Story

By Rail and River

Amidst one of the worst economic downturns in Colorado history, two ill-fated contingents of “Coxeyites” tried unconventional means of joining a nation-wide protest movement.

A train robbery was in the headlines of southern Colorado newspapers in the spring of 1894. Not the Hollywood version of a stickup on rails. This was the theft of an entire train.

The several hundred labor protesters who liberated the train from a Pueblo rail yard managed to take it more than two hundred miles, even rebuilding tracks by hand as they went to avoid capture. Though stopped just across the Kansas border, the protestors brought widespread attention to their cause and most avoided any consequences for their heist. At the same time, in Denver, another group constructed homemade rafts and attempted to navigate the Platte River. The rafters were less successful than their rail-bound brethren: Attempting to navigate the river at flood stage, their homemade rafts sank after just a few miles.

The train thieves and rafters were Coxeyites, and they were just two contingents of a nationwide movement calling itself Coxey’s Army. Taking the name of Jacob S. Coxey, an Ohio man who encouraged protestors from all over the country to converge on the nation’s capital, the so-called army’s cause was to draw attention to hard economic times and high unemployment that came with the economic crash of 1893. The hijackers had begun as a group of unemployed miners in Cripple Creek who decided that stealing a train was their only way of reaching Washington, DC and joining their fellow protestors. The Denver river-rafters similarly were made up of unemployed men that local authorities forced to go elsewhere—literally anywhere else as long as they were out of Denver—in search of economic redress.

While the protest movement was successful in drawing attention to the cause, labor tensions persisted long after the heist was over, leading to some of the most violent and shocking moments in Colorado history including the Ludlow Massacre. In many ways, the Coxey movement was a ground-up expression of discontent, and a precursor to various twentieth- and twenty-first-century protests of the unemployed and powerless, including the Occupy Wall Street movement of the early 2000s. Though the motivation may be familiar, their means were unusual, and were perhaps one of the most unique protest methods the state has ever seen.

The Gold King Mine near Cripple Creek, 1892.

Coxey’s Army

Colorado was facing particularly hard economic times following the Panic of 1893, a nationwide economic depression that was among the worst in US history. The silver market collapsed that year as a result of a national decision to demonetize silver and return to a currency based on gold, sending the state’s economy and its large silver mining industry into a nosedive.

One result was the rise of a statewide pro-labor, Populist movement. As distinguished from later political ideologies loosely dubbed as “populist,” the Populists of the late nineteenth century were a more-defined third political party movement. Its core constituency consisted of farmers, miners, and other laborers, who shared a distrust of corporations, banks, and the existing political structure. This Populist movement sought elective office by means of parties with a shifting set of names, but it was the People’s Party that enjoyed the most success in Colorado, culminating in the election of the state’s avowedly Populist eighth governor, Davis Waite, in 1893.

Growing tensions between miners and mine owners over poor working conditions were reaching a boiling point in many parts of the state, finally spilling over in Cripple Creek in February of 1894. Many unemployed silver miners had come seeking work in its gold mines. Although the local prevailing wage for miners had long been three dollars a day, the length of that work day varied from mine to mine, from eight hours to as many as ten. In early 1894, taking advantage of the confluence of an expanded labor pool and depressed economy, many of the mine owners collectively decided to establish a work day of a uniform nine hours, for no additional wage. Hundreds of miners promptly went on strike.

At around this same time, the continuing national economic depression and persisting high unemployment rate (probably well over ten percent) had sparked a different kind of response. On Easter morning in March of 1894, Ohio Populist Jacob Coxey set out with about 100 unemployed workers on a march to Washington, DC. The plan was to present Congress with Coxey’s plan to create a federally-funded roads project to put the unemployed to work building and improving infrastructure around the country. Because the marchers were organized along military lines, they were popularly referred to as Coxey’s Army, led by “General” Coxey. The official name of the movement, however, was the Commonweal of Christ.

Coxey’s march was extensively publicized and inspired a number of similar marching armies from all across the nation, particularly in the West, where organized labor and Populist followers provided ready recruits. In Cripple Creek, notices were posted around town stating: “All idle men are requested to meet at the flagpole, Sunday, April 23, 1894…for the purpose of forming a contingent for the Coxey industrial army.”

