Story

Fire in the Boneyard

Over a century ago, a vicious academic feud in the Colorado foothills lit a spark—a dinosaur mania that never quite died out.

Arthur Lakes set out from Golden, Colorado on a trek into the rugged foothills around Mount Falcon in the late spring of 1877. It was not a long journey—a few hours of hiking, there and back. Lakes, a clergyman and professor of geology, had set out to measure the depth (and therefore the age) of certain rock formations in the area around Morrison. But what he found there, purely by happenstance, would change the trajectory of his life, and leave a cultural impact so strong and deep that we still feel it.

He found dinosaur bones.

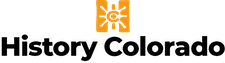

A watercolor by Arthur Lakes, titled “Digging Out Bones at Morrison.” Lakes produced many watercolors during his life, including several of his paleontological digs and expeditions across North America.

Today dinosaurs are everywhere. They’re in hundreds, maybe thousands, of children’s books. They’re on cereal boxes, sports team logos, comic book covers, and billboards. They stalk the toy aisle of practically every store that has one, often outnumbering the more mundane animals. Every few years they stomp across the silver screen to chase after action stars, to the cheers and screams of millions of moviegoers.

The average American probably sees depictions of dinosaurs almost as often as they see those of still-living animals like lions, tigers, and elephants. And probably, for most people, it barely even registers. Dinosaurs have become so universal and pervasive that we don’t even notice.

But when Arthur Lakes stumbled upon those fossils almost one-hundred and fifty years ago, dinosaurs were a rare and unfamiliar thing, even for an academic like him. He was about to set in motion a series of sometimes preposterous events that made dinosaurs the iconic and familiar sight they are today. And it all started in the foothills of Colorado.

Arthur Lakes came to Colorado from England as a missionary and pastor, but his true calling was studing and teaching geology.

This wasn’t terribly uncommon at the time. Academia was a less regulated world. There were no formal training programs for most fields, and the gentleman scholar—essentially a self-trained scientist—could gain prominence and secure positions by virtue of either merit or nepotism. Luckily, Lakes had secured his professorship at the Colorado University Schools (now the Colorado School of Mines) by merit. He was studious, well read, and knowledgeable, and also well-liked. His colleagues knew him to be affable and expeditious, and students appreciated his friendly demeanor and adventurous spirit. He was young, too, closer in age to his students than the typical professor today—he was only twenty-six when he came to the University in 1870.

Seven years later in 1877, he was well-established at the University. He’d taken to teaching with enthusiasm and a hands-on approach. In the years since he arrived in Colorado, he’d sprouted a pushbroom mustache and taken on a near-permanent suntan thanks to his frequent hikes and expeditions into the Rocky Mountains. It was on one of these scholastic jaunts that Lakes made a chance discovery that changed the trajectory of his career.

Few could have made the discovery. “[The fossils] at Dinosaur Ridge don’t stick out very much,” explained Dr. Beth Simmons, a retired paleontologist and former secretary of the Friends of Dinosaur Ridge. “If it hadn’t been for Lakes, maybe those bones never would have been found.”

But Lakes was a skilled geologist, and as his later career would show, he had an undeniable knack for “bone hunting”—that is, finding and identifying fossils.

The fossils Arthur Lakes found that day in 1877 rose out of the nondescript gravel and stone of a hogback ridge like a whale surfacing from the mysterious waters of the open sea. They looked back up at him from the depth of over a hundred million years, hinting at an exciting revelation of new scientific discovery, just out of reach. So he set to work.

