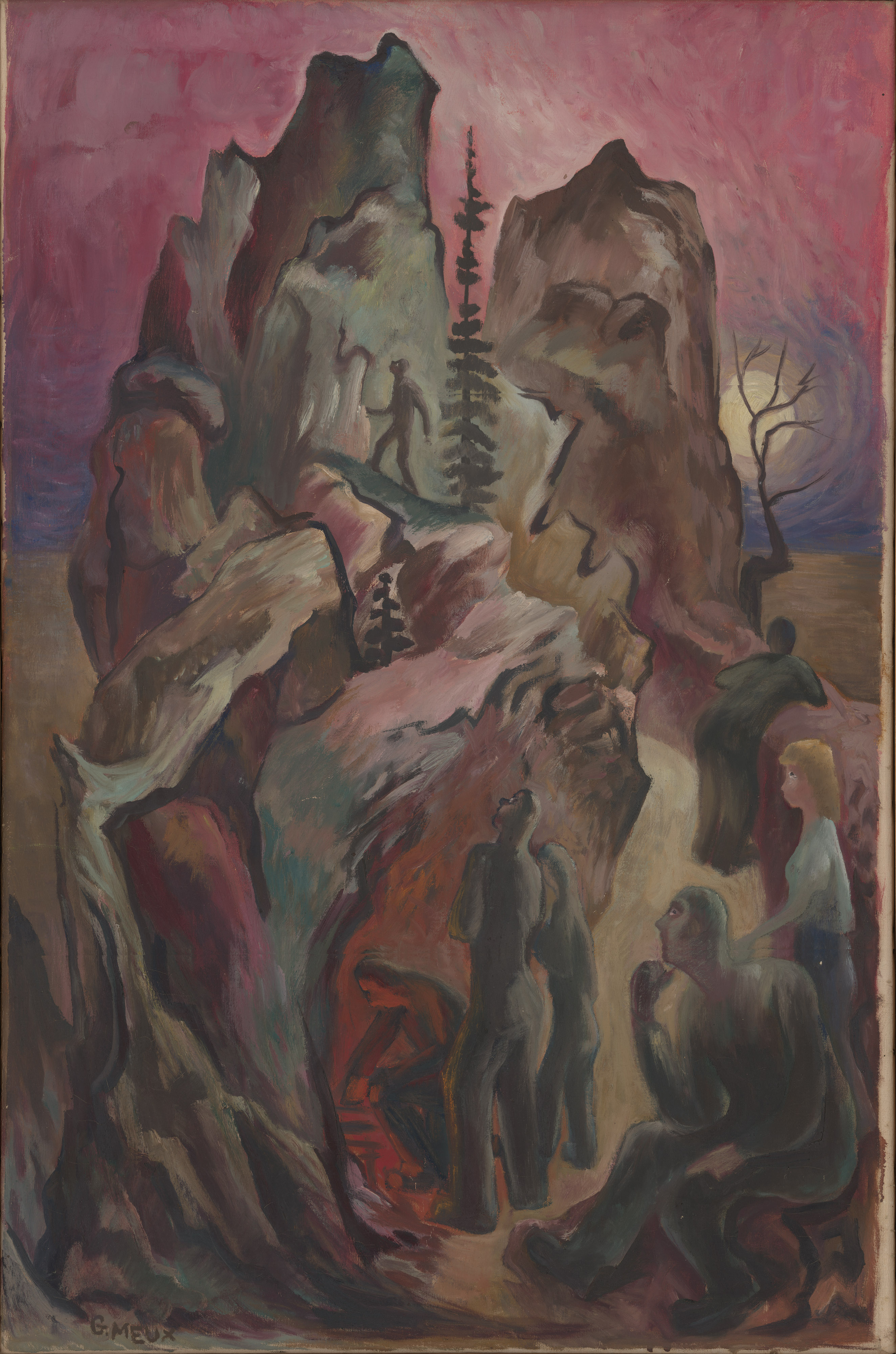

Cabin in the Snow, by Gwendolyn Meux Waldrop. Oil on Canvas. About 1923–1973.