Three days later at the first meeting, “a recent arrival from the Pacific slope” addressed the crowd. This was John Sherman Sanders, a native of the Missouri Ozarks but more recently from either San Francisco or Spokane, where he was variously reported to have been either a miner, an engineer, or some type of electrician. At this first meeting, he was elected a “brigadier general” and would thereafter be identified with the honorific of General.

General Sanders quickly began drilling his volunteer recruits, and army-like rules were adopted, which included prohibitions of firearms, profane language, intoxicating liquors, fighting, quarreling, begging, and foraging. Although not reported locally at the time, some 500 Cripple Creek supporters joined in adopting Articles of Agreement, setting forth their “object and purpose” of a march to Washington, DC, to present demands for legislation aimed at addressing their dire economic straits. In addition to the familiar Populist demand for the return of federal support for silver coinage, this group proposed a bill for “irrigating millions of acres of desert land” in Colorado and other western states, “thus giving employment to thousands of now unemployed men and homes for thousands of families.”

On May 3 a brigade of 159 men left Cripple Creek for Washington, first marching seven miles to Victor, where they were joined by anywhere from fifty to 150 additional recruits. A short march to the mining town of Wilbur then brought the men to a brand new station of the Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad. In fact when they arrived, workers had just finished driving the last spike in the rail line. Railroad president William E. Johnson generously offered the free use of six rail cars to haul the men and their four wagons of baggage to Florence, east of Cañon City, making them the first passengers (of a sort) from that station.

Stealing a Train

At Florence, General Sanders formed five companies: three of Cripple Creek miners, one of Victor men, and one of Coal Creek miners from Florence. The Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad agreed to furnish ten empty box cars to transport the 354 men to Pueblo. They were met there by Pueblo Mayor L.B. Strait, who arranged for that town to feed three meals to all of Sanders’s men and to provide a Main Street parade, and attempted to negotiate free rail transportation further east. Missouri Pacific Railway officials, however, were adamant that transportation would be provided only at full fare.

Sanders, extremely unwisely in hindsight, told the Rio Grande’s superintendent that his army was going to Washington “if they had to steal a train from every road on the way.” Thus alerted, the Missouri Pacific officials therefore ordered all of their locomotives be sent east of Pueblo to prevent their capture by Sanders.

On May 8, after Mayor Strait told General Sanders that the city would no longer feed his men, the contingent’s officers met privately. Confirming the railroad’s suspicions, one of the companies then commandeered six Missouri Pacific coal cars in the Pueblo train yards and loaded them up with the camp’s equipment. Engineer P.G. Buerger was forcibly removed from idling Rio Grande switch engine No. 817, and was replaced by Morgan Cosgrove, a Coxeyite said to be a former Rio Grande engineer. With Sanders’s men controlling all of the rail yard’s switches, the fifty-ton engine was hooked up to the coal cars, the army’s men climbed on, and the train headed east out of town on the Missouri Pacific’s tracks.

Missouri Pacific officials, particularly Pueblo’s District Superintendent O.A. Derby, reacted by devising two plans. First, they ordered that another engine and some cars be “ditched” (or overturned) to block the track some fifty miles east of Pueblo, near Olney Springs. Second, they ordered that all water be removed from the tanks along the line east of Pueblo so that Sanders’s steam engine could not be replenished. And they obtained a warrant for the arrest of Sanders, his officers, and Engineer Cosgrove for the theft of a Rio Grande engine valued at eight thousand dollars, and requested an injunction restraining the movement of the “wild train.” It was noted that serving these court papers to the men in that train might prove a challenge.

Although initially reported as hurtling down the tracks at fifty miles per hour, the hijacked switch engine, ordinarily limited for use just within the train yards for switching cars from one track to another, was probably only capable of about twenty to twenty-five miles per hour at most. This is consistent with the fact that it took the Cripple Creek army two hours just to travel the thirty or so miles east from Pueblo to the town of Boone.

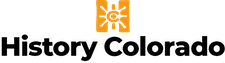

Shortly before midnight on the 8th, the army reached the “ditched” train, but the men, who had been erroneously warned that they were being trailed by a posse from Pueblo—(neither the railroad nor the Pueblo County Commissioners were willing to pay the expense) simply began building around it. They ripped up the tracks behind them, and re-laid them around the ditched train, all by hand, so as to bypass the obstruction. After just a few hours, they were back on their way eastward, but made only about ten miles before having to stop at Ordway to take on water for the engine’s steam boiler. The Missouri Pacific water tank there had been drained, but the water had puddled on the ground. One report had the undiscouraged Coxeyites using this puddle to fill up coffee pots and buckets to add to the boiler. A second, similar stop was made after another forty miles or so near Arlington, but the water in Adobe Creek there was so alkaline as to endanger the train’s boiler.