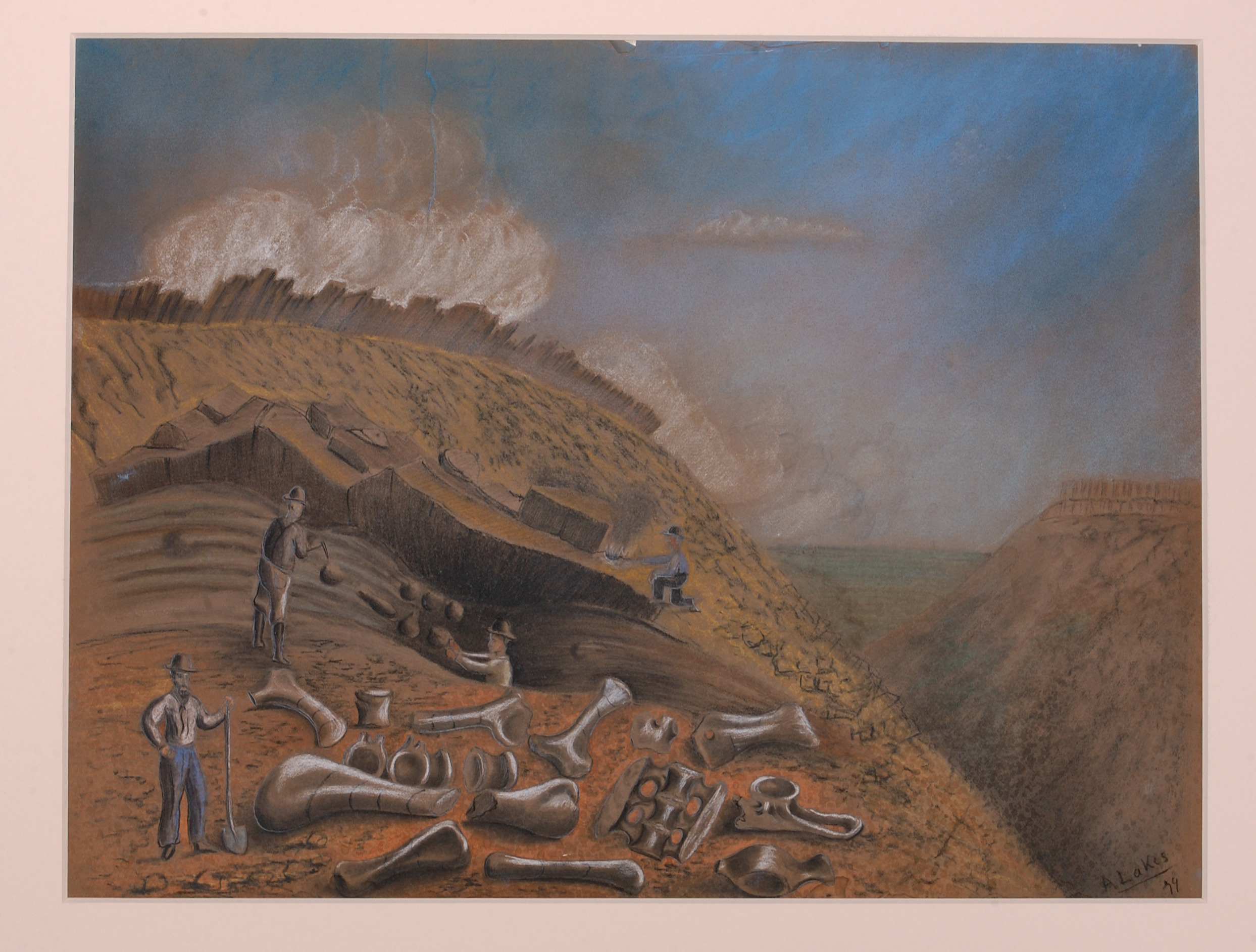

The Dakota Hogback above Morrison, photographed in 1926. The edge of the town is visible on the bottom left.

He knew something of extracting delicate samples from stone, and began work with students and colleagues to uncover more of the find. The fossils, rust-red against the paler colors of the surrounding stone, surfaced slowly. As they did, the enormity of his chance discovery came into focus.

For one thing, they were literally enormous. Most fossils, including the majority of those found at what we now call Dinosaur Ridge, are relatively small and fragmentary. But one of the samples Lakes revealed in 1877 was an enormous vertebra, and it was almost as tall as Lakes.

From our perspective, looking back at the past from a world saturated with dinosaurs, it’s hard to imagine how this would have felt. Even geologists and students of geology at that time had rarely encountered dinosaur remains in their lives. This was a world before cinema, before pop science magazines or sci-fi novels, before even fossils on display in museums. To stumble across a fossil is one thing, but to be confronted with the bone of something so large that its spine was as thick around as you are tall is something else entirely.

Lakes knew plenty about identifying fossils as fossils, and had enough knowledge of biology and anatomy to identify which bones he was looking at. But at the time, that was about as far as his understanding of paleontology extended.

In the nineteenth century, much of academia dismissed the young field of paleontology as an idle curiosity. Most geologists were far more interested in practical applications of their knowledge. This is why there was such a burgeoning group of geologists in Colorado in the first place: they were being trained to enter the mining industry.

“Paleontology was considered secondary,” explained Dr. Simmons. “The gold rush paid for schools and universities, that’s what paid for all the museums. Lakes’ job was to teach geology so we could find more gold.”

The field of biology was a little more refined than paleontology. Darwin’s theory of evolution was a hot new topic on the academic scene, and was still being hotly contested. For that passionate cohort of young biologists embracing evolution, the theory gave them an obvious explanation for what happened to all extinct animals: they were failures. If they had gone extinct, it was because they were not fit for survival. To many nineteenth-century biologists, extinct vertebrates represented dead ends, failed experiments along the march of progress that inevitably led to the evolution of humans. As such, what could be learned from fossils of big, clumsy “thunder lizards” was limited, and certainly much less exciting than discovering new living, breathing species of mammals.

“Back then, paleontology was more a gentleman naturalist’s hobby,” explained Dan Brinkman of the Yale Peabody Museum. “But after the 1859 publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species, and after 1868, the public became interested in fossil discoveries, and what they could tell us about the evolution of life. They wanted to know whether or not you could address these things in terms of Darwin’s evolution by natural selection.”

Arthur Lakes simply didn’t have the background or know-how to properly examine his find, and he also wasn’t too proud to admit that. So, while his students continued to poke up and down the hogback ridge looking for signs of more fossils, Lakes wrote Othniel Charles Marsh, a professor of paleontology at Yale University.

Marsh was already a star, one of the most prominent names in American paleontology. He was a Yale graduate, had studied in Germany—then home to the premier schools of paleontology in the world—and had already financed several successful digs at his own expense. He was a pioneer in his field in the United States, and his work appeared often in both biological and geological journals, which Lakes would have been very familiar with.

Marsh was ambitious, driven, and also very busy—too busy to respond promptly to a letter from a provincial amateur like Lakes.

The days ticked by, becoming weeks, and the enigmatic fossils gathered dust in Arthur Lakes’ office. But he knew the enormousness (both metaphorical and literal) of this find. Likely figuring that Marsh was simply preoccupied with other matters, Lakes reached out to his second choice: prominent (and self-taught) paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope.

Lakes had no idea that with a simple, politely inquisitive message, he had unwittingly fired the first shot in an arcane new type of academic war.

