Story

Period Piece: Menstruation's Hidden History

Menstruation is one of the most fundamental human stories. It’s time to tell it more openly.

Menstruators have been using all manner of materials to stem the tide—plant fibers, buffalo skin, sea sponges, wool, lint, paper, even bog moss—since time immemorial. But the first American commercial period products launched in the mid-1800s, with the first patent for a menstrual belt awarded in 1854. As these products gained popularity through the 1920s, the commercial period industry was born.

But pads and tampons are more than just consumer products—they are items imbued with meaning, with social expectations and attitudes towards women, of taboo, impurity, and weakness. These attitudes are reflected in menstruation’s material culture—not just the products, but the stories told about them, especially visible through marketing and advertising. Advertisements over the last hundred years utilize many, often contradictory, narratives—fear and freedom, modernity and shame—that have endured to the modern day.

Colorado has made its own mark on menstrual history, from the invention of the commercial tampon and the development of the Tampax brand, to medical intervention into the safety of these products. Our state has also been on the forefront of pursuing more equitable access for people who menstruate—removing luxury and sales taxes on period products and making them available to students and those in prisons and homeless shelters.

Understanding menstrual history is crucial—it sheds light on the social, cultural, and medical challenges faced by individuals throughout time, helping address issues of access, stigma, and health disparities. Menstruation is a vital part of the human condition, and it’s time to bring it out into the open.

From Hippocrates and the Bees to Ebony

Women have had it pretty rough when it comes to social attitudes towards menstruation. Menstruation has historically been viewed as a symbol of inferiority, disability, impurity, weakness, and rooted in medical myth and cultural taboo.

Hippocrates, the fifth-century physician and “Father of Modern Medicine” believed that menstruating women could sink ships, spoil cheese, tarnish silver, and kill livestock. In the year 77 CE, the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote a thirty-seven-volume encyclopedia which included theories on menstruation. According to him, menstrual blood could make seeds infertile, kill insects, flowers, and grass, and drive dogs mad. Just a glance from a menstruating woman could kill bees.

But it wasn’t just men in ancient times who displayed such fears. A menstruation information booklet from 1943 produced by Kotex listed the “common superstitions of the day” in a section called “When Grandma Was a Girl,” which warned:

If she drank milk, the cows were doomed.

If she entered a wine cellar, wine went sour.

Flowers would wither at her touch….

Meat would spoil if she dared salt it.

A look from her eyes would kill a swarm of bees.

Bees seem to have been in constant danger from menstruating women.

Attitudes towards menstruation arguably haven’t changed much since Hippocrates. We can see this continuity clearly in marketing for commercial menstruation technologies. What are they really selling? Seemingly, products that save women from the shame of their periods. For example, a Kotex ad from 1924 contended that women spend “one-sixth of [their] time in fear of embarrassment”—but never fear!—“Kotex brings peace of mind, poise, and exquisiteness at a time when most women lose it.” Another contemporary Kotex ad assured “concealment,” their product virtually “non-detectable, even under your lightest, filmiest clothes.” Another promises “telltale revealing outlines gone” with their new “Phantom Kotex.”

Isn’t this ancient history though? A relic from the past? Unfortunately not. In the mid-2000s, the compact section of the tampon market grew four times faster than tampons overall, according to a brand manager for Kotex. We still see tampons touted for their compact sizes (a recent ad from U by Kotex described theirs as “comfortably compact”) and for their “discrete” disposal (like the contemporary Tampax Radiant tampon ads), lest anyone find out a menstruator is on their period. Karen Houppert, author of The Curse: Confronting the Last Unmentionable Taboo, Menstruation, writes about this “culture of concealment” surrounding menstruation.

This fear and secrecy used to sell women products relies on erroneous information and can even be promoting potentially dangerous products. For example, menstrual blood does not actually have an odor until it comes into contact with air. But that did not stop the commercial inclusion of fragrance chemicals in tampons complete with ads promoting unnecessary additives.