Another twenty miles or so brought them near Haswell, only to encounter a second engine and car ditched at the order of Superintendent Derby, requiring yet another impromptu re-laying of bypass tracks. Derby’s zealousness in this regard might have been partially due to antipathy toward the striking miners based on his own recent acquisition of an ownership interest in a local mine. With water again running low and impeding speed, it then took almost an hour to travel about fifteen miles and reach Eads. There, “a large number of men were set to work carrying [1,600 gallons of] water from a farmer’s well, a full quarter of a mile away.”

An illustration of Sanders’ Coxeyites carrying water via bucket-chain to refill their stolen engine’s boiler. While not widely remembered today, Sanders’ “wild train'' left quite an impact on the people of the time. This illustration was published three years after the Coxey marches, in a Memphis newspaper—one of many across the country to run a syndicated article about it that year.

With the engine’s water replenished, by the afternoon of May 9 General Sanders’s Cripple Creek “legionaries” had made it almost to the tiny town of Chivington (named after the infamous commander of the massacre at nearby Sand Creek), only to find yet a third deliberately-wrecked train, this one the most extensive yet. By now “wet with rain, worn out with exposure and hard work, with practically no food on hand,” the men called a temporary halt, and walked three or four miles into town “to get what victuals they could.” This only amounted to about “two potatoes, a small piece of meat…and a little coffee for each man.” And then it really started to rain on the camped-out men.

From here, accounts diverge. In one, Sanders somehow motivated the discouraged men and they returned to the ditch site and resumed efforts to once again bypass the obstruction. In the other account, a Missouri Pacific work crew arrived to clear the tracks for the mail trains, and were surprised when Sanders offered his men’s assistance.

This account is somewhat bolstered by ongoing judicial efforts. The railroad’s first attempt to obtain an injunction against the “wild train” crew had been filed in Colorado’s federal court in Denver. Federal Judge Moses Hallett, awakened at one o’clock in the morning to hear the request, denied it. The railroad had based its request on the stolen train’s supposed interference with trains delivering US mail, but Judge Hallett found that any interference was instead due to the railroad’s efforts to block its own tracks. The railroads then sought a judicial bypass, joining forces with the US Attorney in Kansas to seek judicial intervention in that state. Receiving some kind of assurance that the Kansas courts would be more helpful, Superintendent Derby ordered that one more ditched train in eastern Colorado be removed in order to clear the tracks into western Kansas, “where the little game will be stopped.” Sending a work crew to Chivington could well have been part of the plan to make sure the train was able to cross over into Kansas.

Losing Steam

Work on the tracks near Chivington was performed all through the night in a “driving rain,” and the tracks were cleared by 8 P.M. Water for the boiler was secured either from a nearby pond or by transporting barrels of water from Chivington in hand cars, and the train set out eastward at 9:00. General Sanders’s army next stopped at Sheridan Lake, where they expected supplies but received only a sack of flour and one loaf of bread. Their train then crossed the Colorado border and pulled into Horace, Kansas, where “the people from all the country around were there to greet the Industrials and gave them a rousing cheer.” The cheer was offset by the discovery that the “464 breakfasts which [Sanders’s army] had telegraphed for the night before at twelve cents each had been disposed of.” A Horace deputy sheriff arrested his own underaged brother, who had joined the army at Chivington.

The trip of 167 miles from Pueblo to Horace, overcoming the numerous railroad obstacles, was said to be “regarded by railroad men as little short of remarkable, for an engine of the [Rio Grande switch engine’s] class.” Perhaps for this reason, the men pulled off a remarkable switch themselves at Horace, and appropriated yet another engine, Missouri Pacific Passenger Engine 989 (“the best passenger train they could find”), to continue on east, Engineer Cosgrove again at the throttle.

Although Sanders and his men were said to have been confident of favorable treatment by Kansas’s own Populist governor, in fact their train was heading into a trap. Missouri Pacific officials were said to have obtained as many as 500 federal-court warrants for the arrest of Sanders’s army, and those officials had traveled in special rail cars to Scott City, Kansas, with a US Marshal and as many as 300 armed deputies on board.