Marsh and Cope hated each other. This is not an overstatement, and would, over the course of two decades of ruthless academic espionage and outright sabotage, become an under-statement.

Marsh and Cope first met in Germany in the 1860s, and it would have been apparent to anyone who saw them even at a glance that they were very different people.

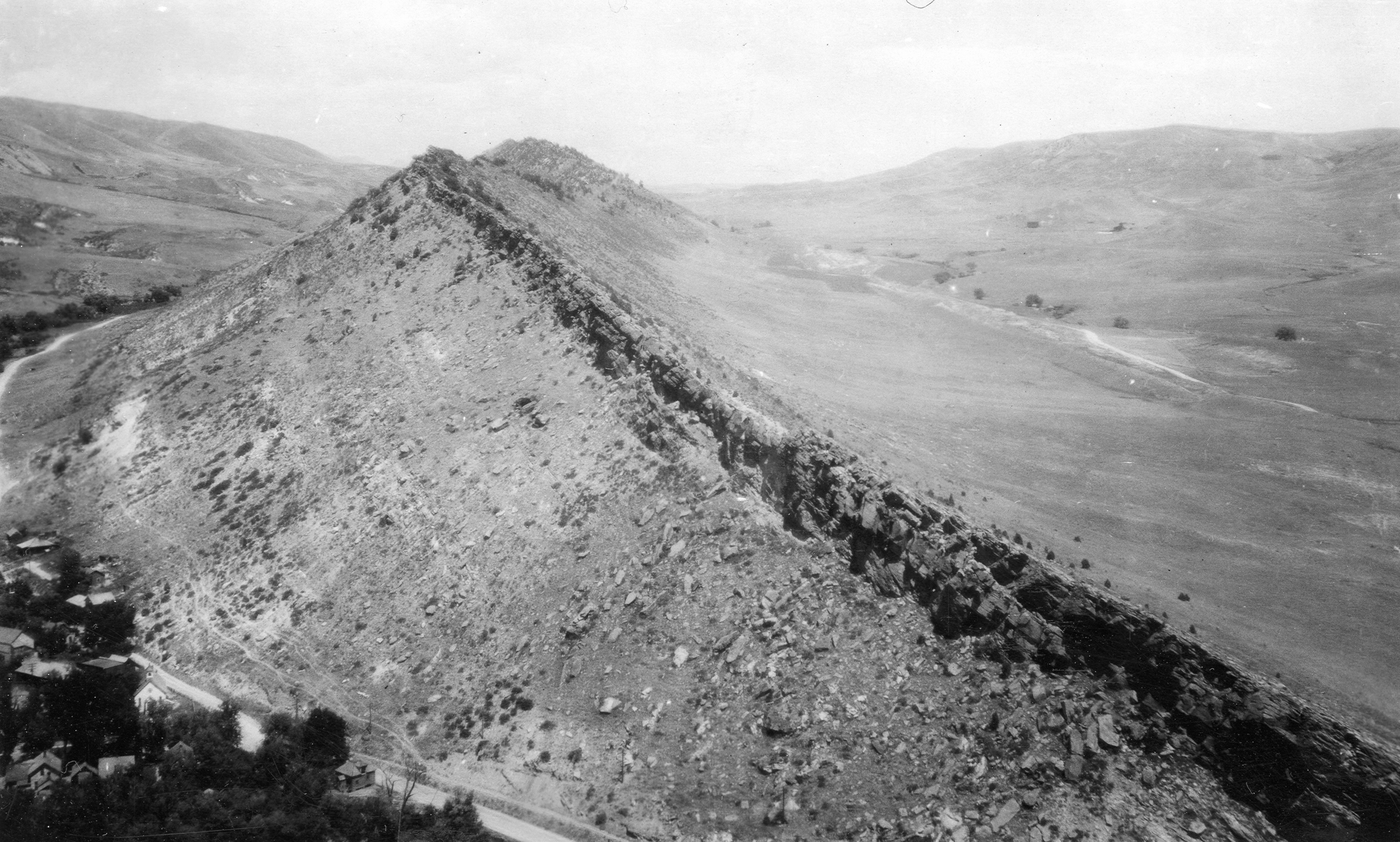

A portrait of Othniel Charles Marsh, aged about 40, during his professorship at Yale.

Othniel Charles Marsh was studying in Berlin, an ambitious Ivy League graduate whose schooling was funded by his millionaire uncle. He was a broad, even burly man, with a round face and a bushy beard, and large eyes that accentuated his penetrating, calculating gaze. He was an inveterate social climber who, while never described as particularly friendly, was shrewd and strategically diplomatic. He knew how to cultivate connections wherever he went, whether in academia, politics, or business. He was perpetually conscious of his reputation, and approached science like a ruthless businessman for whom respect and renown were the most valuable currencies.

Notably, he didn’t enter paleontology out of any great passion. His fiercest ambition was to hold a respected professorship at Yale University, his alma mater, but he had been told that the only such position likely to be available to him was in the new and relatively under-staffed department of paleontology. So he threw himself into the field, his rapid rise fueled largely by determined ambition.

“They both had big egos, don’t get me wrong,” said Dan Brinkman of the Yale Peabody Museum, “but Marsh… his thinking was more self-serving. He was described as being kind of stand-offish, suspicious, and not forthcoming even with people who considered him a friend.”