In an early example, a Playtex tampon ad from 1973 featured a wide-eyed woman seated amongst a large group, with a question splashed across the top of the page: “Are you sure your tampon keeps you odor-free?” Fifty years later, a Playtex Sport tampon box from 2023 features the words “odor shield” in bright, capital, neon green lettering, promising “up to two times more odor protection.” But this is not a harmless marketing ploy. Vaginal tissue is highly sensitive; these chemicals can upset the pH balance which leads to infections, irritation, or an allergic reaction. Reports have even identified certain ingredients in these fragrances as hormone disruptors. All for a phantom problem created from whole cloth to sell more stuff.

You’ve probably seen one of those tampon commercials with overexcited women frolicking in white bathing suits, horseback riding, giggling with glee. This messaging is also not new. Ads from the 1920s also showcased active, radiant women—playing sports, traveling, stepping into cars expressing “how marvelous…the freedom with this new sanitary protection.” Another vintage ad exclaimed that “Tampax makes life worth living!” complete with a beaming woman holding a golf club. Three women jubilantly jump in unison for a basketball in another spread, with the exclamation “Where are the bloomers of yesterday?” Dressed in her tropical-print bathing suit, a woman beams in an ad with the heading “Vacation Discovery! Glorious freedom now with Tampax!” Undoubtedly, better sanitary products made life a lot easier for women. Navigating travel, sports, education, and the workplace is certainly a lot easier with disposable products you can pick up at the store rather than a DIY solution with limited materials.

And yet, even these messages were coded. Women were granted freedom, as long as they menstruated in private, maintaining effortless non-menstruation in public. The key is still hiding your period within the culture of concealment. For example, Kotex ads from the 1920s and 1930s habitually featured glamorous women in silky dresses, with promises that “your poise and charm are safe.” Even the ads featuring women playing sports still promised “no telling lines” (Heaven forbid your doubles partner knew you were on your period). The Modess company had an entire advertising campaign from 1948 to the 1970s which never even featured their period products, no description or what it was for—just impeccably dressed women wearing ball gowns in beautiful locales and the text “Modess…because.”

Historian Tess Frydman describes this coded social narrative as a conflicting cultural expectation of “menstrual regularity and menstrual invisibility.” Women are expected to skillfully manage their period in private so that they could appropriately perform “womanhood” in the public sphere. This “womanhood” refers to what feminist theory scholars describe as “normative femininity”—not who women are, but who they should be as deemed by society—slim, elegant, feminine…and bloodless. Women who don’t openly menstruate (but somehow are still fertile).

Normative femininity also has classist and racial undertones. All of the glamorous Modess models were white, upper-class women. This was not unintentional; much of the marketing represented and was aimed at an aspiring (white) middle-class audience, as historian Jaime Schultz explains. For instance, Schultz describes how ads in the late-1930s through the 1950s depicted elite women playing golf, tennis, and swimming: these were class-based, racially-segregated, and gender-appropriate as seen by their elitism, movement aesthetics, and by the style of clothing they wore. It wasn’t until 1962 that Kimberly-Clark published ads with Black women to pitch Kotex to Black readers. This was in Ebony magazine: There were no Black Kotex models in mainstream magazines targeted at white audiences.

Menstrual History is Colorado History

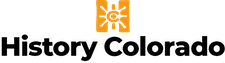

A menstrual device, now part of the History Colorado Collection, was found (presumably) where its owner left it in southwest Colorado over 1500 years ago. Made of yucca fibers and twine, the device would be worn like absorbent thong underwear. Interestingly, this “T-bandage” or belt would remain the predominant design choice for menstrual wear for a long time. As patent drawings and more modern examples attest: women from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries would recognize this device immediately.

This artifact from the History Colorado Collection is thought to be a menstrual “apron” from the Ancient Pueblo people, dated to 500-700 CE.

Some 300 miles north of where this ancient menstrual object was found and over a millennia after its creation in the 1930s, Colorado physician Dr. Earl Haas patented the first tampon with an integrated cardboard applicator, inspired to improve the internal sponges that his wife used. Thus the modern tampon was born. Of course, menstruators have been using tampons for thousands of years—one of the first documented appearances was in ancient Egypt and was made using papyrus plant fibers, but this was the first time an applicator was integrated, commercialized, and marketed for use.

