Story

Not All It’s Cracked Up to Be

Ogham, Equinoxes, and Wandering Celts in Crack Cave.

I visited Picture Canyon, located in the Comanche National Grassland in southeastern Colorado, in October of 2015. I was there to see Crack Cave for an entry in a book I was working on at the time, Archaeological Oddities: A Field Guide to Forty Claims of Lost Civilizations, Ancient Visitors, and Other Strange Sites in North America. Though I knew there was some Native American rock art in the canyon, initially that was of secondary importance to me. My interest in Crack Cave was sparked by the claim that there was a message on the walls of the cave, written in Ogham, an ancient Celtic form of writing found in western Europe and dating to as much as 1,500 years ago. I have written extensively on fraudulent ancient inscriptions in North America, most of them dating to the nineteenth century, so I was very skeptical about the significance of the Crack Cave writing.

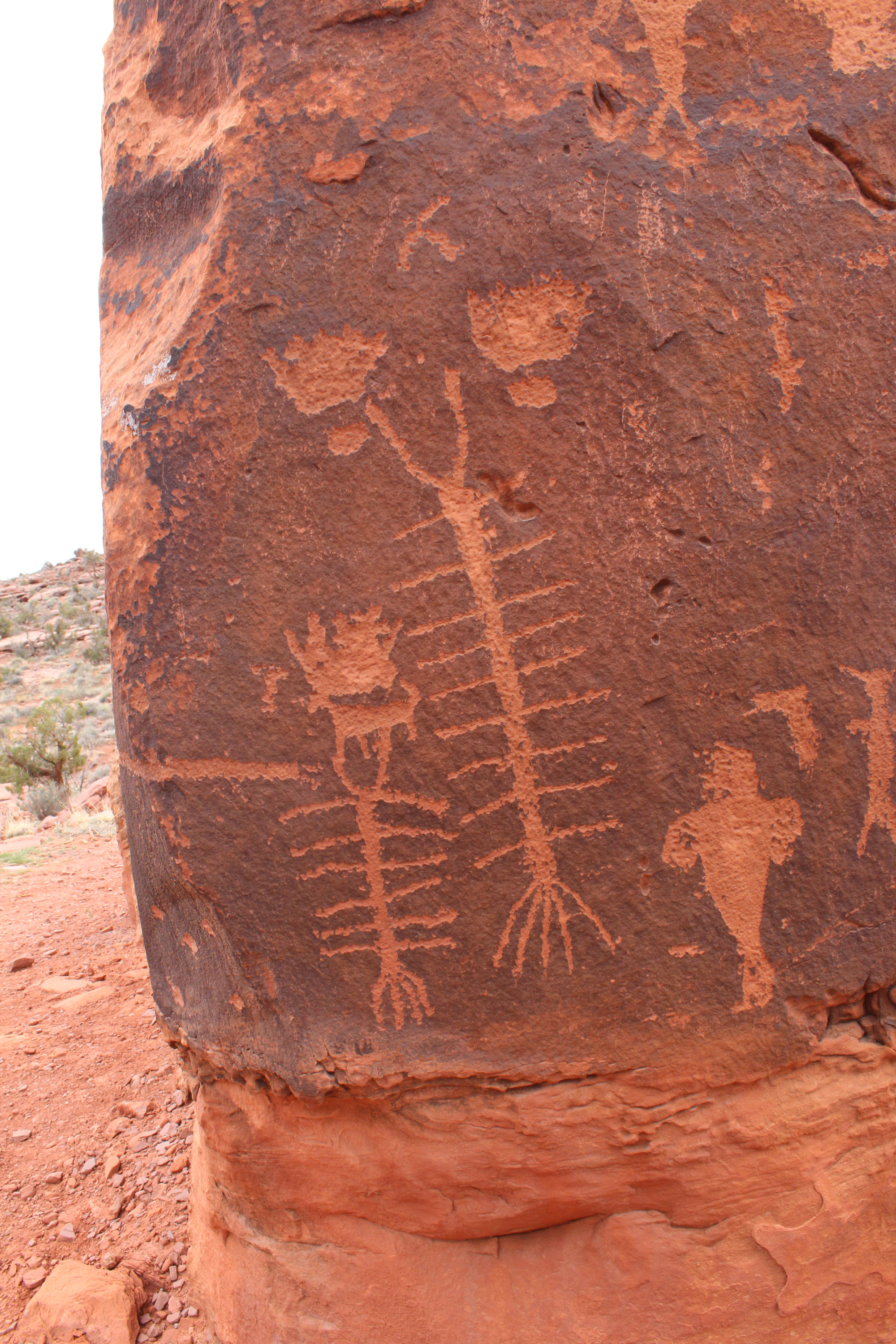

I freely admit that I was unprepared for the extraordinary beauty of the artful messages left by the Native inhabitants of the canyon, likely between about 1500 and 1800 CE. My experience in the aptly named Picture Canyon was the equivalent of a stroll through a vibrant and extensive outdoor art gallery with imagery produced by gifted artists reflecting a style unlike anything I had seen previously in Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, or southern California. I encountered painted and inscribed images of what appeared to be cattle, bison, horses, and perhaps a warrior, as well as a remarkable depiction of what looks to be, at least to me, a sort of multi-legged insect like a millipede. (That image is sometimes identified online as being located in Crack Cave itself. It is not.)

A sampling of some of the marvelous Native American painted rock art in Picture Canyon, Colorado. This depicts a bull, or perhaps a bison.

The genuine messages in stone the Native People of Colorado etched into and painted onto the rock faces in Picture Canyon represent a remarkable legacy of skill, imagination, and creativity. That, however, still leaves open the question concerning the significance of those markings in Crack Cave. What do they mean and how can archaeology help identify and explain them?