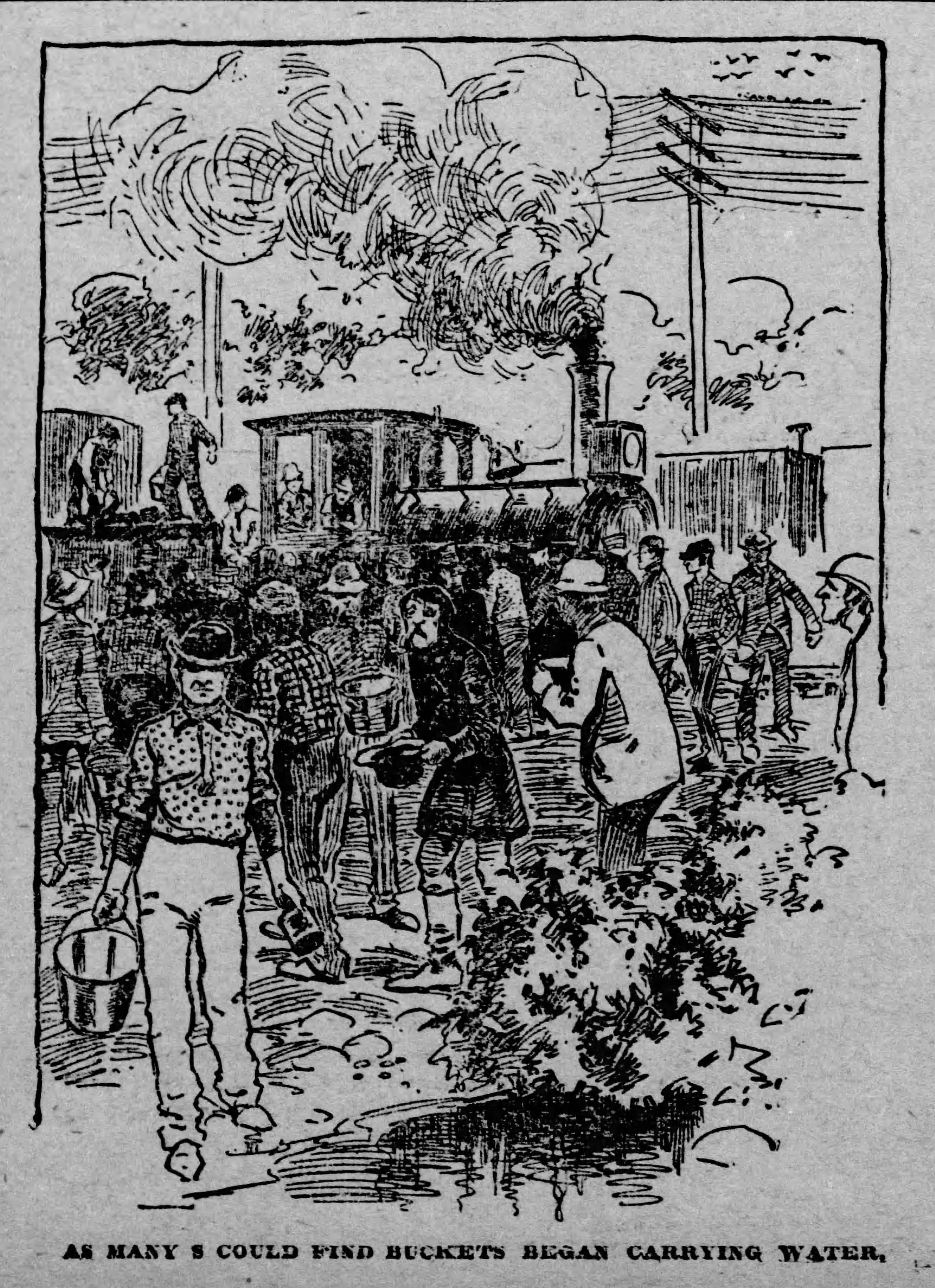

An illustration of “General” Sanders, made from a photograph taken of him while in Kansas. The theft of the train made headlines not just in Colorado and Kansas, but across the country.