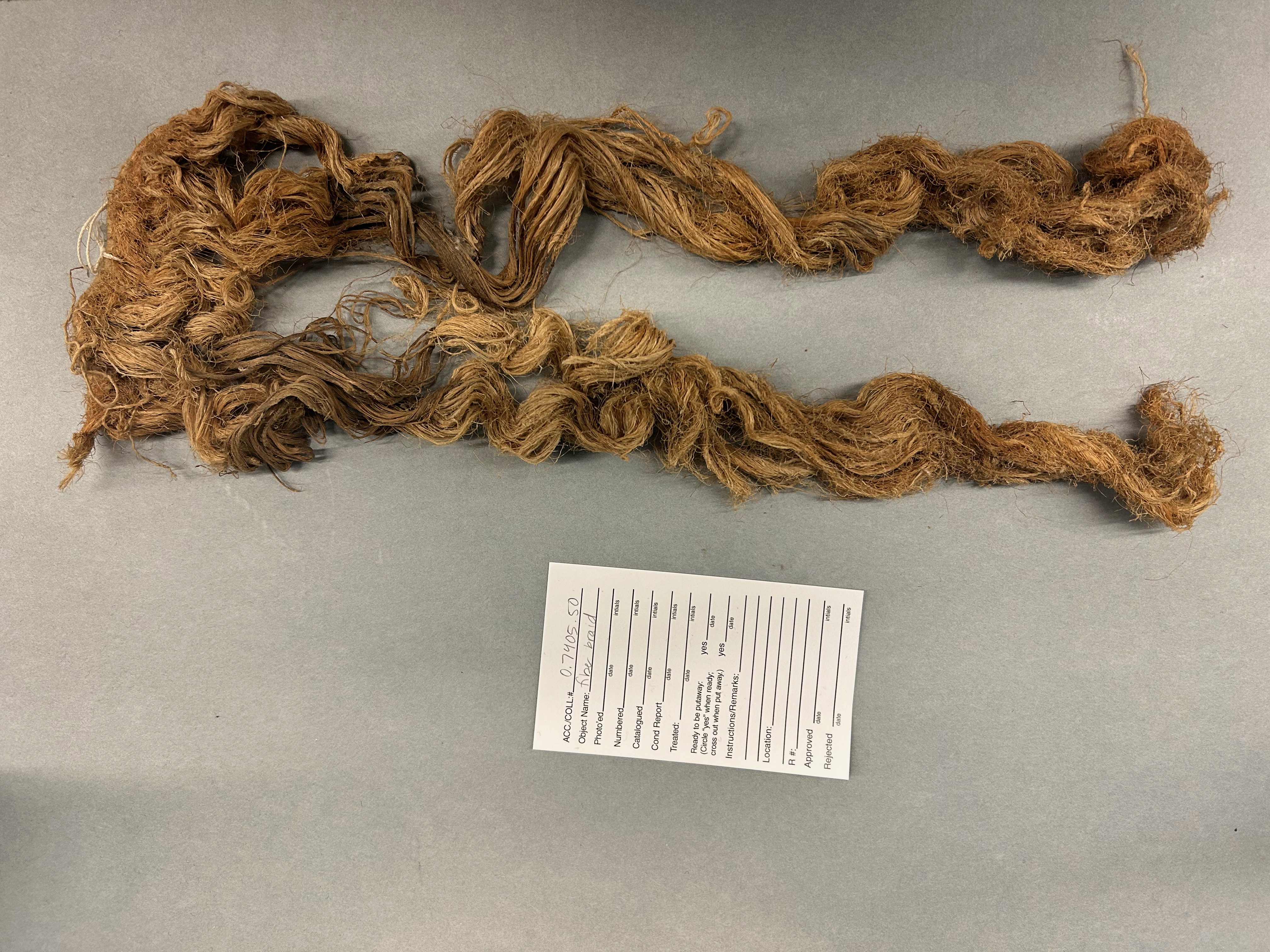

Dr. Haas’s patent was awarded during the Great Depression. Given the economic climate, he had a difficult time marketing his product. After two years, he decided to sell the patent and his trademark—Tampax—to Denver entrepreneur and German immigrant Gertrude Tenderich. Tenderich put her purchase to use immediately, hand-sewing tampons before eventually scaling to using machinery. Her prescient investment would eventually develop into the Tampax we know today—an international, multi-billion dollar company.