Crack Cave and Wandering Celts

I often told my university students that being an archaeologist is a lot like being a detective. Archaeologists and detectives both reconstruct events and investigate human behavior through the recovery and interpretation of items left behind, whether at the scene of a crime or the scene of a life. There is no better role model for that process than the great consulting detective Sherlock Holmes.

For example, in the short story titled “The Adventure of Silver Blaze,” a valuable racehorse goes missing and its trainer is found dead. The wealthy owner brings in Holmes to investigate, when the local police reach an impasse. Holmes visits the crime scene and, in a manner reminiscent of a field archaeologist, lies on the ground and uses his hands to literally excavate in the mud, extracting a crucial bit of evidence, a burned wax “vesta” or match head. The inspector expresses his great surprise that Holmes found anything at all in ground already pored over by his police investigators and the response is both vintage Holmes and revealing in an archaeological sense. Holmes informs the inspector: “I only found it because I was looking for it.”

Indeed, after accumulating a vast storehouse of experience investigating criminality, Holmes knew exactly what should be found if his working hypothesis about the crime were to be upheld (no spoilers here). This is precisely how the disciplinary experience of archaeology informs its practitioners when assessing scenarios concerning the human past, including the earliest human settlement of the Americas, and the abandonment of Mesa Verde, as well as the possible presence of a contingent of ancient Celts in a small cave in southeastern Colorado. Like Sherlock Holmes, we know what to look for if a given scenario or interpretation is true. If ancient Celts were in Picture Canyon, we know what we should find there, beyond the inscription.

The markings in Crack Cave that are asserted by some to represent a unique American version of Ogham written without vowels; the vowels are simply made up.