Traveling some fifty miles from Horace, Sanders’s second stolen engine reached the Scott City trap on the afternoon of May 10. After some negotiations, food for his men, and dinner for Sanders in the railroad superintendent’s private car, Sanders announced an “unconditional surrender.” He was reported as saying to his 450 men: “Now, remember, boys, you are all under arrest as well as I,” with his men then yelling, “We will stay with you, general.”

Arrangements were made to return Sanders’s stolen Rio Grande switch engine to Pueblo, after determining that it had not sustained any damage. Found inside the cab when it reached Pueblo was a note from Cosgrove to Rio Grande engineer Buerger saying: “This is a good engine. Take good care of her. I may need her again.”

Considerably more damage had resulted from the railroad’s own efforts to obstruct the stolen train. Although not the most objective evaluator, General Sanders placed that damage at “fully $5,000.” He pointed out to a Missouri Pacific attorney that the railroad would have saved considerable money if it had only agreed to transport his men without charge as originally requested. An unidentified lawyer also claimed that the railroad had by then already incurred another eighteen thousand dollars in fees in responding to the “wild train.”

Sanders’s army of 450 men, now riding in passenger cars, were fed lunch (biscuits, boiled eggs, and coffee) in Hoisington, Kansas the next day, before being unloaded at Topeka, which proved only a temporary stop before they were transported to the army facilities at Fort Leavenworth. During this period, a story was sparsely circulated that among the recruits who had joined Sanders in Pueblo were two young women who had dressed in men’s clothing and were discovered only once at Leavenworth. The women were reported to be sisters, named Emeline and Leonore Gordon. Virtually all of the details in this account have defied verification. With the possible exception of two women, the demographic makeup of the army was said to include “a few Swedes, some Irish, possibly a dozen Scandinavians, two American-born Mexicans and two mulattoes.”

Trials and Small Fines

Detention at Fort Leavenworth continued for more than a month, until some sort of mass jury trial could be convened. On June 18, a federal jury delivered a verdict, somehow against a collection of 290 of Sanders’s men, finding them collectively guilty of obstructing US mail. This verdict did not apply to Sanders, who had been released on bond and was being charged in a separate case. Nor did it apply to his engineer, similarly released on bond. At the time of this mass trial, however, this engineer was being referred to as “William Lewelling,” even though all of the prior Colorado accounts had instead referred to Cosgrove. In any event, “Lewelling” did not make his required appearance on the day of that trial and was apparently never heard of again.

The following day, 121 of those convicted were sentenced en masse, each fined from between twenty-five and fifty dollars, and committed to jail for inability to pay those fines. They were distributed among five Kansas jails, ultimately “to be released in small numbers so as to effectually break up and disband the army.”

Sanders himself remained free, even marrying a woman in Leavenworth, but in mid-September ended up in the federal court in Wichita, where he pled guilty, possibly to mail obstruction as well, and was fined fifty dollars. A short stint in jail there ended when his “populist friends” paid his fine. Before the end of the month, he had returned to Colorado, saying he would campaign around the state for the Populist cause before that fall’s election. He said he had been traveling around the country “addressing audiences…as far East as Ohio,” but apparently had never made it to Washington, DC.

Any notion that his legal worries were behind him were ended just days after that fall election, when he was arrested in Pueblo on the warrant that had been issued way back when the train was first hijacked. Sanders’s plea that he had already been punished in Kansas for the transaction was unsuccessful, because this arrest was for seizure of Rio Grande property, not for mail obstruction. Sanders was released on bond, and returned in two weeks for the scheduled trial, only to learn that Rio Grande officials were not willing to see the prosecution proceed.

Although newspapers throughout the country had provided extensive coverage to the Pueblo train theft and its aftermath, the dismissal of charges represented the end of any significant publicity for Sanders, and little record of his later life remains. He did make it to Washington—but it was Washington state, where he lived before moving to California, dying at age sixty-nine or seventy in San Francisco on January 16, 1936. Nothing at all can be discovered of the fate of Cosgrove (or the mysterious Lewelling). The rest of Sanders’s army apparently scattered, with some of them no doubt returning to Cripple Creek. Upon returning, they would have discovered that they had missed out on the dramatic escalation of the miners’ strike they had left, culminating in late May with blown-up mines, and fatal encounters between strikers and more than a thousand “private deputies” hired by the mine owners.

Engine 817’s Engineer Buerger received one later newspaper mention, albeit posthumously. In 1900 he slipped underneath his own locomotive (Engine No. 621 this time) and was “ground to pieces.”