One of the earliest Tampax boxes, when they were still made in Denver.

During the 1970s, Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) emerged as a significant health concern, and initially the medical community struggled to understand the cause of the sudden surge in cases.

This changed when Dr. James Todd, working at Children’s Hospital of Denver, made a pivotal discovery about TSS, ultimately saving thousands of lives. His expertise in infectious disease allowed him to better understand that septic shock can come from a strain of staphylococcus or streptococcus bacteria. For the women suffering from TSS, the deadly bacteria was introduced into their system via highly absorbent tampons (left in for far too long) and afflicted thousands. At the time, TSS was a mystery disease that stoked fear throughout the country, not unlike Covid-19 of recent years. But Dr. Todd’s discovery provided an answer and intervention into these potentially fatal situations.

The commercial tampon with integrated applicator came on the market in 1936, but it took until the 1950s for the medical community and the general population to fully accept it. Religious leaders initially denounced them, saying that they would “aid in contraception, sexual pleasure, or both.” Doctors echoed this position, declaring that tampons would be “easily lost in the body and sabotaged virginity,” another example of a lacking understanding of female reproductive anatomy, even within the medical profession. Women couldn’t possibly “invade the vagina” during menstruation.

Advertising campaigns played a large role in reaching the skeptical—particularly with the myth that “unmarried women” (i.e. women presumed to be virgins) couldn’t use tampons, lest their hymenal membrane be broken (the hymen is culturally associated with virginity but that idea is a social construction not based in biology). Ads in the 1940s and 1950s came out addressing this question directly, stating: “of course unmarried girls can use Pursettes!” Many focused on the use of the applicator, so women wouldn’t have to do any “undue handling.” One Meds brand advertisement from 1944 touted their tampons’ “applicators for daintiness!”

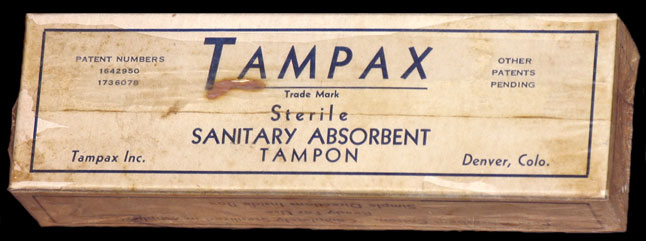

Before the inclusion of adhesives, menstrual belts held pads in place like this Beltx example from the 1960s.

Other campaigns emphasized the idea of modernity and relied on the “modern woman” to sell these new products. One such modern woman in a 1929 Kotex ad exclaimed “If only I could tell this to every business girl!” A Tampax ad in 1938 touted that “college girls lead the way.” A Wix tampon ad from the same year extolled readers to “Be modern!” and another from 1945 that Tampax tampons were “the modern way to think about ‘those days.’”

“War workers” were “strong for Tampax,” too, as a 1944 Tampax-sponsored article had declared. During times of national crisis, traditional gender restrictions tend to ease. This was the case during World War II as the nation came to encourage and rely on women’s formal labor in traditionally male industries. Tampax took advantage and promoted tampons as a “productive wartime technology,” claiming that tampons would help women take less sick days during their periods, maintain the efficiency of work, and of course, bolster patriotism, as historian Sharra Vostral explains in her book Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. One Tampax ad from 1942 showcased a long line of women on an assembly line with the promise blazed across the top: “Objective: Reduction of Female Absenteeism.” Another from Kotex claimed that “You’re the fun in his furlough!” but that “you don’t need a furlough, keep going in comfort with Kotex!”