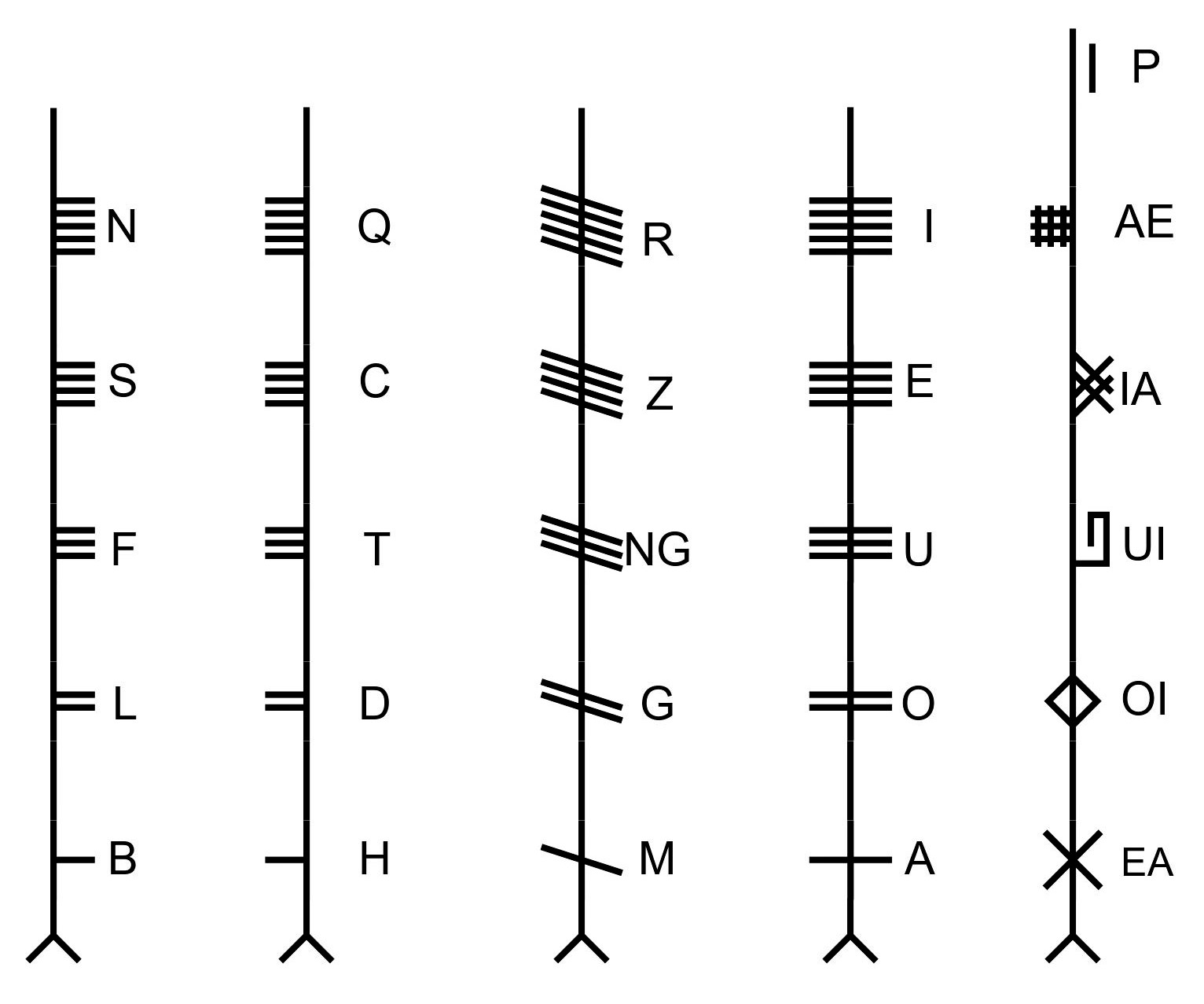

How would Sherlock Holmes assess the purported ancient writing in Crack Cave? For many years local researcher Bill McGlone, among others, investigated the markings there and elsewhere, interpreting them as a form of the aforementioned Ogham, an alphabetic script developed and used by Celts in western Europe between the fourth and ninth centuries CE. A total of only about four hundred Ogham inscriptions are known from Europe, the majority of which can be read as people’s names. Most Ogham inscriptions were carved on upright slabs of stone with specific groupings of horizontal lines representing letters emanating from one or more of the stone’s vertical edges.

Engraving of a typical Ogham inscription on a slab of stone. Groupings of horizontal lines emanating from the vertical edges of the slab can be read as letters in the Ogham alphabet.

Significantly, the purported Ogham in Crack Cave looks nothing like that. Despite this, do the markings there mean that ancient Celts visited and settled in Colorado? It’s an interesting proposal but there are a number of linguistic challenges that must be addressed. Ogham is not, for example, a hieroglyphic system consisting of elements with distinct and recognizable imagery as writing was in ancient Egypt. Furthermore, Ogham is not a formal system of regularly shaped, distinctive, and recognizable letters as is the case for the Latin alphabet I am using in writing this essay. As noted, the individual elements of Ogham simply are lines scratched in rock and there are lots of human behaviors that can produce a series of such lines, none of which constitute a form of writing. Sharpening stone knives by grinding their edges in a soft abrading stone can produce a series of parallel lines conveying no comprehensible message other than the fact that the knives needed sharpening. Tally marks reflecting a counting system or calendar can be etched into a rock surface and to some may resemble—and be misconstrued as—a variation of the Ogham alphabet. Even Native American petroglyphs, for example, those depicting centipedes or millipedes, may include a series of parallel lines that for some may evoke an American version of Ogham.

Admittedly, even just suggesting the presence of Ogham in ancient Colorado is a big deal but McGlone went beyond this and actually translated it. He concluded that the Crack Cave message reads, in part, "Beim La a Bel,” meaning, “Sun strikes here on Bel,” (“Bel” being the vernal equinox).