By 1925, Meux Waldrop (she appears to have used both names interchangeably after her marriage) and her husband were settling into married life in Boulder, where she became very active within the budding art community. She was a charter member of the Boulder Artists’ Guild, started in 1925, and became deeply ingrained in the local art coterie as an active artist, and soon a professor of fine art at the University of Colorado. By 1931, Meux Waldrop along with fellow artists and faculty members Muriel Sibell Wolle, Frances Hoar Trucksess, Frederick Clement Trucksess, and Virginia True started The Prospectors, an art collaborative specializing in the emerging Regionalism art movement, also referred to as American Scene Painting. Regionalism may have had its roots in the Midwest, but it was a movement taking hold in the West, too. The Prospectors fostered a strong sense of fellowship by creating works in tandem that also influenced each other's style. In doing so, the artistic cadre fostered a unique feeling of place while exploring this new artistic approach. The group’s manifesto “claimed inspiration from the natural beauty of the mountains and plains of Boulder, as well as the ghosts of Indians, mountain men, and pioneers.” The notable new works highlighted the fresh perspectives in Meux Waldrop’s Modernist Regionalist style, which the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art describes as “vintage regional paintings,” and an early style of Modernism. It’s telling that in the 1920s, The Prospectors and other creative contemporaries imagined many of these new pieces based on the increasingly prevalent romanticized myths of American western culture. The empty landscapes they revered and the ghosts of the Indigenous peoples seemed at the time like blank canvases devoid of the deep history and Native peoples who had populated them.

Nonetheless, Colorado’s mountainous glory not only emboldened her artwork, it energized her personally, to take in—and take on—the rugged offerings of the Front Range. She and her husband were active members of the Boulder chapter of the Colorado Mountain Club, supporting the group’s long-standing leadership in conservation efforts, and she wrote and illustrated articles for its publication, Trail and Timberline, one of the oldest outdoor magazines in the country. In addition to her involvement with outdoor organizations, Meux Waldrop was a long-time member of the oldest women’s literary club in the state, the Fortnightly Club of Boulder, as well as having remained active in the university’s Faculty Women’s Club and Boulder’s local chapter of the Artists Equity Association. Throughout the remainder of her life, she embraced the natural environs and beauty of the town she came to love, as well as the community within it.