By 1941, Tampax tampons appeared in fifty-one magazines with a total circulation of nearly fifty million, as historian Jaime Schultz reports. Sales soared for the tampon industry as a result of these marketing campaigns and due to women’s larger presence in formal work and need for these products. It ultimately took two decades from the commercial introduction for the public to finally accept tampons.

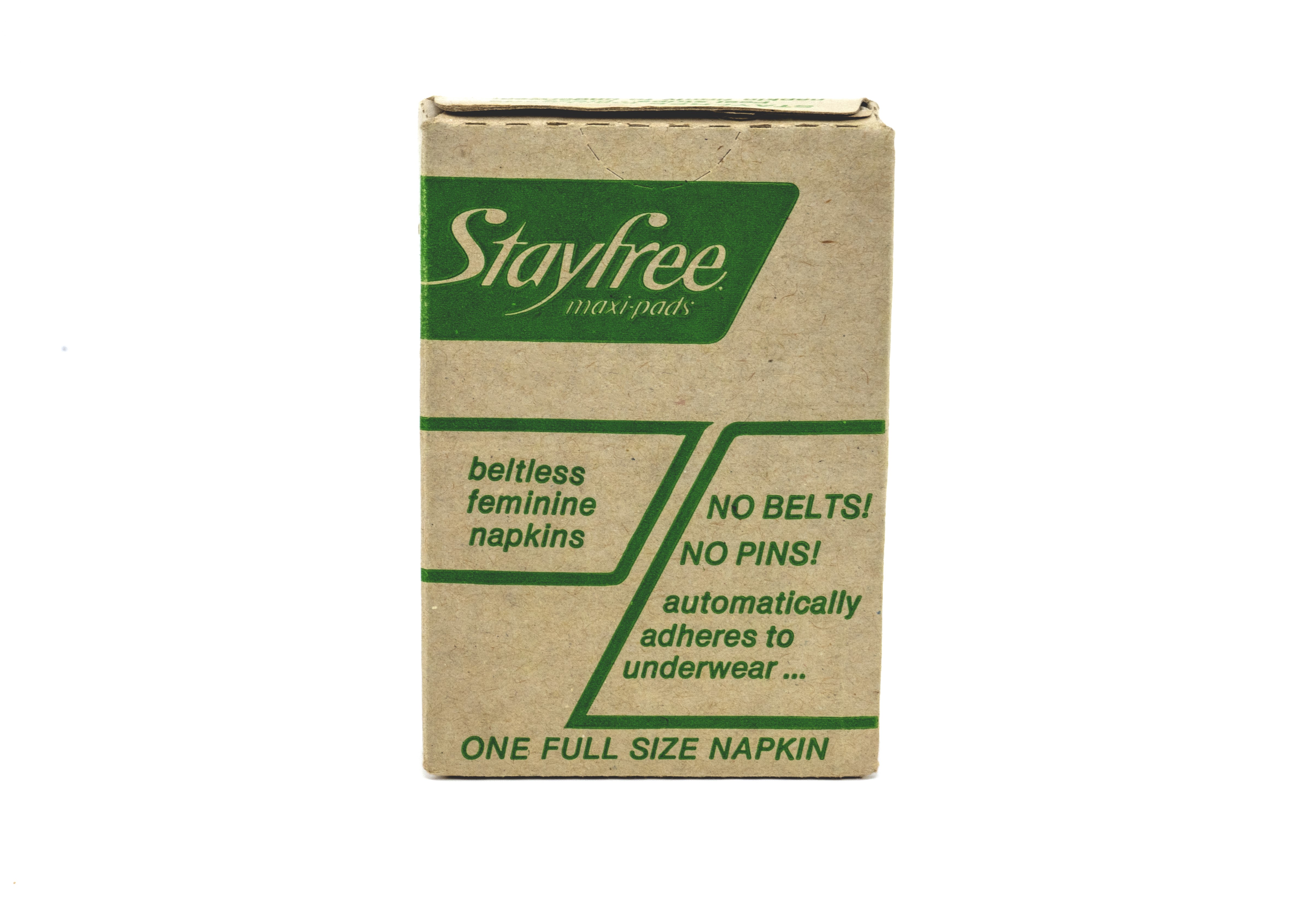

In 1969, Stayfree introduced the first adhesive pad, which rendered menstrual belts obsolete by the 1970s.