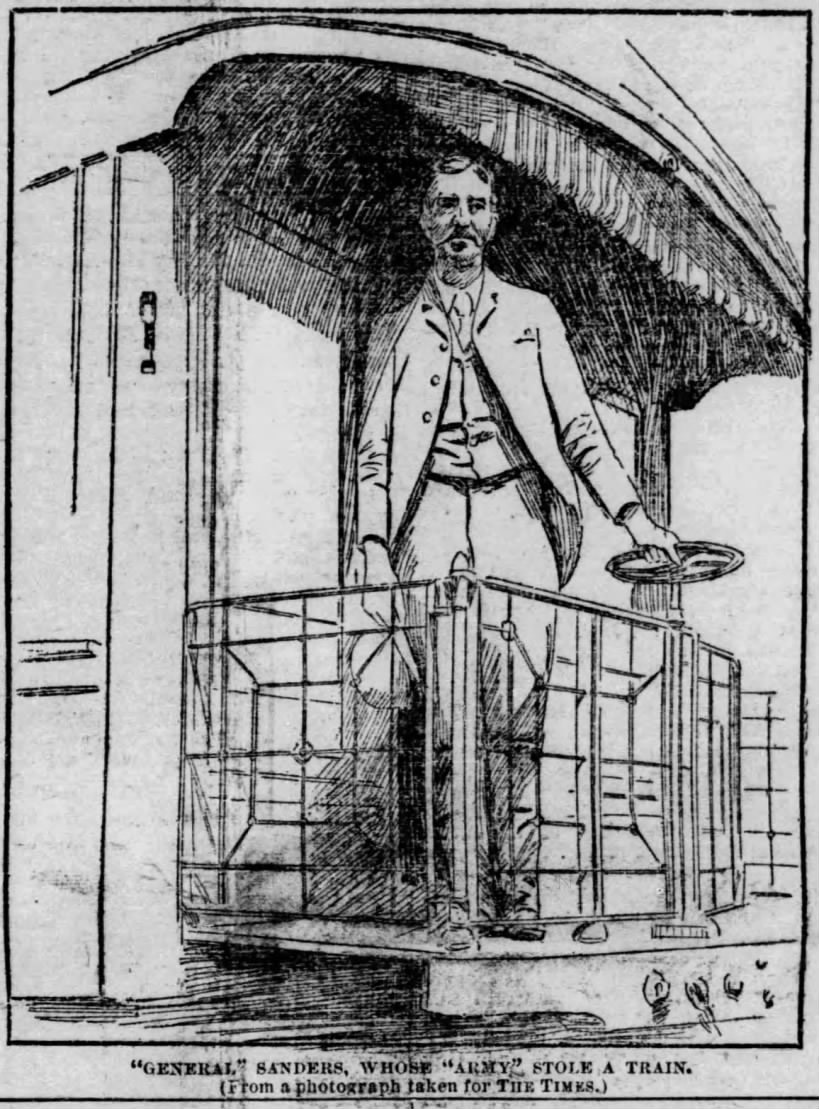

While the dramatic course of Sanders’s wild train ride was noteworthy because of how much distance was reached, it was not the only instance of Coxey’s followers “stealing” a train. In early 1894, trains were commandeered in Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Montana, and Wyoming, though generally no great distances were achieved.

Sanders’ Colorado contingent were not the only Coxeyites to steal a train. A group from Idaho made it all the way to Green River, Wyoming, with their stolen engine. This photo shows them being escorted onto a train back to Idaho by federal troops.

Coxey’s Navy on the Platte

The origins of Denver’s contingent of Coxeyites are somewhat different. As 1893’s depression progressed, Denver saw an influx of unemployed and homeless men. In the summer of 1893, they were gathered by the hundreds, housed in tents and fed in “Camp Relief” in the River Front Park west of downtown Denver along the Platte River. City officials ended the housing and food after several weeks, and instead offered free one-way rail tickets out of town.

In the spring of 1894, many homeless men returned to River Front Park, where they were joined by Coxeyites, many from California. “Before long, River Front Park had 1,500–1,800 residents, the largest encampment of Coxeyites in the country.” But the railroads were now not interested in providing free fare out of town. The Coxeyites’ elected leader, “General” William Grayson, publicly announced an effort to capture an empty freight train. After one such attempt was thwarted, Grayson ended up marching about one hundred of his men to Nebraska.