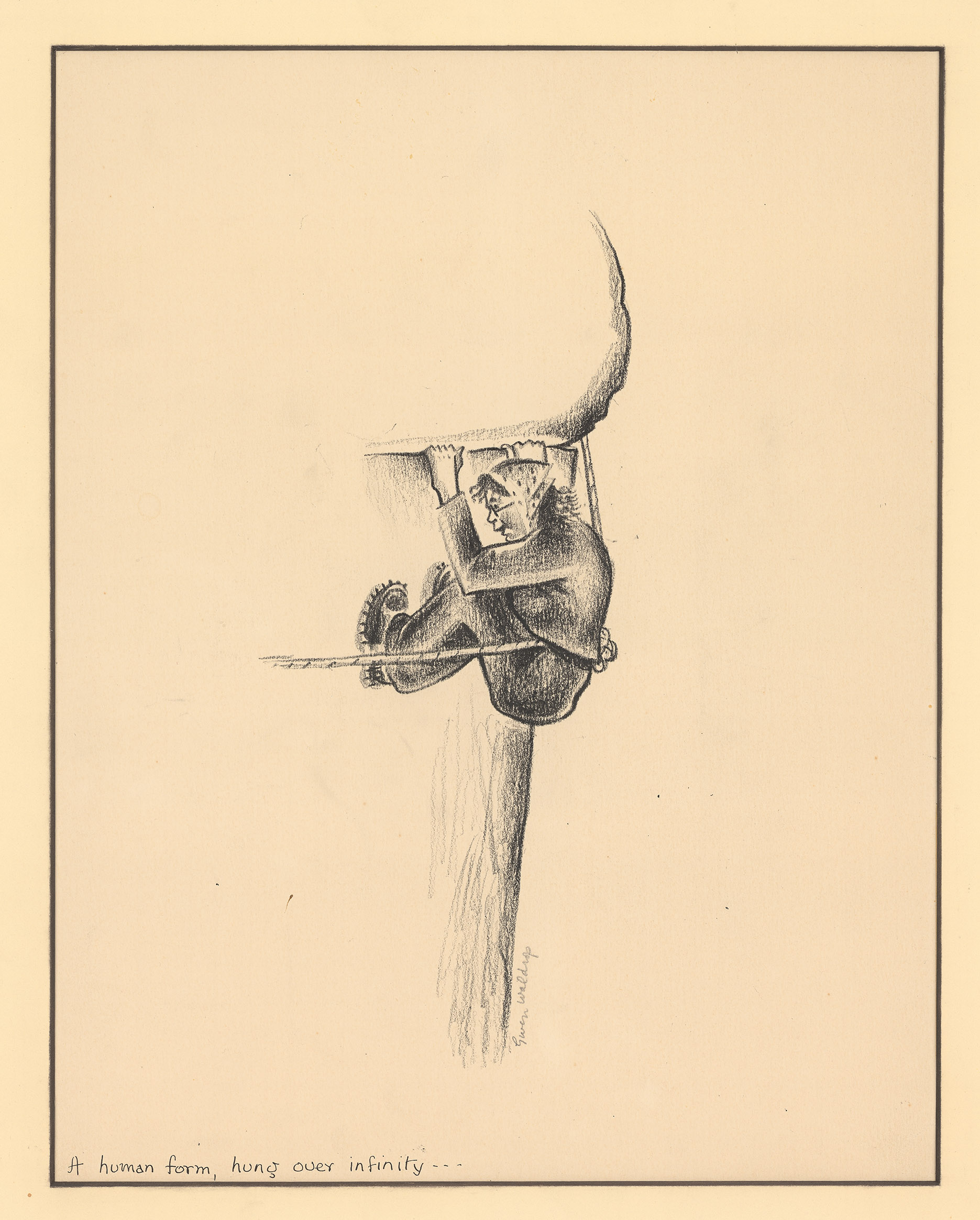

A Human Form, Hung Over Infinity, by Gwendolyn Meux Waldrop. Crayon on paper. About 1965–1970.

Gwen Meux Waldrop was on the path to a successful career as an artist prior to 1923. But her career seems to have catapulted forward that year, with the help of that fateful summer art camp on Boulder’s CU campus not too long after. Meux Waldrop may not have been one of the most famous, or most influential, artists of that time. This painting was purchased a decade ago from the artist’s family estate sale, and later acquired by History Colorado. But Meux Waldrop made her place in Colorado history. Her Hay Stacks painting of a rural scene near Boulder is currently on view at the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art in Denver, and her work has been exhibited in numerous shows throughout the twentieth century. In this, she gave much more back to Colorado than her reputation or portfolio. Through the milestones in her life, we can learn about the options available to women, in many cases for the first time. We can see that she made independent choices about her lifestyle and her career. She involved herself in the community she loved and, in the process, co-founded several organizations that still influence western lifestyle and Colorado art history today. Meux Waldrop followed her passions and inserted herself into her environment, lifting herself and others in the process and strengthening the communities of which she was a part. In today’s vernacular, she would definitely be an “influencer.”

Which brings me back to the Steak Fry. Is this a wildly colorful take on a scene plucked from imagination, or a delightful recap of a joyful outing with friends in the moonlight? I’d like to think it’s the latter, and that Meux Waldrop and her companions have let us have a little glimpse into those days spent enjoying nature for nature’s sake, and for art’s sake. Figures that initially looked mysterious—perhaps even suspicious—now seem rather harmless, standing in the shadow of the rocky outcropping. Their stature is relaxed and friendly, perhaps waiting patiently for their steaks. Are they looking up at the solitary figure in concern, watching to see that this person reaches the top of the rocky hill and descends again safely?

I believe I’d like to be a member of this party. Or perhaps I’m enchanted by what I’ve learned about the painting’s artist, and how I would relish the opportunity to have a conversation with her: As a young and independent woman new to the American West, how did her perceptions of western culture change over time as she embraced the land and the lifestyle? How did the realities she discovered about the West change her, and how did they inform her art over the years? Then again, I’d also ask where her favorite picnic spot was, and perhaps who the grill master was at the steak fry. What an invitation that would be, to sit with friends in the glow of the fire and moonlight, and talk about conquering mountains, both literal and historical.

Meux Waldrop’s work is not simply a lovely explosion of color representing a snapshot of 1923 American lifestyle and landscape on canvas. It reflects so much of her life here in Colorado: colleagues enjoying time together with fascination and wonder in the natural beauty that surrounds. To me, Meux Waldrop’s Steak Fry in the Moonlight is a rather intimate interpretation of community and place—camaraderie, freedom, and shared inspiration in a prospering American West portrayed in colorful brushstrokes—simultaneously complicated by the juxtaposition of mythical perceptions of western culture popular at that time.

Correction: This article appeared in the 100th anniversary print edition of The Colorado Magazine. It incorrectly stated that women's suffrage had been repealed in Wyoming after its initial adoption by the territorial legislature in 1869. The error has been corrected here.