Lysol and Toxic Shock Syndrome

Do we just chalk these ads up to ridiculous, outdated marketing ploys? Or are there serious implications of the culture of concealment? Looking through the different marketing campaigns over the last hundred years, themes of shame and fear are remarkably consistent. Even the oft-used term “feminine hygiene” implies menstruation as fundamentally dirty—as unhygienic. Period companies’ marketing continues to refer to menstruation in consistently negative terms, and this reinforces the same message, over and over: that our menstruating bodies are a problem that needs to be fixed (and conveniently, that these companies are the only ones who can help).

Over the years, women internalized this message, which has led to bodily harm. For example, the Lysol disinfectant douche became a top-selling “feminine hygiene” product from the 1930s through the 1960s. It was also touted as a contraceptive device, despite being wholly ineffective and dangerous for this use. An ad from 1934 warns the reader, “Don’t take chances with marriage hygiene my dear, Lysol is safe.” At the time, Lysol contained cresol, which caused burning, blistering, inflammation, and hundreds of deaths.

It wasn’t just Lysol. Non-organic materials were common in early tampons, most notably including rayon, which created a perfect storm of serious health problems. Rayon is more absorbent than cotton, but a byproduct of rayon is dioxin—which is a known carcinogen that can damage the immune system and decrease fertility. And yet, companies were producing tampons with rayon until the 1990s.

Rely tampons were connected to the surge of Toxic Shock Syndrome cases in the 1970s and 1980s, causing widespread fear and illness across the nation.

Synthetic materials in tampons (with their high absorbability) allowed women to wear them for much longer, but also created an ideal environment for bacteria. For a period in the 1970s and 1980s, women who used these synthetic tampons were struck with life-threatening infections, high fevers, dangerously low blood pressure, vomiting, diarrhea, organ failure, and even death. The connection between high-absorbency tampons and these deadly infections was a mystery until a doctor in Denver isolated the issue. It wasn’t until 1975 that Dr. James Todd at the Children’s Hospital of Denver identified “Toxic Shock Syndrome” (TSS) as the cause of so many infections. Between 1970 and 1980, there were 941 confirmed cases of TSS, in which seventy-three women died. Hundreds more were sickened.

By 1980, the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention implicated Proctor and Gamble’s Rely brand of tampons as the single tampon “most contributing” to the onset of TSS, as historian Sharra Vostral writes. Shockingly, even after the report came out, Proctor and Gamble continued to send out millions of samples of these high-absorbency tampons. It wasn’t until 1990, after two decades had passed since its onset and TSS affected an estimated 60,000 people, that the FDA took action and required industry-standard ranges of absorbancy and labeling on packages. Even today, there are no federal regulations that require menstrual companies to disclose what is in their products, leaving their products a potentially dangerous black box to consumers.

Period Culture Today

The culture of concealment that still infuses menstrual marketing entrenches myths, stigmas, and stereotypes. According to Planned Parenthood and the Guttmacher Institute, twenty-two states mandate schools teach about reproductive health, and just thirteen require teachers to share only medically accurate information. When reproductive health is taught in schools, classes are often gender-segregated—so boys aren’t learning about the biology that shapes the lives of half of the population. However, it has been shown that education decreases stigma, stereotyping, and misinformation. Numerous studies, including a 2016 study supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and a 2020 study in the Journal of Adolescent Health based on three decades of research, demonstrated that lack of sexual and reproductive education leads to more sexually-transmitted infections, more unintended pregnancies, and continued ignorance about common illnesses. For example, serious conditions like endometriosis (a common condition that causes severe pain, infertility, and heavy bleeding) are underreported and under- or untreated, and ignorance about common medical issues can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, worsening health outcomes. Lack of knowledge perpetuates stigma and misinformation, preventing individuals from seeking proper care and making informed decisions about their health.