That translation, by the way, depended on McGlone imaginatively supplying the vowels since, in an apparently unique aspect of American Ogham, it is claimed to have been written only with consonants, despite the fact that European Ogham does indeed include vowels. So, even in McGlone’s interpretation, the etched message was actually only “B-M L H B-L.” McGlone relied on his imagination to fill in the missing vowels to render the message decipherable.

Experts in Ogham note that with only consonants, the interpreter of ostensible American Ogham has free reign to coerce scratches in rock into any one of a number of messages. As a result, confirmation bias rears its ugly head and the reader may be prone to produce a translation that conforms to their own preconceived notion of what the message is supposed to convey. As the late Celtic studies scholar John Carey concluded, the lack of any vowels in the purported American Ogham “makes it so ambiguous that one can extract almost any meaning one pleases for the resulting string of letters.”

Clearly that’s an issue, but let’s ignore, for the moment, my snarky skepticism regarding the identification of the markings in Crack Cave as Ogham as well as my doubts concerning the resulting translation. After all, I am not an Ogham scholar or expert. Fair enough. I am, however, an archaeologist with more than forty years of experience in the field. Following Holmes’s example in “The Adventure of Silver Blaze,” as an archaeologist I know the kinds of things we should find, above and beyond inscriptions, to support the hypothesis that ancient Celts visited southeast Colorado. The same holds true for claims of the presence of ancient Israelites in New Mexico (based on the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone) or Ohio (the Newark Holy Stones); ancient Vikings in Minnesota (the Kensington Runestone) or Oklahoma (the Heavener Runestone); or of additional wayfaring Celts in West Virginia (the Christmas Greeting). Where’s their stuff, where are all the “wax vestas” they must have left behind if they were here?

The claimed discovery in North America of ancient messages written in antique Old World languages was one of the many speculative claims about the human past that inspired me in 1990 to write a book titled Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (Oxford University Press, now in its tenth edition). Those frauds, myths, and mysteries have recently inspired a YouTube series sponsored by the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation in Colorado: Exposing Hoaxes, Busting Myths, and Solving Mysteries. I focus in a few of the episodes on claims of visitors to the New World in antiquity. In one (“Messages in Stone”) I expressly address the claimed existence of comprehensible inscriptions written by those visitors. Crack Cave makes a brief appearance in that episode of the series.

The Verdict of Archaeology

Archaeology is more frequently about the study of trash than it is about treasure. Each group of people, each culture, behaves in culturally prescribed ways in their choice of raw materials, in the ways in which they made their weapons, tools, and pots, in how they fancied up those items to make them aesthetically pleasing, in what they ate, in the ways in which they prepared their food, how they disposed of their dead, and even in the patterned ways in which they discarded their trash. As the patriarch Tevye enthusiastically proclaims in song in the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof, people do things in particular ways as the result of “Tradition!”

That applies to the nineteenth-century Jewish community featured in that show as well as to every other human group throughout history. As a result, each group of people leaves behind a unique archaeological footprint that archaeologists have the training and experience to define and recognize. Stretching the metaphor to its limit, just as Sherlock Holmes was an expert in identifying actual human footprints, archaeologists are practiced at identifying the cultural footprints of different human groups. So beyond the inscriptions, what identifiable archaeological evidence is there, if any, for the presence of ancient Celts in the American Southwest in antiquity?

Though I am not a resident of Colorado, I have it on good authority that it is not a coastal state. So, as the scenario demands, once an ocean-going group of Celts made it across the Atlantic, they might have ended up in the Gulf of Mexico where they made landfall in Texas, and then trudged northwestward toward southeastern Colorado—for reasons that remain opaque to us. They arrived in Picture Canyon, lingering there long enough to track the location of the rising sun during the course of the year and to notice that a wall in the interior of a small cave in a cliff demarcating one edge of the canyon was illuminated by the rising sun on the equinoxes. Figuring that out would have taken, minimally, a year and maybe more to confirm the movement of the rising sun across the horizon, just as was accomplished by the builders of Stonehenge 4,500 years ago. Finally, these Colorado Celts then left a message etched in stone about this celestial phenomenon.