In contrast to Marsh, Edward Drinker Cope was the child of a comfortably upper-middle-class family. As a boy he attended expensive private schools, but never showed much aptitude for topics that didn’t interest him (and, famously, had terrible handwriting). However, he had a bright and inquisitive mind, and from his teens he began to teach himself anatomy and biology out of books. Once he began attending the University of Pennsylvania, Joseph Leidy—another naturalist and self-taught paleontologist—took him under his wing, and Cope became something of a rising star. By his mid-twenties, he had already published more than three dozen papers.

Cope was open and outgoing, and made acquaintances easily. He was a tall man and well groomed, with a friendly face and approachable demeanor. This served him well during his time in Europe, where he met and befriended some of the most renowned scientists of the day. He had gone overseas to avoid the Civil War draft, as he was a pacifist. However, that does not mean he was peaceful. Where Marsh was methodical, Cope was bold; where Marsh was brooding, Cope was brash; and where Marsh was political and cunning, Cope was blunt, abrasive, and known for his towering temper.

A portrait of Edward Drinker Cope, aged about 50.

“He made friends easier than Marsh,” said Dan Brinkman. “He was more outgoing, but he had a fiery temperament. Wherever he went, he butted heads with his bosses.”

Despite their many differences, the two had a relationship perhaps best described as ambivalent at first, perhaps even friendly. They toured museums together and wrote to one another frequently after Cope returned to the United States. However, once Marsh finished his studies and came back to assume his professorship at Yale, things soured.

Over the years, the differences in their personalities grated against each other, exacerbated by their ambitious and prideful natures. But as the premier American paleontologists of their generation, it was inevitable that they would interact with each other, over and over and over again.

The tension between them began rising early on in 1868, the year Marsh returned to the United States. Cope introduced Marsh to the owner of a quarry which frequently produced fossils. Marsh promptly went behind Cope’s back and paid the quarrymen to send their finds exclusively to Marsh, and no one else—including Cope.

“Unlike Cope, who still viewed [academics] as a gentleman’s pursuit, from the very beginning Marsh viewed it as a business,” explained Dan Brinkman. “And a cutthroat business at that. He was like a robber baron.”

Marsh’s act of espionage undoubtedly irritated Cope, and it was only the beginning. Over the next several years, the two would regularly butt heads, each incident escalating further. They corrected each other’s papers, a normal part of the scientific process but it must have been like nails on the chalkboard of the soul for men with egos as large as theirs. In 1871, Cope went on a dig to Kansas, which raised Marsh’s hackles. Marsh was horrendously possessive and territorial. While he never hesitated to snatch valuable resources from under others’ noses, he guarded jealously everything he could lay even the vaguest of claims over, and that apparently included entire regions of the country. To Marsh’s mind, because he had done a dig in Kansas first, the whole state was his “territory,” and any other paleontologist doing work there was not only a betrayal, it was a threat to his ambitions.

This attitude brought things to a fiery head in 1872, when paleocene mammal fossils were uncovered in Wyoming. Both Cope and Marsh headed out West on expedition.

That long, hot summer in southern Wyoming destroyed all pretense of cordiality between the men. By the time Arthur Lakes contacted them five years later in 1877, even the paper-thin facade of academic politeness had burned away, leaving only a deep, deep hatred.

They were both actively publishing papers on finds in the American West. Cope was especially active, identifying or describing fossils found by miners in Utah, Montana, and New Mexico. However, neither was particularly invested in financing official digs. They were content, for a time, with receiving specimens from afar and frostily ignoring one another's accomplishments.

Things changed when Arthur Lakes’ messages brought them both to Colorado in the early summer of 1877.

Each realized the other was interested in this new site in Morrison. The competitive fires were stoked.

A view of the foothills around Morrison, from the side of Dinosaur Ridge. July 2024.

Both men rushed to Colorado to see what Lakes had found, and to examine the geological formations around what is now the Denver suburbs. But while Cope was putting on the airs of a gentleman scholar, Marsh cut right to the chase. He quickly laid claim to the bones in the best way he knew: with money. He immediately began making overtures to Lakes, the humble Colorado geologist, offering hearty payments and well-financed digs if he continued to seek out fossils for Marsh alone. Lakes agreed to the proposition, as yet unaware of the whirlwind he had just signed on to reap. The Bone Wars had come to Colorado.

You can still see evidence of the excavations Lakes carried out. If you travel to Dinosaur Ridge, as it’s now known, just east of what became the famous Red Rocks Amphitheater and head to the western side of the ridge, you can find a great slice taken out of the hill showing where, a century and a half ago, Lakes and his students carefully carved out and carted away tons of rock. The obscuring sediment and upper strata have been peeled away, revealing ancient bands of stone beneath: layers dating back over 100 million years to the late Jurassic. A few dozen rusty-red fossils are still very visible in the hard stone, left in situ because of the tremendous difficulty of removing them. It can be an overwhelming thing to realize you’re gazing at the remains of animals so long dead that it’s a gift we even know they existed.

“This was once a seashore,” said Alyce Olson, lead tour guide at Dinosaur Ridge, as she pointed out the layers of stone that make up the western, Jurassic-aged side of the ridge. “All of this land used to be flat. All these layers of rock were sand and sediment at the edge of a sea.”

The soft sediment of that ancient shoreline, and the rivers that flowed across into the sea, were perfect for preserving traces of ancient life. And by pure chance those conditions endured for millions and millions of years, capturing hundreds of specimens from dozens of species, across fifty million years from the Mid-Jurassic into the Early Cretaceous. But even more fortunate are the conditions that brought those remains near enough to the surface that a local pastor-turned-geologist could stumble across them on a hike.

“[The ridge] is a hogback, a hill that was uplifted when the Rocky Mountains were formed,” explained Olson. “That’s special. That’s what allows us to see dinosaur fossils.”