The real curse is the idea that the very biological machinery responsible for perpetuating the species is somehow dirty or toxic, as obstetrician/gynecologist and TED Talk speaker Jen Gunter explained in a 2022 presentation. Women suffer when shame and secrecy are the norm, creating and encouraging an environment without adequate oversight leading to serious physical and emotional harm.

One of the issues stemming from this environment of secrecy is known as period poverty–being unable to afford necessary products, or not being in a position to procure them. However, recent changes reflect a growing recognition of menstrual equality as a vital component of public health. For example, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, twelve states and the District of Columbia provide menstrual products in schools, twenty-four states (including Colorado) provide products in correctional facilities, and at least three states provide them in homeless shelters. Several Colorado colleges and universities already provide free menstrual products to students and faculty. Governor Jared Polis just signed a bill into law in June of this year requiring Colorado middle and high schools to provide free menstrual products to students by 2028.

Vintage Tampax boxes from 1960, 1980, and 1990 showcase the brand’s early designs and the evolution of one of the first commercially successful tampon brands.

Greater access to menstrual products is important because, as a study in 2021 showed, the lack of access has jumped five percent, to nearly one quarter of those surveyed. Lower income and students of color have been particularly affected. The study found that almost a quarter of Latina/x students had to choose between buying clothing and food, and almost half of Black and Latina/x students reported that they felt unable to do their best school work because of lack of access to period products. In a 2024 study, the Denver nonprofit Justice Necessary found that eighty percent of female teens in Colorado have missed class due to lack of menstrual products and ninety percent have unexpectedly started their periods in public without proper menstrual products on hand. Teens often lack access to funds to buy products because they typically do not have steady sources of income or depend on parental support. Additionally, financial constraints within families can mean prioritizing other essential household expenses over purchasing period products, leaving teens without the resources they need.

Some states have removed the luxury tax on period products and some do not charge sales tax at all—slightly improving the accessibility of these already costly items. This is the case in Colorado: sales of period products have been exempt from sales and use taxes since January 1, 2023. These policies are small improvements for access (we wouldn’t necessarily champion toilet paper being more available), but these changes are increasing availability of necessary products, allowing for more equal participation in school and sports, and hopefully moving towards greater acceptance of menstruation as a fact of life for many people.

New, women-led companies have come to the market which aim to destigmatize sexual and reproductive health, and more organizations and individuals than ever before are vocal about period poverty, body literacy and positivity, and period stigma. There are gender-neutral companies as well, with slogans like “for everyone who menstruates”—working to combat the invisibility of the multitude of people who menstruate who may also be non-binary, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, or transgender. Their products are wider-ranging, including for example absorbent underwear which look like boy-shorts or boxers.

Are social attitudes to menstruation changing? In many ways, yes. Manufacturers have had to listen to the public’s demand for better options (like all-cotton products), advertisements have become more open (with actual products featured, no more blue liquid!), and new, period-positive companies have flourished. And yet, the tampon box is still opaque: companies resisting disclosure of their materials has led to public harm–from early rayon use in Rely tampons in the 1970s, to toxic materials found in tampons even today. A 2024 study by the University of California, Berkeley, detected toxic metals such as lead and arsenic in more than a dozen brands of tampons sold in the US, the European Union, and the United Kingdom.

I continue to ask myself—how much has changed from the early days of the period industry over a hundred years ago, when the products and the advertisements and the messaging came from people who don’t menstruate, created for people who do? Menstruation is more than just a biological function; it is a narrative interwoven with cultural, social, and economic threads. The evolution of menstrual products—from ancient devices to modern tampons—mirrors broader shifts in societal attitudes and medical knowledge. Despite some advancements, menstruation remains enveloped in a culture of concealment and stigma.

Contemporary efforts to destigmatize menstrual health and address period poverty are crucial steps forward for public health. By fostering open dialogue and increasing access to menstrual products, we can move towards a future where menstruation is recognized as an aspect of human experience. Menstruation is a human story, one that requires biological, economic, social, and historical lenses to fully comprehend.

In short, the bees are safe.