No doubt inspired by an account of another Coxey group in Montana trying to reach the East by boat down the Missouri River, someone in late May proposed having the Denver contingent head east down the Platte. That idea had actually been floated six weeks earlier, when an unnamed sailor from Scotland proposed travel to Missouri by raft, saying, “We will make the jags give us grub and grog and I will pilot yees safely over the blooming sand bars.” That proposal might have been somewhat sensible back in mid-April, when sand bars were still visible in the lazy Platte, but by early June conditions had changed dramatically. Colorado was deluged with heavy rainfall, resulting in significant flooding in Boulder and Pueblo. The Platte itself became an “alarming rampage” between Denver and Brighton, with a flow unmatched during the prior sixteen years.

Denverites had become anxious about the hundreds of hungry Coxeyites remaining in their midst. So, in spite of the raging floodwaters, the Denver Chamber of Commerce encouraged the homeless Coxeyites’ nautical departure by agreeing to provide lumber for constructing boats. On June 2, 22,600 board feet of lumber was delivered and hundreds of men began constructing 100 four-by-sixteen-foot flat-bottomed boats.

Coxey’s Navy in Denver, posing along the banks of the South Platte River with their flat-bottom boats. The boats have been painted with political slogans, such as “Down with Plutocracy” and “Crime.”

Although a trial run on June 6 resulted in two boats capsizing almost immediately, plans for the next day’s full-scale river excursion were not modified. On June 7, the entire Coxey’s Navy left Denver, planning to make Brighton the first stop on the way to Kansas City. Many of the first-time sailors didn’t make it that far.

Five boats never even made it farther than the equivalent of about ten city blocks, striking piers or capsizing even before reaching the bridge at 31st Street. For the remainder of the initial leg of the voyage, the next day’s Rocky Mountain News headlines tell the story:

“Only God will ever know how many of the Coxeyites were drowned in the Platte last night,’ said [Coxey Navy] Commander Twombley yesterday.” Only six bodies were ever recovered, with dozens more missing and suspected to have also drowned.

Accounts are somewhat confused about what happened to the survivors. Many apparently managed to travel, perhaps on foot, to LaSalle, south of Greeley. There are reports that they somehow managed to take a hijacked train from there to Julesburg, before unsuccessfully attempting to hijack yet another train there. About eighty men were arrested, returned to Denver and tried, with only five convicted and sentenced to short jail terms. And as a result, River Front Park was sealed off for good.

A Forgotten Fight

Summarizing the Coxey movement and its moment in American history, labor historian Carlos Schwantes provided an overall appraisal: “In common with the Populist revolt, Coxeyism was a democratic movement that called into question the underlying values of the new industrial society….The story of the Coxey movement is ultimately a case study of how ordinary citizens influence—or fail to influence—political and economic issues in modern America.”

In hindsight, the Coxey movement bore no direct fruits, either nationally or locally. The petitioned-for legislative reforms were not realized, although some would argue they were ahead of their time and were later more successful. Labor historians and progressives can also find parallels between 1894 and the present-day in their respective responses to the unemployed and unhoused. Lessons, too, can be learned from how a frequently unsympathetic local press responded to the Coxey protesters.

In Colorado, 1894 saw the peak influence of the local Populist movement. Both its incumbent Governor and Congressman lost their re-election bids that fall, and the People’s Party never again achieved statewide elective office. Still, Coxey’s Army proved somewhat of a model for later protest and petition movements, particularly the “Bonus Army” march on Washington for veterans’ benefits in 1932, and the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. But the overwhelmingly non-violent Coxeyites (Jacob Coxey’s own single conviction was for walking on the grass outside the US Capitol) should not be seen as the role models for the January 6 insurrectionists of 2021.

Though deadly serious for the unfortunate rafters from Denver who decided to navigate the Platte, the rest of Colorado’s Coxey contingent might seem like an amusing footnote in history. But to the diehard members of the movements, this was not just serious, it was a fight for their lives and livelihoods. To them, success meant the difference between a liveable wage and destitution. The circumstances driving them to these grand, dramatic efforts—a desperate economic downturn and the collapse of much of Colorado’s mining industry—show them to be one of the earliest expressions of the era’s growing labor movements that presaged much of the unrest and violence erupting in Colorado during the early decades of the next century.