The number of specimens Lakes uncovered as he worked that summer was astonishing. It seemed like everywhere he went, he struck fossils. Now that he was looking for them, they were turning up everywhere. The red sandstone ridges and steep foothills of Golden and Morrison were a fertile field of dinosaur bones. By October, Lakes had accumulated several more crates of finds, which he shipped off to Yale to the eager care of Othniel Charles Marsh.

One of the still-visible quarries at Dinosaur Ridge. This one is part of the ridge’s famous dinosaur footprint tracks. The bulges visible in the stone are molds of a sauropod’s footprints, left in river mud over 100 million years ago. July 2024.

From Lakes’ finds, Marsh was able to describe three new species of dinosaur that summer and fall. The first two were the vertebrae of sauropods, those enormous long-necked titans which dwarf every other land animal that has walked the Earth, before or since. Marsh called them Titanosaurus montanus, the Titan Lizard of the Mountains (now renamed Atlantasaurus), and the much-more enduring Apatosaurus. The third find was something different, something special, and so utterly strange that at first Marsh suspected it was some kind of enormous sea turtle. It was a set of jumbled bony plates in strange pentagonal shapes. At the time nobody had seen anything like it before, but nowadays its name is a staple on the tongue of millions of children, and its bizarre form is quickly recognizable: Colorado’s very own state fossil, Stegosaurus.

Marsh was apparently feeling quite triumphant. He published several papers in academic journals, and even gave self-congratulating lectures on these new species at the National Academy of Science. It was quite the feather in his cap.

But while Marsh was paying off Lakes and doing an impromptu victory lap in the halls of academia, Cope was anything but idle. Seeing (and no doubt seething) that he was unlikely to be able to compete with Marsh’s claim to the Morrison area, he turned his attention elsewhere. He made contact with prospectors to the south, following vague newspaper reports of “unusual bones” being found near Cañon City not long before Lakes had sent his letters.

Cañon City is more remote than Morrison, and was even more so in the late 1800s, but it’s no less picturesque. Nestled high in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo range, the landscape is high, dry, and windswept. The whole area is dominated by high ridges that wind across the landscape like primordial serpents, their steep and jagged pinnacles rising out of the Earth like the vertebrae of a great spinal column. They’re of the same age as Morrison’s, and they, too, are a treasure trove of fossils. Digs continue sporadically in the region to this day, exhuming fantastical bones from the earthy slopes and canyon walls.

Once Cope realized what fertile soil he had found, he moved quickly, and began seeking out locals to be his agents.

Marsh heard about Cope’s work around Cañon City and was apparently outraged by yet another example of Cope infringing on what he considered his territory—in this case, the entire state of Colorado. He sent a snappish telegram to one of his agents in Denver, claiming that Cope had “already violated all agreements” and ordering the man travel south to Fremont County and immediately purchase some fossils on display at a local “museum” (really an auctioneer’s office). Marsh’s agent did so, but to his consternation, the fossils turned out not to be a new discovery. They were from a now-obscure carnivorous theropod previously described by Cope in 1866 as Laelaps.

This photo, titled “The Old Graveyard” by the photographer, shows exposed fossilized dinosaur bones at one of Cope’s “dinosaur quarries” when excavation was ongoing in Garden Park, not far from Cañon City. Photo by C.W. Talbot around 1880.

The presence of Marsh’s agent did nothing to deter Cope, who quickly set about making contacts around Cañon City. He made agents of two locals, a schoolteacher named O.W. Lucas, who had discovered the theropod bones now in Marsh’s possession, and a homesteader named Marshall Felch. With the help of these two locals, Cope was able to stake claims in the ridges and foothills around Cañon City and begin digging his own quarries.

Marsh was not pleased by this, and quickly claimed a very petty kind of revenge. Using the theropod bones acquired by his agent, he published a paper tearing apart Cope’s initial description of Laelaps and renaming the species Dryptosaurus. This caused ripples among the scientific community and infuriated Cope. Until the day he died, Cope continued to use the name Laelaps, even long after the majority of the paleontological community had adopted Marsh’s new name.

As Marsh and Cope were building themselves up into a furor and preparing for the next round of their decade-long competition, something was changing out in the world beyond the ivory tower of academia. Both men had been describing prehistoric animal species for years at this point, including several varieties of dinosaur, and they weren’t alone. But something was different this time.

Marsh’s impromptu publicity tour wasn’t staying confined to the halls of academia—it was beginning to reach the public’s attention.

“Before then, dinosaurs didn’t have that place of primacy in scientific literature, and certainly not in the wider culture,” said Steve Belletini, the writer and host for the online science communication series Your Dinosaurs Are Wrong. “Pterosaurs and marine reptiles, like plesiosaurs, would get decent billing. But dinosaurs were kind of just a weird side note.”

“Leaping Laelaps”, a painting by Charles Knight and an early example of paleoart, the artistic rendering of prehistoric animals in an attempt to display how they would have appeared in life. This image was directly inspired by the Laelaps/Dryptosaurus debate between Marsh and Cope, and there are rumors that the fighting dinosaurs depicted are meant to represent the two paleontologists. It was a pop-culture staple for many generations, and still appears in many media.

That really started to change following the discoveries in Colorado. Something about Apatosaurus and Stegosaurus caught the public’s imagination. Reports about the discoveries, and Marsh’s descriptions, began appearing in newspapers. It started slow, but it was definitely noticeable compared to the scant publicity paleontology had received even a few years earlier.