Therein lies the most salient challenge for the supporters of the hypothesis of ancient Celtic astronomers in Colorado. Mysteriously, those Celts left no archaeological trail of encampments and settlements anywhere along their journey across the Southwest. Perhaps those encampments were too short lived and ephemeral to leave clear archaeological footprints. Okay. However, they also left no material trace of their presence in Picture Canyon once they arrived and settled in. They never lost, discarded, or abandoned any of their foreign stuff like iron and bronze weapons; gold, coral, glass, and amber jewelry; the remains of their wattle and daub dwellings; broken bits of their distinctive ceramic vessels with round bodies and pedestal bases; or the buried bodies of their deceased comrades whose DNA could be used to trace their kinship to people in western Europe.

Crack Cave painted rock art depicting a horse with a gracefully elongated neck.

It should be clear that explorers, invaders, and immigrants do not parachute into an area, only to flit away and, in a reworking of the back end of the old expression—“take only pictures, leave only footprints”—they “leave only inscriptions.” Actual people walk around, they lose stuff, they discard stuff, they abandon stuff, they forget stuff, and that stuff is diagnostic of their culture and demonstrably and recognizably different from the stuff the Indigenous People of southeastern Colorado made, used, and left behind. Without the existence of the mundane material that defines and distinguishes every culture archaeologically, it is very difficult for an archaeologist to accept the presence of a group of foreign visitors in Colorado (or New Mexico, or New Hampshire, or anywhere else), whether we trace those visitors to Western Europe, Atlantis, or another planet; by the way, those are actual claims discussed in episodes of the aforementioned lecture series.

Locating, identifying, and recognizing the unique material footprint of wayfaring Celts in New England, the Mid-Atlantic, or Colorado should not be terribly difficult. For example, I have conducted the majority of my archaeological fieldwork in New England (the name of the region might be a little bit of a spoiler here) and we have ample archaeological evidence for the historical arrival of Celtic people there. They brought with them, discarded, and lost: glazed, wheel-made crockery; white kaolin smoking pipes; iron and brass kettles; glass used in windows and bottles; firearms; and a bunch of other bric-a-brac unknown to the Native People of the region who preceded the new settlers by more than 12,000 years. And yes, I buried the lede here. I’m referring to the well-known English settlers of New England in the seventeenth century at places like Plimouth, Hartford, and Boston who actually provide an excellent model for the archaeological footprint of the movement of a group of foreigners into a new, already populated territory.

Okay, but isn’t it at least possible that the equivalent footprint of Celtic culture from more than a millennium ago exists in Colorado, but archaeologists simply have missed it? Maybe, but it’s not terribly likely.

Archaeologists are forever busy surveying, digging, sifting, and just plain searching, so if there were any ancient Celtic artifacts in Colorado, it’s a pretty sure bet that archaeologists would have found them already. Colorado archaeologist Dr. Holly Norton, who was the inspiration for, and champion of, the aforementioned lecture series, has told me that just for the year 2023, archaeologists surveyed nearly 46,000 acres in Colorado. That’s a lot of ground and a lot of archaeology. Have those archaeologists encountered any ancient Celtic sites in those 46,000 acres? The answer is simple: “No.” In a discipline where material objects are the gold standard when it comes to answering questions about the human past, this is an insurmountable barrier to the wide acceptance of the Celtic hypothesis.

Additionally, it is important to remember that Indigenous People did live in Picture Canyon for more than a millennium. Evidence like the Sun Dagger petroglyph on Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon (New Mexico) and the medicine wheels of the Northern Plains (for example, Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming) clearly show an interest and expertise on the part of Native People in using natural, celestial “calendars” to keep track of time during the year. The Native People of Picture Canyon may very well have recognized the fortuitous alignment of Crack Cave with the equinoctial sunrise and kept a kind of tally calendar on the illuminated wall. It is difficult to test that hypothesis but it does have the advantage of not requiring the presence of a group of foreign intruders whose existence in the canyon is, as noted, unencumbered by archaeological evidence.

One of my favorite artworks in Picture Canyon is this depiction of what might be a centipede/millipede or it might simply represent tally marks.

Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Archaeologist

Having started with Sherlock Holmes, it’s only fair to end with the great consulting detective. In another story in the “canon,” “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire,” Holmes is faced with the possibility that the county of Sussex in the south of England is home to a nest of bloodsucking creatures of the night. When his friend, confidant, and chronicler Dr. John Watson asks Holmes if he is actually contemplating the possibility of the existence of vampires in Sussex, Holmes’s response reflects his skepticism: “The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.” Simply put, the real world presents Holmes with more than enough fascinating puzzles to consider without embracing fantasies of the walking dead. I feel the same way about the place that is the focus of this article: Picture Canyon is big enough for us. No ancient Celts need apply.