“I suspect it’s a combination of the timing, and the novelty,” said Belletini. After all, nobody had seen anything approaching the size of Apatosaurus before, or anything like the strange body plan and extreme ornamentation of Stegosaurus. “They set the standard for what a dinosaur is.”

As the two rivals began ramping up their digging in the Rocky Mountains, Marsh took notice of this new attention his discoveries were getting. While Cope still had a very ivory tower academic mindset, Marsh was ever the businessman and had a keen instinct for public relations. He knew that the more interested in his work the public became, the more funding for his digs he would receive, and the higher his star could rise. So as the months ticked by and 1877 progressed into 1878, he began to share romanticized and colorful descriptions of these new dinosaurs, really talking up their size, exotic anatomy, and overall monstrousness. The newspapers picked up on these stories, and soon would fill empty space with columns about “Extinct Monsters!” which the Aspen Daily Times exclaimed would have “Made Elephants Look Like Guinea Pigs.”

Header of a 1912 Washington Post article reporting on ongoing paleontological digs in Utah, where several “brontosaurs” and “stegosaurs” (the “most grotesque animal that ever existed”, according to the author) were found.

Arthur Lakes also proved to be a natural spokesman for the dinosaurs. His work in Morrison and association with Marsh made him rather well-known locally, and he soon began giving lectures for the public about his findings. They proved to be so popular and engaging that newspapers would print excerpts. His poetic words brought Dinosaurs to life in the minds of a widespread and eager audience, and with them populated the mountains and plains of Colorado:

“Thrilling stories and catastrophes, filling with wonder the student, or observer, of the earth’s structure, are told by every foot of the ground we tread. You have but to look around you for the satisfaction of your taste for the wonderful. As evidence of this fact, I am going to speak to you of dragons; and reptiles, and weird beings now extinct, which once roamed over these plains and are now found beneath its surface…”

This is how two of the first American dinosaurs to enter public consciousness roared onto newspaper columns like movie monsters making their debut. Apatosaurus and Stegosaurus had captured the public’s attention, and were quickly immortalized as some of the quintessential dinosaurs—a position they still enjoy over a century and a half later.

***

Over the next few years, Cope and Marsh’s bitter feud burst out of the realm of academia and onto the quarries of the American west. It became their very own, bizarre range war as the simmering hatred that had been churning just beneath the surface finally erupted. To both men, it was not enough that they succeeded. The other must fail.

Each man had his claims staked, and rushed to dig quarries, extract specimens, and publish descriptions of new species. They hired larger and larger teams, and sent thousands of telegrams and dozens of train shipments from Colorado to the East Coast.

Things continued to escalate in academic publications as well. The years of chilly silence on each others’ work was brought to an abrupt end by Marsh’s attack against Dryptosaurus, and the two began to fire wild academic shots at one another. They corrected each other’s work, accused one another of plagiarism, and often their allegedly academic responses devolved into a public forum for their furious arguments. It reached the point that at least one publication refused to publish work from either man any further. In response, Cope dug into his inheritance and outright purchased a prestigious academic journal to assume full editorial control, while Marsh simply began bribing other publications to print his papers and not his rival’s.

As their feud raged, Marsh and Cope both sent more extreme instructions to their agents in the West. The two dredged up many of the old tactics they had used in their earlier conflicts in Wyoming, and invented new ones. They began hiring men to spy on one another' s agents. Marsh’s men would learn that Cope’s bone hunters were sniffing around in the South Park and Middle Park, and he would order them to purchase claims before Cope had the chance. Cope’s men would figure out which specimen Marsh was most interested in, so they could tell the hasty Cope which finds to rush to publication before the more deliberating Marsh could write up a description.

The two also began expanding their purview beyond the established quarries near Morrison and Cañon City. They threw more and more money at any prospective find. Word quickly spread among prospectors on both sides of the Rockies that Marsh and Cope would pay top dollar for fossils, and that it was easy to get the two into a bidding war. They raced to stake claims in neighboring states, and some of the most furious competition arose not in Colorado but in southern Wyoming, where the Como Bluff dig site would prove to be the most profitable for both.

In this 1934 photograph, exposed sauropod dinosaur fossils are visible in a Morrison Formation quarry in southern Wyoming. Paleontologists throughout the 20th century built upon the foundation laid by Marsh and Cope, and continued work both in the same quarries and in nearby regions of the same geological formations.

At the same time landowners and cattle barons were fighting bloody battles over the range of the high plains, prospectors feuded over claims and stakes in the foothills. Violent land wars were fought over very tangible, practical resources—grazing and water rights, gold and silver. Marsh and Cope took many of the attitudes and tactics animating the range wars into the world of academia, where nobody would have expected them.

In their haste to accumulate as many specimens as possible, Marsh and Cope ordered their diggers to adopt more and more reckless behavior. Soon enough, the patient methods of carefully extracting fossils Arthur Lakes used to such great success in Morrison were tossed out the window in favor of dynamite blasts. Untold numbers of “less valuable” fossils were heedlessly destroyed to get at the more exciting finds underneath. At one point, Cope’s agents began following on the heels of Marsh’s, taking over in quarries that Marsh had moved on from. They managed to find overlooked fossils, which Cope rushed to publication. Hearing about Cope’s “poaching,” Marsh issued a new order, his most drastic yet: destroy the quarries with dynamite once his teams were done with them. In his mind, it was better the fossils be irreparably destroyed, than fall into Cope’s hands.

Despite their madcap rush and criminally sloppy methods, they succeeded over, and over, and over. As their outfits dug desperately for more and more fossils, the rich Colorado soil was only too happy to provide.

For over sixty million years, the Rocky Mountains had preserved their stores of dinosaur-era fossils. And now that vault had been cracked, these pioneering paleontologists found it didn’t contain the pittance they’d grown used to back east. It had been hiding a treasure trove.

“I have worked at fossil sites across North America, and none of them have the sheer concentration of fossils you have here,” said Amy Atwater, the Director of Paleontology at Dinosaur Ridge. “It makes sense that when early paleontologists were really realizing the potential of North America, they came to Colorado.”

The remains of Marsh’s “bone quarry” in Garden Park, north of Canon City, photographed circa 1906, well after the “Bone Wars” had ended.

Fossils flowed out of the Rockies like a flood from a burst dam. There were more samples—from scattered teeth to full, articulated skeletons—than Marsh and Cope could ever hope to handle. But their ambitions could not be satisfied. They ordered their teams to dig deeper, and more greedily, until thousands of samples were flowing east.

Most of these would never even catch the attention of either man. The goal wasn’t to amass the largest collection, it was to describe the most new species and publish the most noteworthy papers. Almost everything that wasn’t an immediate and obvious asset to this goal was ignored—relegated to the hands of half-trained assistants, who assigned them basic labels and shunted them into storage. The collections at Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Smithsonian are still glutted by thousands of under-examined fossil samples extracted from the Rocky Mountains in a few short years by the madcap digs of Marsh and Cope.

New discoveries are made almost every year just by the dedicated researchers poring over the samples that the Bone Wars barons deemed beneath their attention.

But while Cope’s quarries were just as fruitful as his rival’s, Marsh as ever proved the more able publicist. He shamelessly exaggerated his findings to the newspapers. With each new “titanic” or “monstrous” discovery of a “prehistoric beast” or “antediluvian monster,” the public’s interest in dinosaurs rose.

This was likely a strategic move. He had the soul of a capitalist, not a naturalist, and he knew how to draw in investors. The more attention his finds garnered, the more likely he was to attract wealthy patrons. The more wealthy patrons he had bankrolling his department, the more digs he could finance. And the more digging he did, the more his career would advance, and the further he would outpace Cope.

Most of the “big name” dinosaurs were introduced to the public by Marsh’s publicity hounding. The newspapers crowed about his finds to any who would listen, boasting of the animal’s size and ferocity, and forever burning their names into the American public’s consciousness. The romantic vision of a prehistoric Earth was quickly becoming populated by fearsome hunters like Allosaurus, massive herbivores like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, and bizarre monstrosities like Stegosaurus and Triceratops.

All of these species, whose names still bounce off the tongues of excited children and whose caricatures still stomp across television screens, came from Colorado quarries and were described by Othniel Charles Marsh.

In the 1880s, Marsh’s scheming paid off in a big way, while Cope began to flounder. Marsh had risen to higher and higher positions throughout his career, and was even able to use his economic connections and political clout to push for the creation of the US Geological Survey—with himself as its first (and only) chief paleontologist, of course. Cope, meanwhile, had managed to alienate most of his superiors and financiers with his bluster and temper, leaving him to finance his digs himself. He sold his family’s land and spent the entirety of his inheritance to fund more digs in Colorado, while Marsh financed his digs with government funding and built himself a lavish mansion in New Haven, Connecticut. Cope gambled the remainder of his fortune on an investment in the silver mining industry in Colorado, but he proved to be a much poorer businessman than an academic. He was left bankrupt by the toppling price of silver in the late 1880s, and Marsh successfully cut him out of the federal geological surveys entirely.

Marsh, it seemed, had won. But Cope refused to take this lying down.

***

The bitter rivalry between the two had already entered public consciousness by this point, but only fellow academics then knew the true extent of their vicious hatred for each other—and nobody at all knew the depths to which they had been willing to sink. That changed in 1891, when Cope went public with his accusations.

Marsh’s new government job with the USGS gave him a lot of power, but it also made him vulnerable to public scrutiny. Cope took advantage by publishing scathing accusations about his rival in tabloid newspapers, accusing him of bribery, plagiarism, and political cronyism. Marsh was quick to fire back, and the Bone

Wars erupted back into the newspapers—not as fantastical reports of prehistoric creatures, but as full exposés of the childish and self-destructive bickering of two of the top names in American academia.

It was a low-brow drama, and quickly everyone knew it—including Congress.

Marsh and his supervisor at the USGS both lost their jobs, and in fact Marsh’s position of chief paleontologist was dissolved entirely. Without his cushy government position, and embarrassed in front of all his prior patrons, Marsh found himself suddenly unable to support his lavish lifestyle. He mortgaged his opulent house and was soon left nearly as destitute as Cope.

And that is how the careers of two American pioneers of science ended. Not with comfortable retirements or heaps of accolades, but with two demolished reputations and more debt than you can shake a stick at.

When Marsh and Cope entered the American paleontological scene, it was a largely barren one. All of the noteworthy discoveries were happening continents away, in Europe and India. But after all the dust had settled and their careers had been irreparably demolished, they had populated prehistoric America with dozens of new and enticing dinosaurs.

“In the United States, prior to the Bone Wars, we had like nine dinosaur species described,” said Colton Snyder, Colorado’s State Paleontologist. “They weren’t well-known or popular. But following the Bone Wars, we had over 130.”

Over the next several decades, dinosaurs became a staple of popular culture. As museums began amassing more and more fossils, they hit upon an innovation that in hindsight seems obvious but at the time was a genius business strategy that brought in hundreds of visitors: they mounted the bones.

Paleoartist Charles Knight creating a clay model of Stegosaurus in 1899. In 1982, in response to a public campaign led by elementary school students, the Stegosaurus was designated Colorado’s state fossil.

Mounted dinosaur skeletons showing the shape and scale of the animals as they were in life were not new—a mounted Hadrosaurus had been touring the United States for about thirty years at this point—but they were exceptionally rare. But now, armed with thousands and thousands of samples collected from Colorado and Wyoming, museums not only had the ability to put together entire skeletons, they had the popular interest as an incentive. Tellingly, when the first permanent mounted dinosaur skeletons went up, it was Marsh’s now quite-famous Apatosaurus, on view for all to see at the National Museum of Natural History.

Both of the rivals died not long into this new era of publicity for their science, Cope in 1897 and Marsh in 1899. They left behind a mixed legacy, having both elevated American paleontology to previously unimagined heights, and simultaneously tarnishing it forever.

“At the time, vertebrate paleontology was going through growing pains,” explained Dan Brinkman. “The personality issues didn’t help matters any.”

Paleontology was a young field when Marsh and Cope burst onto the stage, and they each did an incredible amount to advance it. However, they also embarrassed themselves in front of the entire scientific community. They were seen as lunatic mavericks who consorted with cowboys, prospectors, and hired thugs. And worse was the low-brow publicity the Bone Wars had generated.

Dinosaurs were no longer the subjects of academic discourse. They had burst out of the proverbial electric fences and were now stomping around the public’s imagination. They were a novelty, a growing feature of fantasy and science fiction, and so the field that studied them—paleontology—became viewed as crowd-pleasing and un-serious compared to the other sciences. This was a reputation that followed the field for decades.

“We would never talk about dinosaurs. It was considered kid’s stuff,” said Dr. Simmons, recalling her own education. “In my generation, [paleontologists] would end up in the oil industry. Dinosaurs were child’s play. It was fantasy land.”

But it was a fantasy land that the public was more than eager to visit.

People adored the first big dinosaur exhibits going up in science and natural history museums in the 1890s. They were huge draws that quickly became mainstays of museums across the country. Before long, museums were acting almost as competitively and possessively as Marsh and Cope. Dinosaurs quickly became staples of fiction and appeared in countless novels. They were even among the first stars of film. Gertie the Dinosaur was the second-ever animated movie, which featured the eponymous Gertie performing tricks. Notably, Gertie—who would become an icon for American understanding of dinosaurs—was a Diplodocus, one of the species Marsh had described from his days digging in Colorado.

This life-size statue of an Allosaurus looms over passersby just outside the Cañon City Regional Museum. O.C. Marsh named the species from a specimen found in one of the quarries he financed in Garden Park, a region not far from Cañon City which was one of the sites the feuding paleontologists fought over ferociously.

Then came King Kong in 1933, and it brought on a complete paradigm shift. Its popularity changed the landscape of cinema. And it’s telling that the three dinosaurs who rampage onto the screen as bellowing beasts, only to be fought off at great peril by the intrepid protagonists or defeated in primordial combat by Kong himself, are primarily, once again, representatives of Marsh’s finds in Colorado. First comes a Stegosaurus, then a Brontosaurus, and then finally the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex—which, while ultimately named from a fossil found in Montana decades later by one of Cope’s students, first turned up in Marsh’s Morrison 1870s dig as a mysterious (and disregarded) tooth.

The movie-monster dinosaurs in the film awed movie-goers, and firmly cemented prehistoric animals’ place in pop culture. Dinosaur mania was no passing fad. It was a new, eternal feature of the public imagination.

Dinosaurs have left a larger footprint in Colorado than most places in the United States. You can see that clearly in some of our state’s most notable tourist destinations, from the famous Dinosaur Ridge and Dinosaur National Monument to the relatively new Royal Gorge Dinosaur Experience in Cañon City.

“If you’re in Colorado, you’re incredibly fortunate to be surrounded by dinosaurs,” said Amy Atwater, Director of Paleontology at Dinosaur Ridge. “These are places people seek out for recreation, for community, for tourism, for scientific research, for all sorts of reasons.”

And these sites bring in hundreds of thousands of visitors a year, each one a living testament to the popularity of dinosaurs in our modern culture, and of the enduring fame of Colorado’s fossils.

“I think everybody has a general interest in dinosaurs,” said Zach Reynolds, President of the Royal Gorge Dinosaur Experience. “It’s very rare, if ever, that I talk to someone who just doesn’t care about them at all.”

Dinosaur exhibitions remain one of the biggest draws at science museums across the country. They have incredibly broad appeal, and they seem to speak to something nearly universal, some curiosity and fascination that’s present in most of us.

“It appeals to everyone, of every age,” said Amy Atwater. “With paleontology, you have to be able to get your imagination going, get curious, and hold onto your childlike wonder. That’s one of the reasons why it’s a popular science.”

“Certainly kids are dinosaurs’ biggest fans, in general,” said Zach Reynolds. “But people might come in with their kids, expecting the kids to just be entertained, but a lot of times what ends up happening is that the kids run off to play outside and the parents want to stick around and learn more about dinosaurs!”

And if you ever doubt the incredible impact that a few chance finds in the foothills of Colorado had on modern American culture, just wander down to your local dollar store or the nearest supermarket, and pick through a shelf of plastic toy animals. Odds are good you’ll find at least one Colorado dinosaur.